Towards the end of this week’s parasha, Ki Tavo, we read a long list of horrifying curses with which God threatens the Jewish people if they stray from the path of righteousness. What’s more shocking than reading this terrible list is realizing that the Jewish people have experienced just about every one of these curses in our long history: oppression, destruction, injustice, fear, poverty, starvation, exile, genocide, desperation, forced conversion, captivity, expulsion, and utter annihilation. The Torah says that these travails will be so extensive that the Jewish people “will become an astonishment, an example, a byword among all the peoples to whom Hashem will lead you.” (Deut. 28:37) Israel will become the very epitome of curses and suffering. Indeed, history has confirmed this unfortunate prophecy.

Thankfully, the prophecies don’t end there. The haftarah for this parasha is a passage from the prophet Isaiah. Isaiah prophesies the very opposite, and says that a time will come when all of these curses will be reversed into blessings. Whereas Moses says God “will scatter you among all the nations, from one end of the earth to the other,” (28:64), Isaiah says that “all have gathered, they have come to you; your sons shall come from afar, and your daughters shall be raised…” (60:4). While Moses warns that “your skies above you will be copper, and the earth below you iron” (28:23), Isaiah says that “Instead of the copper I will bring gold, and instead of the iron I will bring silver.” (60:17) God confirms that He has put us through many trials in the past, and while this was long in duration, it was nonetheless only temporary, for “in My wrath I struck you, and in My grace I have had mercy on you.” (60:10)

Amazingly, we are living the fulfilment of Isaiah’s prophecies. The Jewish people have returned en masse to the Promised Land, have made the barren deserts bloom once more, and have miraculously defended their borders time and again. In the span of just several decades, the State of Israel has transformed into an agricultural, technological, and military powerhouse – despite very few natural resources, a small landmass, and a tiny population. As Isaiah predicted “…the abundance of the west shall be turned over to you, the wealth of the nations will come to you.” (60:5) Now, all that remains to be seen is the last part of Isaiah’s promises:

Violence shall no longer be heard in your land, neither robbery nor destruction within your borders, and you shall call your walls “salvation”, and your gates “praise”… And your people, all of them righteous, shall inherit the land forever, a scion of My planting, the work of My hands in which I will glory. The smallest shall become a thousand and the least a mighty nation; I am Hashem, in its time I will hasten it. (60:18, 21-22)

Israel will finally have true peace, with the world no longer questioning the indigenous Jewish people’s legitimacy to inhabit their Holy Land. The very last verse of this prophecy then says that when that time finally comes, God will “hasten” its arrival. This is quite the perplexing statement, and one that has kept rabbis and scholars thinking for millennia. The problem is as follows: If something is being hastened, then it is obviously coming before its time, and if it is coming on time, then it hasn’t been hastened!

Another way of looking at it is that one makes haste when they are already late. Few would disagree that this final redemption is long overdue. Since it is so late in coming, God will make haste to bring it about. An even simpler explanation is that when the time comes, God will hasten the series of events to bring about that happy ending. Recent history has shown that this is exactly what has happened.

In the late 1800s, the thought of an independent Jewish state in the Holy Land was still a very distant dream. The “first aliyah” began in 1882, and though as many as 35,000 Jews migrated to Israel by 1903, some scholars estimate that up to 90% of them left Israel soon after because of unfavourable conditions.

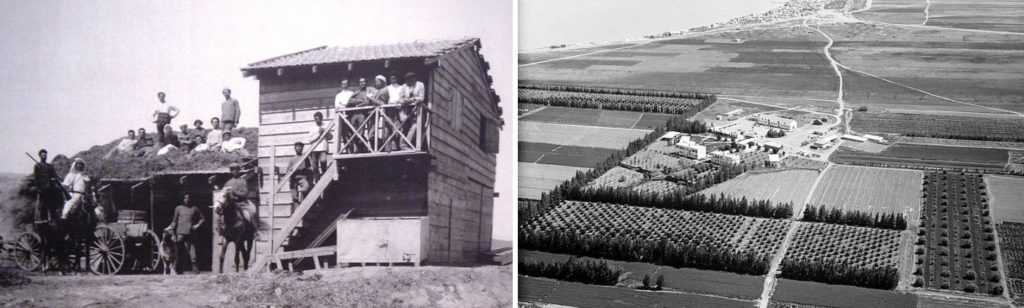

Then came 1909. In that year, a group of ten men and two women established a unique collective near the Galilee which would become the first kibbutz. The model of the kibbutz proved successful, and expanded from twelve people in 1909 to four thousand people living in thirty kibbutzim across the country by 1929. The kibbutz became one of the most significant factors in the rebirth of Israel, playing a key role in defending the land, driving agricultural innovation, and inspiring the “Israeli dream”.

Degania Alef, the first kibbutz, in 1910 (Left), and in 1931 (Right)

Around the same time in 1909, a group of 66 families parceled out a plot of land outside of Jaffa (which was previously purchased by a wealthy Dutch Jew named Jacobus Kann). By 1922, this little settlement had become the bustling city of Tel-Aviv, with a population hitting 34,000 just a few years later. It would only take two more decades for the declaration of independence to be proclaimed from that city, and two more to liberate all of Jerusalem.

66 Families Parcel Out Tel-Aviv in 1909 (Left); the city in 1922 (Centre); and Tel-Aviv today (Right)

Events have certainly progressed very quickly, and a glance at today’s geopolitical situation shows that they continue to rapidly accelerate. The spark for it all appears to have been lit in 1909 by those two seminal events – the first kibbutz and the first city – which propelled the rebirth of Israel and the fulfilment of Biblical prophecy. What’s most interesting is that this special number – 1909 – is precisely the gematria (numerical value) of that final cryptic verse of Isaiah: “The smallest shall become a thousand and the least a mighty nation; I am Hashem, in its time I will hasten it.”

The above is adapted from Garments of Light: 70 Illuminating Essays on the Weekly Torah Portion and Holidays. Click here to get the book!