In this week’s parasha, Mishpatim, the Torah prescribes capital punishment for a witch, stating that “A sorceress shall not live” (Exodus 22:17). Rashi explains here, citing the Talmud in Sanhedrin 67a, that although the phrasing is in the feminine, the law applies to a sorceress or a sorcerer. Both female witchcraft and male wizardry are forbidden. The reason that the Torah phrases it in the feminine is simply because sorcery is more common among women. The Zohar (I, 126b) explains why it is that women are more drawn to witchcraft than men:

It all goes back to the Garden of Eden, where the Serpent approached Eve and “injected into her a zuhama”, a spiritual impurity. Although this zuhama went on to “infect” all mankind that descend from Eve, women are more prone to its effects, and more drawn to the “Other Side”, the Sitra Achra. However, the Zohar also states elsewhere (such as in III, 230a, Ra’aya Mehemna) that women are more attracted to all faith in general, and it is easy to see how women today and throughout history were a lot more dedicated to their faith than men. Women are naturally more drawn to matters of faith, belief, and mysticism—whether good or bad.

Now, what actually constitutes witchcraft or sorcery? The Sages derive that there are 10 types of sorcery, based on Deuteronomy 18:10-11, which states “Let no one be found among you who consigns a son or daughter to the fire; or an enchanter who enchants, a soothsayer, a diviner, a sorcerer; one who casts spells, or one who consults ghosts or familiar spirits, or one who inquires of the dead.” The first in the list of ten is an “enchanter” (קסם), and then the term “who enchants” (קסמים) implies two more distinct types of enchantments. (In Modern Hebrew, this root term is used for a magician or illusionist.) Then we are given seven more practices.

A me’onen (מעונן) is one who predicts ominous times and seasons, from the root onah meaning a “season” or period of time. The same root here implies wasting seed, like Onan son of Judah in the Torah (Genesis 38). Thus, the Sages suggest that a me’onen is a person who performs sorcery using semen, or involving some other sexual perversion (see Sanhedrin 65b). Next comes a menachesh (מנחש) who “divines” and, literally, “guesses” the future through various means. For instance, in the Torah we read how Joseph would be menachesh using his special silver goblet (Genesis 44). The Talmud (ibid.) adds that a menachesh uses omens and derives meaning from all kinds of random events, or even from the activity of birds, fish, and other animals.

Then comes the mechashef (מכשף), this time phrased in the masculine, for a generic sorcerer. A chover (חבר) is translated as one who “casts spells” but that definition seems more fitting for the sorcerer. A literal reading of chover implies someone who connects and brings things together, lechaber, perhaps one who brews potions, reminiscent of a witch’s cauldron. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 65a) adds here that a chover is one who burns different concoctions of incense to idols or demons. The purpose may be to summon or gather those demons. Another possibility is that what a chover brings together is animals, for example snakes, scorpions, or insects. A chover, therefore, might include a malicious snake charmer.

The final three in the list of ten all seem to be about contacting ghosts and spirits. First is a person who inquires of ov (אוב). Based on the root, it may be a person who channels their dead ancestors (avot). Another is one who inquires of yidoni (ידעוני), translated as a “familiar spirit”, perhaps the ghost of someone famous and well-known like a great historical figure. The last is a medium who contacts the souls of the dead directly. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 65b) suggests that a person who practices ov may get possessed by a ghost and speak in their name. Often, this is done by the use of a skull. A yidoni, meanwhile, uses the bone of a certain animal called yadua to contact the dead. Finally, the generic “necromancer” is a person who fasts and then goes to sleep in a cemetery to collect information from dead spirits.

Biblical Warlocks

The Zohar (I, 166b) states that history’s greatest sorcerer was Laban, father-in-law of Jacob. In fact, when Jacob complains that Laban flipped his wages ten times, aseret monim (Genesis 31:7), the true meaning here is that Laban used all ten types of wizardry (outlined above) against Jacob! So, when Jacob later told Esau that he lived with Laban, im Lavan garti—that he lived with the infamous sorcerer and escaped his clutches—he meant to tell Esau that just as he escaped all forms of Laban’s sorcery, he would similarly withstand Esau.

