This week’s parasha, Shlach, ends with God’s command to the Israelites to put tzitzit on the corners of their clothes. The purpose of these strings is so that we should see them and “remember all of God’s laws” (Numbers 15:39). The Torah instructs that tzitzit must have a string of tekhelet, dyed blue. The Sages state that this blue represents the sea, which reflects the sky, which is likened to God’s Throne, which is described as being sapphire-blue, like tekhelet (Sotah 17a). At times, tekhelet is described as sapphire-blue or sea-blue, while other times it is described as greenish-blue or turquoise. Whatever the case, tekhelet is associated with the sea and its range of hues. The association here is actually quite mystical and profound. In fact, tzitzit is meant to remind us not only of God’s laws, but of Creation itself, and the very structure of the cosmos.

The first time that we see a greenish-blue string is right at the beginning, on Day One of Creation. We are told that at first, the cosmos was tohu v’vohu. These mysterious words have been explained in a wide variety of ways. The Talmud states that tohu and vohu were not just adjectives for “chaotic and void”, as typically translated, but rather distinct entities that were actually created. Rav Yehuda brings a teaching in the name of Rav that “Ten things were created the First Day, and they are: Heaven and Earth, tohu, vohu, light and darkness, wind and water, the measure of day and the measure of night.” (Chagigah 12a)

The Talmud then brings in another teaching to explain what tohu and vohu are: “Tohu is a green line that surrounds the whole world, from which darkness emerges.” Meanwhile, “Vohu are the spongy stones of the abyss from which emerge the waters.” The proof for this is a verse in Isaiah, which says: “and He shall stretch upon it the line of tohu and the stones of bohu.” (Isaiah 34:11) Amazingly, scientists drilling down beneath the Earth’s core up at the Kola Super Borehole discovered that, indeed, there are spongy stones beneath the surface which are full of water. In fact, scientists estimate that there is three times more water in these spongy stones than in all of the Earth’s oceans!

Scientists at the Kola Superdeep Borehole dug further and further into the Earth for decades, reaching a maximum depth of 12.2 kilometres in 1989.

Here we want to focus on the “green line” of tohu. While the word yarok is typically translated as “green”, Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Itzchaki, 1040-1105) says that yarok is tekhelet! (See, for instance, his comments on Exodus 25:4.) Thus, when the Sages teach that tohu is a kav yarok, they are really saying that the world is surrounded by a line of tekhelet. Sefer Yetzirah speaks of this line, too, and in his notes on the ancient text, Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan points out that mystical sources understood this line to be the horizon, which seems to subtly glow with a greenish-blue tinge (pg. 382). It is the tekhelet line that sailors see over the ocean horizon. This horizon line is the interface between light and darkness, day and night, hence the Sages’ statement that tohu is the line from which darkness emerges.

An image taken from the International Space Station on August 28, 2021 shows Earth’s atmospheric glow – could this be the tohu line that our Sages spoke of?

A time lapse showing the movement of stars over the course of the night.

While the Zohar describes the Earth as being spherical “like a ball” (Zohar III, 10a), Sefer Yetzirah associates the Earth with a galgal, a disk or wheel of some sort. The former describes the ball as spinning, while the latter suggests that it is the heavenly “dome” above the Earth that is spinning. That something is spinning is obvious from the fact that the stars above our heads clearly shift in circular fashion over the course of the night. Although the Zohar’s description fits neatly with modern science (incredible that it had this knowledge so many centuries ago!), we should not be so quick to discard Sefer Yetzirah, which offers some profound spiritual secrets and metaphors. Generally speaking, we find ancient rabbinic texts sometimes speak of the Earth as spherical and other times as flat. In the Talmud itself there is a mix of opinions, with some places clearly describing Earth as a ball (such as Avodah Zarah 41a) while others suggest a flatter shape (Chagigah 12b or Pesachim 94a-b).

The sixth chapter of Yetzirah begins by telling us that cosmos is made up of various components of threes. There are the three aspects of time, space, and soul (olam, shanah, nefesh); three primordial elements of fire, water, and air; and three major components to the Earth and Heavens: teli, galgal, and lev. One way to understand it is that the galgal is the “disk” of the Earth. The disk is suspended by a “string” connected to teli. Since Yetzirah is speaking here of constellations in the sky, many believe that the teli is the constellation Draco (the “Dragon”), which was seen in ancient times as being the pole around which the Heavens rotate. Millennia ago, a star in Draco (called Thuban) was aligned with the north pole and served as the official “North Star”, lending a further reason for why ancient peoples believed the Earth was suspended from Draco.

The sixth chapter of Yetzirah begins by telling us that cosmos is made up of various components of threes. There are the three aspects of time, space, and soul (olam, shanah, nefesh); three primordial elements of fire, water, and air; and three major components to the Earth and Heavens: teli, galgal, and lev. One way to understand it is that the galgal is the “disk” of the Earth. The disk is suspended by a “string” connected to teli. Since Yetzirah is speaking here of constellations in the sky, many believe that the teli is the constellation Draco (the “Dragon”), which was seen in ancient times as being the pole around which the Heavens rotate. Millennia ago, a star in Draco (called Thuban) was aligned with the north pole and served as the official “North Star”, lending a further reason for why ancient peoples believed the Earth was suspended from Draco.

