In this week’s parasha, Yitro, we read the Ten Commandments. The Fifth Commandment is to honour one’s parents which, while certainly important, might seem like it doesn’t really belong in the “Top 10” biggest mitzvot. Can we really place honouring parents in the same category as the prohibitions of murder and adultery? Why is it so high up there?

One good explanation emerges when we consider honouring parents in relation to the Second Commandment: to have no other gods before Hashem, and not make any images or statues of idols. In ancient times, idolatry often went together with ancestor worship. In fact, there is evidence that the Canaanites used to worship their ancestors, alongside a pantheon of gods. So, perhaps the Torah meant to say: you must not have any gods before Hashem, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t honour your parents! Parents certainly shouldn’t be worshipped, but they should be treated with dignity and given an extra measure of respect.

Another explanation comes from a teaching of our Sages that there are three partners in the creation of a human being: father, mother, and God. The child-parent relationship is a mini-metaphor for the human-God relationship. If one cannot properly honour their parents, will they be able to properly honour God? And if one isn’t grateful for their parents bringing them into this world, they probably won’t be too grateful that God did, either.

Of course, some child-parent relationships are very strenuous, making it difficult for children to honour their parents in these cases. While there are definitely exceptions, the same can be said for the human-God relationship, which goes through rocky periods, too, resulting in people getting angry or upset at God for various trials and tribulations He sends their way. In short, developing our ability to appreciate our parents—even in conditions that are less than ideal—is good practice for developing the same approach to God, no matter what He throws our way. (It’s worth recalling Isaac Newton’s words that “Trials are medicines which our gracious and wise Physician gives because we need them; and the proportions, the frequency, and weight of them, to what the case requires. Let us trust His skill and thank Him for the prescription.”)

Going back to the Second Commandment, we are told not to make engravings or images of what “is in the Heavens above, or on the Earth below, or in the waters of the Earth.” (Exodus 20:4) This means it is prohibited to make images of any beings, whether celestial or biological (as animals were often worshipped in pagan religions). In fact, there’s been an issue of depicting lions upon the curtain covering the aron in the synagogue going back centuries. Some Ashkenazi authorities were lenient on this, especially if the image was a lion in profile, but most Sephardic authorities were stringent and forbid such images. This is especially the case in synagogues, since we don’t want it to appear as if people are praying towards these images. That said, we do know that several of the flags of the Twelve Tribes had animals depicted on them (such as the lion on Judah’s flag, the deer on Naftali’s flag, and the snake on Dan’s flag). So, outside of synagogues there isn’t necessarily an issue of having such images.

The biggest problem is depictions of human-like faces. The Ba’al haTurim (Rabbi Yakov ben Asher, 1269-1343) comments on the same Exodus verse above that the word temunah (תמונה), “image” has the exact numerical value (501) as partzuf adam (פרצוף אדם), “the face of a human”. Rabbi Ovadia of Sforno (c. 1470-1550) adds that you cannot make such an image “even if you do not mean to use it as an object of worship”! Ultimately, the Shulchan Arukh rules that it is forbidden to make human-like depictions only if the faces protrude, like in statues or embossed engravings (Yoreh De’ah 141). A flat image, like a painting or mural, is okay. The same should apply to photographs today.

Nonetheless, the problem with such likenesses is that they may indeed end up being used for idolatrous purposes, even though they were not produced with that intention. And unfortunately, this is precisely what has happened in some ultra-Orthodox circles today with regards to portraits of rabbis.

Pictures of Rabbis

Having a portrait of a great rabbi on the wall is undoubtedly a nice way to stay inspired and keep the valuable teachings of that rabbi in mind. That said, it is vital to remember that these are just photographs, and nothing else. Some in the ultra-Orthodox world seem to have forgotten this. My wife recently spoke to a woman who told her she doesn’t take off her wig at home because the rabbis hanging on the walls shouldn’t “see” her immodestly. While modesty is commendable, believing that images on a wall have some kind of awareness is not. Such a view is not only irrational, it may well be a complete transgression of the Second Commandment. (I haven’t forgotten the Talmud’s story of Kimchit, who declared that the walls of her house never saw her hair—but that was obviously a metaphorical expression, and not a literal belief in walls being conscious and having a sense of sight.)

Nowadays, one can get a portrait of the so-called “mouser rebbe” (at right), whose image can supposedly drive away mice infestations. The portrait is actually of the Hasidic rebbe Yeshaya “Shayale” Steiner of Kerestir, Hungary (1851-1925). The mouser rebbe “segulah” is really just avodah zarah, believing that a human image has some kind of spiritual or magical power. Besides, I highly doubt that Rabbi Steiner would have appreciated his face being used for pest control.

Nowadays, one can get a portrait of the so-called “mouser rebbe” (at right), whose image can supposedly drive away mice infestations. The portrait is actually of the Hasidic rebbe Yeshaya “Shayale” Steiner of Kerestir, Hungary (1851-1925). The mouser rebbe “segulah” is really just avodah zarah, believing that a human image has some kind of spiritual or magical power. Besides, I highly doubt that Rabbi Steiner would have appreciated his face being used for pest control.

A much more popular image is that of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, which is plastered just about everywhere nowadays. The Rebbe has become, by far, the most recognizable rabbinic face on the planet. When my wife was pregnant with our first child, a Lubavitcher friend gave her a keychain with the Rebbe’s photo on it, promising that it would help with an easy delivery. What is for some just a keychain has become for others a full-blown amulet! Indeed, for many within Chabad, images of the Rebbe have taken on a life of their own, and are deeply intertwined with promoting Chabad messianism (as explored in an interesting paper here).

