This week we begin reading the third book of the Torah, Vayikra, called “Leviticus” in English because it mainly focuses on priestly laws and Temple services—facilitated by the tribe of Levi. We know that only a specific clan within the tribe of Levi, the descendants of Aaron, were the kohanim directly responsible for the offerings and rituals. The rest of the tribe of Levi had other tasks, including overseeing the refugee cities across the Holy Land, educational roles, supporting the kohanim, and serving as singers and musicians in the Temple. That last role was so significant that our Sages state a sacrifice that was brought without musical accompaniment was not valid!

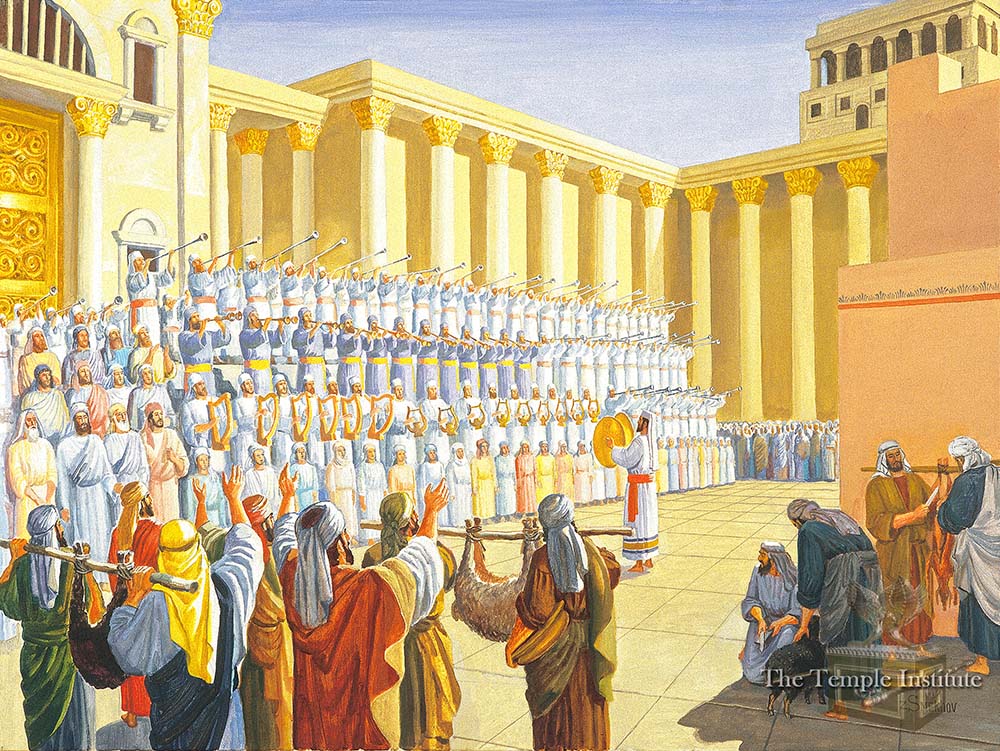

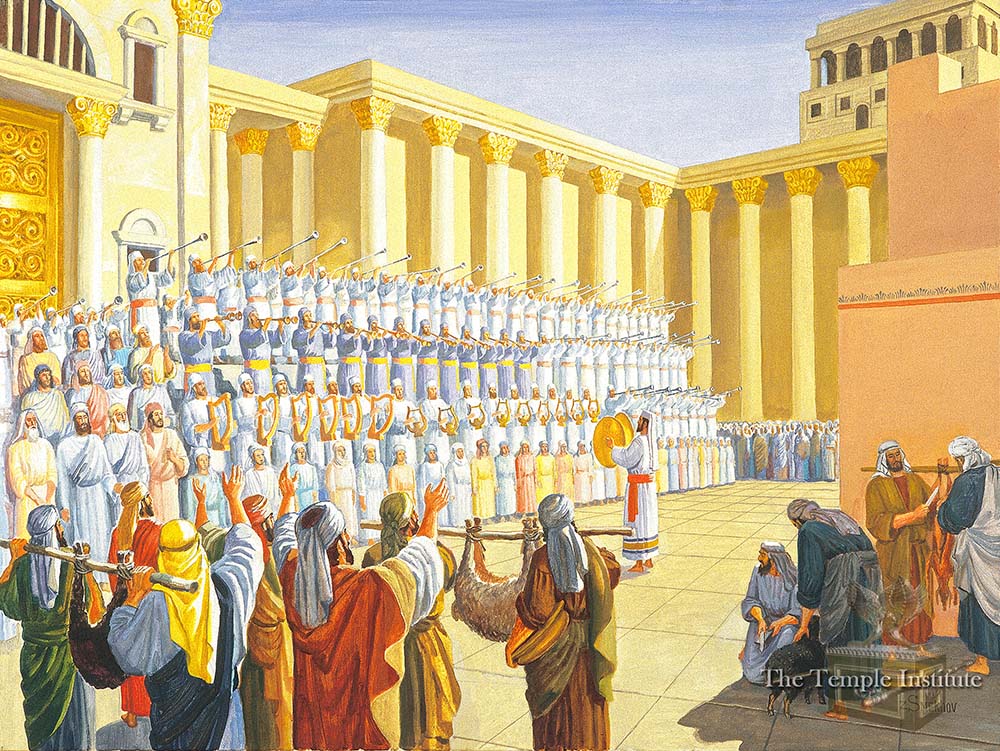

“The Levitical Choir” in the Temple, with harps, lyres, trumpets, flutes, and cymbals. (Credit: Temple Institute)

The Sages devote several pages to these matters in the little-known tractate Arakhin. The Mishnah (2:3) begins by describing the use of trumpets, lyres, and flutes in the Temple. It concludes by providing several opinions as to who were the main musicians, whether they were slaves, Israelites from the family of Pegarim and Tzippara or, of course, the Levites. The Talmud (10a) then goes into a discussion about which special days require recitation of Hallel, and suggests that in ancient times Hallel was musically accompanied by a flute, halil. The proof is Isaiah 30:29, which states: “For you shall be singing as on a night when a festival is hallowed; there shall be rejoicing as when they march with flutes, to come to the Mountain of God, to the Rock of Israel.” This teaches both that we must sing to God on a holiday (“when a festival is hallowed”)—as we indeed do through Hallel—and that it should be accompanied by flutes! Continue reading →