The Passover Haggadah is one of the most ancient compilations of Jewish text. Its core goes back to the Mishnaic era (1st-2nd Century CE), and it came to its final version, more or less as we know it today, about 1000 years ago. The Sages filled the Haggadah with profound secrets and mysteries, giving people both young and old much to meditate and reflect on. In fact, we read in the Haggadah at the very beginning that although “we are all wise, discerning, sage, and knowledgeable in Torah”, it is still a mitzvah for each person to plunge into the Exodus story and uncover its secrets, and to share one’s thoughts and interpretations with others. Not surprisingly, the Sages embedded many such secrets and mysteries in the Haggadah itself. A small sample of them are presented below.

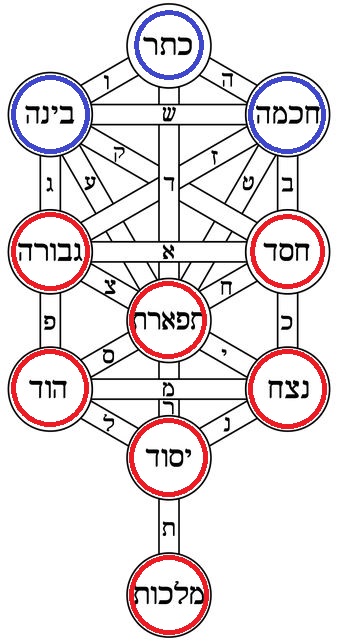

The Sefirot of Mochin above (in blue) and the Sefirot of the Middot below (in red) on the mystical “Tree of Life”.

The statement that we are all wise [chakhamim], discerning [nevonim], and knowledgeable [yodi’im], is a clear allusion to the upper three Sefirot of Chokhmah, Binah, and Da’at. The same verse also says we are all zkenim, literally “elders”, which is strange because obviously not everyone around the seder table is an elder! What does this really mean? We must remember that Da’at is only the inverse and the application of the highest Sefirah, Keter. There are, in fact, four mental faculties: Keter, Chokhmah, Binah, and Da’at, or willpower, information, understanding, and applied knowledge, respectively. (The Arizal actually teaches that these four are the reason the head tefillin has four compartments!) Now we can understand the purpose of inserting zkenim in the Haggadah: The highest Keter reflects the “face” of God known as Atik Yomin, the “Ancient of Days” (a term that comes from Daniel 7:22). This is the “elder” zaken in the Haggadah’s phrasing. All four mental faculties are stimulated at the seder, just as the tefillin stimulates all four.

The Haggadah continues by saying it is a mitzvah for us to lesaper, speak at length about the Exodus. Speech corresponds to the bottom of the Sefirot, Malkhut. And what of the six Sefirot in the middle? The Haggadah goes on to tell us that Rabbi Eliezer, Rabbi Yehoshua, Rabbi Elazar ben Azariah, Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Tarfon were all celebrating Pesach together one year. The teachings of these Mishnaic sages formed the core of the Haggadah text itself. They can be said to correspond to the six middle Sefirot (which are collectively called Zeir Anpin, and parallel the realm of Yetzirah, literally “formation”). You might ask: but wait, that’s only five rabbis—where is the sixth? The Haggadah itself answers: “Rabbi Elazar ben Azariah said to them: ‘Behold, I am like a man of seventy years, but I never merited to understand why the story of the Exodus is told at night until Ben Zoma expounded…’” The great Shimon ben Zoma is hiding here, too!

Recall that Ben Zoma is a contemporary and colleague of these wisemen, and even ascended up to the heavenly Pardes alongside Rabbi Akiva (Chagigah 14b). An amazing chiddush (that belongs to my wife) is that we can parallel the “Four Who Entered Pardes” with the Four Sons of the Haggadah: The wise one is undoubtedly Rabbi Akiva—the only one able to enter and exit Pardes in peace. The wicked one is, of course, Elisha ben Avuya who became the apostate Acher and traitorously joined the Romans. He totally separated himself from the Jewish community, so he said: “‘What is this service to you?’ To you and not to him.” The Passover service was no longer relevant to him. Hak’heh et shinav, Acher needed to have his teeth blunted! Then we have “the simple one” or “innocent” one, Ben Azzai, the bachelor who never married, and simply “gazed” at the Divine Presence only to immediately perish, his soul never returning back to Earth. Finally, the one who doesn’t know how to ask is Ben Zoma. Recall that upon his return from Pardes, Ben Zoma was thought to have gone “mad”, unable to converse with regular human beings or keep up a discussion with the Sages. Ben Zoma, quite literally, could no longer “ask”!