Some have a picture of who they believe to be Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai on their walls. First of all, Rashbi lived nearly two millennia ago and there are, of course, no authentic representations of his face. (Some cite an absurd legend that because he was wanted by the Romans, they had a “mugshot” of him.) Second of all, Rashbi’s own Zohar says he was especially careful not to make any depictions whatsoever, in light of the Second Commandment (see, for instance, Tikkunei Zohar 121a). Even if the image is seemingly innocent and has no connection to idolatry, Rashbi warned it may eventually lead to idolatry anyway and cause people to falter and sin. Rashbi would certainly not be happy with the supposed “portraits” of him currently hanging on people’s walls.

The Zohar (I, 192a) does suggest that if one wants to better understand the teachings of their master, they can imagine their master’s face in their mind. It could just be that the Zohar is giving a tip or memory aid to help a person recall the teachings of their rabbi. Whatever the case, it has nothing to do with actually making physical depictions of the master’s face, which the Zohar would frown upon. The Zohar here uses Joseph as an example, saying that he would always imagine his father Jacob’s face, and this would inspire and motivate him to excel and succeed. Rabbi portraits should be just that: inspirational and motivational.

The fact that the Zohar connects the notion of “father” with the notion of “rabbi” is not coincidental. After all, the honour accorded to one’s rabbi is often compared to the honour accorded to one’s parent, and there is much discussion in Jewish law regarding who takes priority when it comes to the honour of one over the other. In some cases, like Joseph, a person’s father is their rabbi, too! Either way, we once again see a link between the Second Commandment and the Fifth Commandment.

Fake Portraits of Rabbis

Baal Shem of London, not the Baal Shem Tov

Rashbi’s face is not alone in the fake portrait department; there are numerous other “portraits” of rabbis which are not actually their portraits. The supposed picture of the Baal Shem Tov is actually the Baal Shem of London, Chaim Shmuel Yaakov Falk (1708-1782). He was also known as “Doctor Falckon” and was nearly burned at the stake for sorcery in Germany before fleeing to London! Worse still, the great Rabbi Yakov Emden accused him of being a Shabbatean! The Falk portrait was sketched by John Singleton Copley (1738-1815), a Christian artist famous for his portraits of various priests and dignitaries. Somehow, it became confused with the founder of Hasidism, probably because of the “Baal Shem” title.

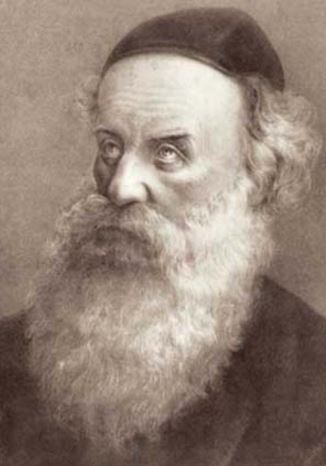

Apparently the Alter Rebbe

Meanwhile, the well-known “portrait” of the Alter Rebbe (Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, 1745-1812, founder of Chabad) was produced by Boris Schatz (1866-1932), who was only born some five decades after the Alter Rebbe passed away. Schatz was a friend of the Schneersohns. He claimed to have seen a true portrait of the Rebbe in the collection of a Polish count (called Tyszkiewicz in some sources). According to legend, the portrait was drawn by a soldier guarding the Alter Rebbe while he was imprisoned in 1798 (or 1796). Historians seriously doubt the credibility of any of these claims, though Chabad insists that the portrait is authentic. Schatz was primarily a sculptor (which is technically forbidden based on the Second Commandment), and served as the official court sculptor for Prince Ferdinand I of Bulgaria. He later become a prominent Zionist leader, and proposed the creation of a Jewish arts school at the Fifth Zionist Congress in 1905. The following year, he founded the Bezalel Academy of Arts in Jerusalem, still one of Israel’s preeminent art schools today. Schatz’s colleagues from Bezalel later said that Schatz had admitted the Alter Rebbe portrait was a forgery.

And what many people believe to be the Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1138-1204) was not the Rambam. For one, the man in the picture has his peyot shaved! (To fix the problem, modern renditions of the portrait add some artificial peyot, of course.) The current image is from the 1800s, based on an earlier work thought to be from the 15th century (see here). Supposedly, that image was based on an authentic engraving of the Rambam, but that’s unlikely considering the Rambam ruled such embossed engravings are forbidden (Mishneh Torah, Avodah Zarah 3:10-11), and the Rambam would not have had his peyot shaved. Some have proposed that the portrait of the Rambam is actually derived from an image of an Arab or Turkic scholar!

And what many people believe to be the Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1138-1204) was not the Rambam. For one, the man in the picture has his peyot shaved! (To fix the problem, modern renditions of the portrait add some artificial peyot, of course.) The current image is from the 1800s, based on an earlier work thought to be from the 15th century (see here). Supposedly, that image was based on an authentic engraving of the Rambam, but that’s unlikely considering the Rambam ruled such embossed engravings are forbidden (Mishneh Torah, Avodah Zarah 3:10-11), and the Rambam would not have had his peyot shaved. Some have proposed that the portrait of the Rambam is actually derived from an image of an Arab or Turkic scholar!

In short, to have images of rabbis for inspiration, motivation, or commemoration is totally fine. Anything more than that risks being idolatrous, and may well be a transgression of the Second Commandment. And, please, make sure the rabbi portraits you have are actually portraits of those rabbis!