Jewish texts, too, seem to mirror this notion. Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan points out that the etymology of teli might very well be talah, to “hang”, as if the Earth is hanging by a string attached to it. This is supported by various ancient sources cited by Rabbi Kaplan, including a Midrash that says Earth is suspended from a fin of the Leviathan. The teli was long-associated with the Leviathan (described as a dragon by our Sages), as well as the nachash bariah or “Pole Serpent” mentioned in Tanakh, as in Isaiah 27:1. (See “The Dragon, the Snake, and the Messiah” for lots more on the Leviathan and the Pole Serpent.)

The Ecliptic Line (גלגל המזלות) from a 1720 edition of ‘Tzurat haAretz’ by Rabbi Avraham bar Chiya (c. 1070-1145).

Another way to understand the galgal is that it refers not to the disk of the Earth, but rather to the galgal mazalot, the circle of Zodiacal constellations that appear to go around the Earth. This is called the “Ecliptic Line” and is related to the astronomical notion of a “Procession of the Equinoxes”. That this is the true galgal is supported by the subsequent verse in Sefer Yetzirah (6:2) which connects the galgal to the domain of time, not space. Thus, the galgal may be referring to the rotating “wheel” of constellations that seemingly goes around the Draco constellation teli which is above and centre. It would appear that the constellations “spin” around a stationary Earth over the course of time. (For more on the wheel of constellations and Procession of the Equinoxes, see the video series on ‘Astronomy & Astrology in Judaism‘.)

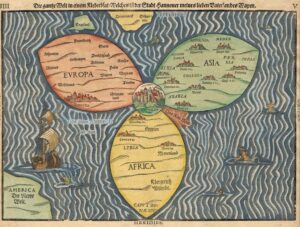

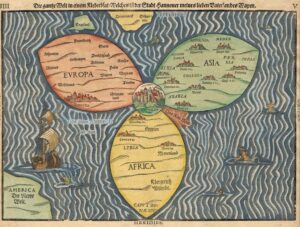

In olden days, maps were often drawn with Jerusalem at the centre of the world, like this one from 1581.

The third component presented by Sefer Yetzirah is the lev, literally “heart”. This might be the Earth itself, the “heart” and centre of the cosmos. More specifically, it’s the point at the centre of the Earth where the “string” from teli connects (and may refer to the actual “string” itself). Historically, that centrepoint was thought to be Israel, and specifically Jerusalem—and maybe that’s why it often seems like the whole world revolves around Israel and what’s happening over there. Fittingly, Ezekiel describes Israel as tabur ha’aretz, literally the “navel of the world” (Ezekiel 38:12), as if there is a cosmic umbilical cord attached to it.

So, we have a tekhelet string called tohu going all around the circular Earth, the horizon that separates light and dark. And we have the Earth suspended from an invisible “white” string tied to its centre, the lev. (One may interpret these verses to mean either the Heavens rotating around Earth, or the Earth itself spinning, as it “hangs” suspended from the Heavens.) These strings of Creation are reminiscent of the strings of tzitzit, and it is all the more interesting that the value of lev (לב) is 32, the total number of tzitzit strings hanging from the four corners. And although we generally speak of the four corners of tzitzit, the Torah’s language is a kanaf, literally a “wing”, and more accurately referring to the four compass points. The circular Earth has no corners, of course, but it does have the four cardinal directions. In these ways, the four “wings” of the tzitzit and their white and blue strings remind us of the spiritual makeup of the Earth and cosmos, of the tohu and the teli, the galgal and the lev.

Since tzitzit reminds us of Creation and of the unity of God, it is most fitting that our Sages included it within the Shema when we proclaim God’s unity. Better yet, the Mishnah that tells us when to recite the Shema in the morning says to do so from the moment one can “differentiate between tekhelet and white”, between the blue and white strings of the tzitzit (Berakhot 1:2). This is at dawn, when the tohu “string” around the horizon glows with tekhelet hues, as we move through another rotation of the galgal, hanging from the “string” tied to the teli of the Heavens. In reciting Shema, therefore, we connect to the spiritual foundations of Creation, and see the unity in all things, across the four compass directions, which our Sages teach are alluded to by the enlarged letter dalet of the word echad.

For more on the identity and meaning of tekhelet, see here.

The sixth chapter of Yetzirah begins by telling us that cosmos is made up of various components of threes. There are the three aspects of time, space, and soul (olam, shanah, nefesh); three primordial elements of fire, water, and air; and three major components to the Earth and Heavens: teli, galgal, and lev. One way to understand it is that the galgal is the “disk” of the Earth. The disk is suspended by a “string” connected to teli. Since Yetzirah is speaking here of constellations in the sky, many believe that the teli is the constellation Draco (the “Dragon”), which was seen in ancient times as being the pole around which the Heavens rotate. Millennia ago, a star in Draco (called Thuban) was aligned with the north pole and served as the official “North Star”, lending a further reason for why ancient peoples believed the Earth was suspended from Draco.

The sixth chapter of Yetzirah begins by telling us that cosmos is made up of various components of threes. There are the three aspects of time, space, and soul (olam, shanah, nefesh); three primordial elements of fire, water, and air; and three major components to the Earth and Heavens: teli, galgal, and lev. One way to understand it is that the galgal is the “disk” of the Earth. The disk is suspended by a “string” connected to teli. Since Yetzirah is speaking here of constellations in the sky, many believe that the teli is the constellation Draco (the “Dragon”), which was seen in ancient times as being the pole around which the Heavens rotate. Millennia ago, a star in Draco (called Thuban) was aligned with the north pole and served as the official “North Star”, lending a further reason for why ancient peoples believed the Earth was suspended from Draco.