The Zohar here says that the next great warlock of the Torah, Bila’am, learned his sorcery directly from Laban, who was actually his grandfather! The Talmud, meanwhile, has an opinion that Bila’am was one and the same person as Laban (Sanhedrin 105a). The Arizal reconciles the two by teaching that Bila’am was the reincarnation of Laban. Thus, he was both Laban’s descendant on the one hand, and at the same time literally Laban because he was his reincarnation (see Sha’ar HaPesukim on Balak).

The Tanakh (Joshua 13:22) actually calls Bila’am a kosem, the first type of sorcery on the Torah’s list. The verse here says that the Israelites killed Bila’am and his disciples el halaleyehem (אל חלליהם). The standard translation is something like “with their corpses”, but this reading doesn’t make much sense. The Zohar explains that halaleyehem really refers to their flying crafts, because Bila’ams team of sorcerers knew how to fly using magic! (In Modern Hebrew, a halalit is a spacecraft.) Today, flying on a broomstick is associated with witches. Where did this notion come from?

Talmudic Witches

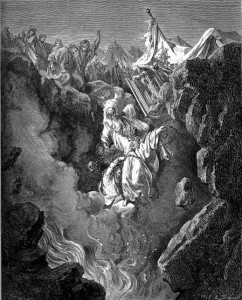

The only woman directly called a “witch” in Tanakh is Jezebel, the wife of the wicked Israelite king Ahab (II Kings 9:22). Jezebel is the one that relentlessly persecuted the prophet Eliyahu, but was ultimately defeated. The Talmud suggests that Ahab was such a wicked king only because he was bewitched by Jezebel (Yerushalmi Sanhedrin 10:2). Another Biblical figure thought of as a sorceress is the “Witch of Endor”, although she is not addressed this way in Tanakh (I Samuel 28). It was this necromancing woman that Saul went to in order to summon the soul of the prophet Samuel. The Tanakh makes sure to note there that Saul had previously banned all forms of necromancy, but when he himself needed the council of his now-deceased prophet Samuel, he hypocritically resorted to a ba’alat ov, a woman who practiced the ov form of necromancy.

Nikolai Ge’s “Witch of Endor” (1857)

The Talmud says much more about witches, and recounts multiple stories featuring them. In the most famous such incident, Shimon ben Shatach (early 1st century BCE), president of the Sanhedrin in his day (and brother of Queen Salome Alexandra), managed to execute eighty witches in Ashkelon at once. In fact, when he ran for president, Shimon ben Shatach’s campaign promise was that he would eliminate witchcraft from Israel. The Talmud says he initially failed to keep his promise, but when things got out of hand, he gathered a group of eighty men and headed to the cave in Ashkelon where the witches were headquartered. Through a clever ruse, he managed to capture all eighty of them, and had them all hanged.

The Talmud Yerushalmi mentions this in its exploration of the Mishnah (Sanhedrin 6:6) which teaches that it is forbidden to try two capital cases in one day. Yet, Shimon ben Shatach tried and hanged eighty. Presumably it was necessary in that situation, since the witches were highly dangerous and had to be eliminated immediately. The Talmud also mentions this story because the Mishnah presents an opinion that women were never hanged at all, only men were subject to hanging, yet here we have proof that Shimon hanged eighty women. Again, it was probably an exceptional case. (The Talmud Bavli also speaks about this incident briefly in Sanhedrin 45b).

In the Shimon ben Shatach story, the witches are able to conjure items at will, seemingly speaking them into existence. One conjured bread, another conjured a food, and a third produced wine. Some of the Sages were also described as being able to conjure, however not through black magic, but rather white magic, as taught in Sefer Yetzirah and other ancient mystical texts. Rav Oshaya and Rav Chanina had made a calf, while the sage Rava had bara gavra, produced a human-like golem (Sanhedrin 65b). Some say the magical incantation of “abracadabra” comes from Rava bara gavra, while others derive it directly from the Hebrew-Aramaic evra k’dibra, “I will create as I speak”. I have not heard a theory regarding the origins of the final word of the magical formula, “alakazam”, but my own conjecture is that it comes from al hakesem or al hakosem, through the powers of the kosem, the first of the Torah’s ten types of sorcery, the same term used to describe Bila’am.