The Sages of the Haggadah were deeply contemplating the past redemption of Pesach, but also the future redemption of Mashiach. We find that much of the seder is centered around not ancient events, but forthcoming ones. This is, of course, evident from the concluding part of the seder with a wish for next year’s Pesach to be in a rebuilt Jerusalem, with a rebuilt Holy Temple, where we can properly bring a korban pesach. It is the deeper meaning behind reciting dam esh v’timrot ‘ashan, “blood, fire, and columns of smoke”—spilling a drop of wine for each—which actually comes from the prophet Joel’s vision of the End of Days (Joel 3:3). We are not talking here about the past miracles and plagues in Egypt, but the future signs and miracles that we await! The same goes for pouring a fifth cup for Eliyahu, with a prayer that Eliyahu returns speedily to usher in the Messianic Age. And this is the secret meaning behind those cryptic words we recite: sh’fokh hamatcha el hagoyim asher lo yeda’ukha! “Spill Your wrath upon the nations that don’t know you!” (Psalms 79:6)

Redemption & the War Against Rome

To fully understand the Haggadah, we have to keep in mind that its core was composed in the Mishnaic era, and the undisputed adversary and oppressor of the Jewish people at the time was the Roman Empire. In fact, Rabbi Akiva would end up being martyred at the hands of the Romans. And this connects to an incredible idea that has been proposed to explain that strange episode in the Haggadah where the five chief rabbis are getting together on Pesach. We must ask: why are the rabbis sitting together all night? Where are their families? The Torah commands that one must celebrate Pesach with family, and make sure to instruct one’s children and grandchildren. It seems here in the Haggadah that the five rabbis are alone, confined to a room until the morning when “their students came and said: the time for the morning Shema has arrived!” Even their own disciples were not with them at the seder. What’s going on?

We must remember that Rabbi Akiva’s generation lived at the time of the Bar Kochva Revolt. Rabbi Akiva himself supported Bar Kochva, and believed the latter to be the potential messiah of the generation:

Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai taught: “My rabbi, Akiva, used to expound that ‘A star shall emerge out of Jacob…’ [Numbers 24] is Bar Koziva… when Rabbi Akiva would see Bar Koziva, he would say: ‘He is the King Messiah!’ Rabbi Yochanan ben Torta would say to him: ‘Akiva, grasses will grow out of your cheeks and still the Son of David will not come!’” (Yerushalmi Ta’anit 24a)

Bar Kochva did indeed get very far in the war, managing to expel the Romans (albeit temporarily), re-establishing a sovereign Jewish state (and minting his own coins), even clearing the Temple Mount and starting to rebuild the Beit haMikdash. This would not have been possible without Rabbi Akiva’s support. Unfortunately, the war ended in disaster, with 24,000 of Rabbi Akiva’s students killed, along with Rabbi Akiva himself.

Coins minted by Bar Kochva

When exactly did Rabbi Akiva and his colleagues make the decision to support the revolt against Rome? This certainly would not have been an easy call to make. It would require all the chief rabbis of the time to get together and deliberate carefully. And, according to Rabbi Dr. Ronald Eisenberg (Essential Figures in the Talmud, pg. 16) this is precisely what they did on that Pesach night where they were all together. Confined in a room with no one else around, they stayed up all night to come to a verdict. The students arrived in the morning and said: Time’s up! Do we revolt or not? And what did the rabbis answer? They quoted that last part of the Haggadah: sh’fokh hamatcha el hagoyim asher lo yeda’ukha! “Spill Your wrath upon the nations that don’t know you!” This was the signal to go to war against Rome. And we do know that the main part of the war subsequently took place between Pesach and Shavuot (Yevamot 62b), which is why we still observe a mourning period during this time today. All the puzzle pieces add up neatly to explain this Haggadic mystery.

The Sh’fokh verse in the Darmstädter Haggadah (c 1430)

Bar Kochva wished to throw off the oppressive and idolatrous Roman yoke. In supporting him, the rabbis were hoping to usher in the Messianic Age. It was Nisan, the month of Redemption; and Pesach, the holiday of geulah. And those same Sages taught: b’nisan nigalu, u’b’nisan atidin liga’el, “In Nisan we were redeemed, and in Nisan we are destined to be redeemed again.” (Rosh Hashanah 11a) This was the maxim of Rabbi Yehoshua—the very same Rabbi Yehoshua of the Haggadah, sitting and deliberating with his colleagues all night on that fateful Pesach. It seemed the time was ripe for redemption. The Vilna Gaon taught (as relayed in Kol haTor) that Bar Kochva really was the potential messiah of the generation (otherwise, Rabbi Akiva surely would never have supported him!) Unfortunately, the potential wasn’t realized.

Nonetheless, that same potential exists in every generation, just as there is a potential messiah in every generation. The power to bring the Redemption is in our hands. It takes two things: proper Torah observance and true repentance on the one hand, as well as a collective “Mashiach mass-consciousness” on the other. Rabbi Akiva’s generation had the former, but not the latter. This is evident from the Yerushalmi passage above, where Rabbi Akiva was constantly declaring publicly that Bar Kochva was the messiah—to spread that “Mashiach mass-consciousness”—yet other rabbis were quashing people’s hopes and telling them to stop dreaming, as Rabbi Yochanan ben Torta did.

In this difficult time that we are currently in—where all of the prophecies have already been fulfilled and there are none left to await—let’s make sure we do both, and finally bring about the Geulah.

Wishing everyone a chag Pesach kasher v’sameach!