As a general requirement, the Talmud teaches that a sage who sat on the Sanhedrin actually had to be knowledgeable in witchcraft and wizardry (Sanhedrin 17a). This is so that, like Shimon ben Shatach, the Sanhedrin would be able to properly apprehend and try witches and wizards. Relatedly, in Shabbat 81b we read how Rav Chisda and Rabbah bar Rav Huna were once on a ship and a witch wanted to sit with them but they refused, so she uttered a spell and the whole ship stopped in the middle of the sea! The rabbis uttered something of a counter-spell of their own, and the ship started moving again. The witch soon gave up, noting that the rabbis’ righteous conduct prevented her from harming them. In Pesachim 110a-b, the Sages teach a formula to recite in order to keep witches away, a lengthy phrase that includes statements like “may your hair fall out” and “may your spices scatter in the wind”.

Witchcraft Symbolism

The Zohar (II, 185a) explains that the Torah prescribes sacrificing a se’ir, a particular type of hairy goat, as a way to counter the powers of witchcraft. This is because the goat is a major symbol of witchcraft and sorcery. This symbol is often combined with a pentagram, a five-pointed star. The six-pointed star of Judaism, meanwhile, is something of a “one-up” over the pentagram, to subdue the wicked powers of the Other Side. It is interesting to point out that a se’ir goat was offered on Rosh Chodesh in particular, as a “sin offering” (Numbers 28:15). This was partly a sin offering for the sins of witchcraft, since Rosh Chodesh is considered a feminine holiday, traditionally observed more stringently by women, whose bodies similarly follow a lunar-like cycle.

An 1856 depiction of the goat-headed “Baphomet”, with the moon on the side and a prominent pentagram.

Modern-day “Wiccans” and witches still use the pentagram as their main symbol, as well as the goat-headed “Baphomet”, among others. And what of the classic image of a witch wearing a pointy hat, brewing in a cauldron, with a black cat, and a flying broomstick? Historians believe this image actually emerged in the 15th and 16th centuries as a smear campaign against women who had, until then, dominated the beer-brewing industry:

Since ancient times, it was women who made and sold beer. During the Protestant Reformation in Europe, this was discouraged and women were expected to stay home, while men should engage in business and go out to the marketplace. Women who brewed beer were depicted as witches, their cauldrons holding poisons and potions instead of beer. In those days, beer-brewing women did indeed have cats with them, to keep rats and mice from eating their grains, and they did wear long, pointy hats to be more visible in the marketplace. The broomstick, too, probably came out of a need to always sweep the dust and grain chaff in their breweries. Thus, its only in recent centuries that the image of a typical female beer-brewer—with cauldron, broomstick, cat, and pointy hat—turned into the image of a typical witch!

Finally, and most importantly, we must ask the big question: is witchcraft and wizardry actually real? Might it only be an illusion or a set of false beliefs and superstitions? Perhaps the effects of witchcraft are only placebo-like, and harm only those who believe in them? The Talmud and Zohar certainly make it seem like witchcraft and sorcery are real and potent. Yet, the great rationalist Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1138-1204) was among those who held that witchcraft is nonsense. He argued that the Torah forbids it not because it has real power, but because it is just meaningless, idolatrous drivel. One should stay away from any such beliefs or ideas. It is worth concluding with the Rambam’s eloquent words:

The masters of wisdom and those of perfect knowledge know with clear proof that all these crafts which the Torah forbade are not reflections of wisdom, but rather, emptiness and vanity which attracted the feeble-minded and caused them to abandon all the paths of truth. For these reasons, when the Torah warned against all these empty matters, it advised [Deuteronomy 18:13]: “Be of perfect faith with Hashem, your God.”

(Sefer HaMadda, Hilkhot Avodah Zarah 11:16)