Vestments of the regular priest and the High Priest (Courtesy: Temple Institute)

This week’s parasha, Pekudei, summarizes all the components and items of the Mishkan. In the second aliyah, we read about the special ephod and choshen, the apron and breastplate of the kohen gadol. The choshen was studded with precious stones engraved with the names of the Tribes of Israel. Behind the choshen were placed the mysterious urim v’tumim. Through these, the Israelites were able to communicate with God. According to one understanding, the Israelites could ask questions, and God would respond by making the letters engraved on the stones light up.

The Zohar (II, 230a-b) on this week’s parasha connects the ephod, choshen, and urim v’tumim with tefillin. This is the secret of when God showed Moses “His back” but not “His face” (Exodus 33:23). On this, the Sages metaphorically state that God showed Moses the knot on the back of His tefillin (Berakhot 7a). Obviously, God does not literally wear tefillin, so the Zohar explains that it really serves to teach us the power of tefillin: Like the ephod, choshen, and urim v’tumim through which the Israelites could divine both past and future, tefillin can give a Jew the same power. The tefillin box that is on the front of the head is likened to the choshen on the front of the kohen, and represents looking ahead into the future. Meanwhile, the knot of the tefillin at the back (in the shape of a letter dalet) corresponds to the ephod covering the back of the kohen, representing the ability to understand the past. (The Zohar adds that the box on the front represents aspaklaria nahara, a “clear lens”, whereas the knot on the back is a murky lens.)

One explanation from our Sages about Moses being shown God’s “back” is that God showed him all of human history up to that point, so that Moses could see how God acted justly and righteously throughout. Everything that happened was brought about by God for a good reason, measure-for-measure. However, the reasons for future events, God’s “face”, were not revealed to Moses. This ties in to another teaching where Moses asked to see Rabbi Akiva and, while God granted him this request and transported Moses into Rabbi Akiva’s classroom, God did not reveal why Rabbi Akiva had to suffer a gruesome death (see ‘Time Travel in the Torah’).

A different explanation is that showing His “back” meant that God revealed to Moses everything from Creation forward (see Malbim on Exodus 33:23). What happened before Creation, God’s “face”, could not be revealed, for no human mind could possibly grasp this and live (Exodus 33:20). This implies that only after death, when the soul is no longer hindered by the body, could it grasp what happened before Creation. Our Sages taught that Moses attained 49 of the 50 Gates of Understanding, Nun Sha’arei Binah, while alive (see Rosh Hashanah 21b or Nedarim 38a). Only following death could he reach the 50th Gate. This is why Moses died on Mount Nebo (נבו), nun-bo, hinting that he finally had all nun levels of understanding “within him”, bo.

A four-pronged Shin on the head tefillin.

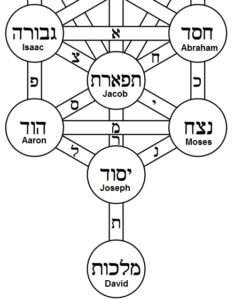

Putting it all together, we can see how the head tefillin gives us access to all Fifty Gates of Binah. There is a nice allusion to this in the two letters shin embossed on the box, one mysteriously having four prongs instead of three. The three prongs of a regular shin correspond to the Sefirot of Chessed, Gevurah, and Tiferet (see Sha’ar haPesukim on Shemot). The four prongs of the special shin are the remaining Netzach, Hod, Yesod, and Malkhut. This gives us all seven lower Sefirot from which the 50 Gates are derived: seven times seven (as we do during Sefirat haOmer), plus the fiftieth being Binah above. It is worth noting that elsewhere (III, 254a-b), the Zohar connects the seven prongs of the two tefillin shins—which are shaped like fire—to the seven branches of the Menorah.

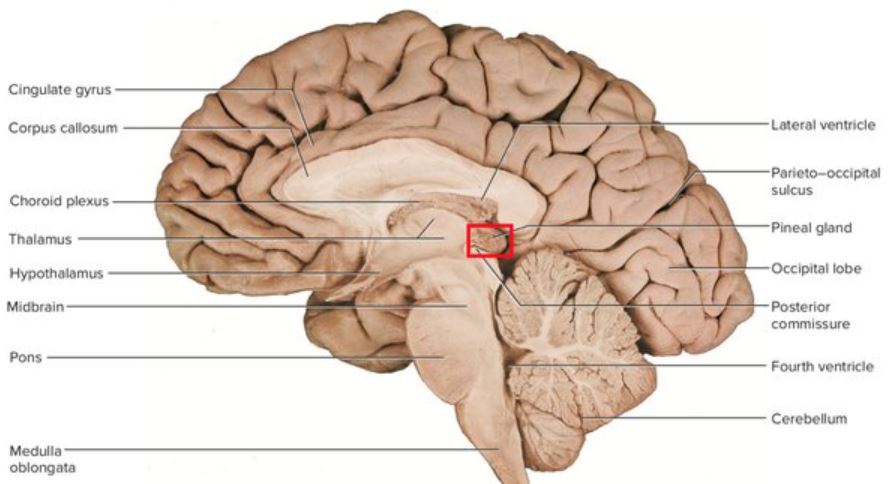

We see that the head tefillin is associated specifically with vision. Fittingly, the knot on the back aligns right with the occipital lobe of the brain, which is the visual processing centre. Meanwhile, the box of the tefillin “between the eyes” alludes to the inner “third eye” of the brain, the pineal gland, which bizarrely has photoreceptors like our eyes despite being deep inside the brain. The pineal gland regulates our sleep cycle and makes us dream, releasing a neurotransmitter called DMT which opens the mind up to all kinds of spiritual visions. (DMT is the active ingredient in Ayahuasca and used as both a therapeutic plant medicine and psychedelic drug. For more on the inner third eye in Judaism, see here.)

Based on the above, we can further understand why the Zohar says the box of the head tefillin represents clear vision while the knot at the back represents murky vision: the box (aligning with the pineal) is for tuning in to higher vision and prophecy, for spiritual vision; the knot at the back (aligning with the occipital lobe) is for regular physical vision. And this helps to explain why the box is associated with the future, while the knot is associated with the past. To get glimpses of what’s to come, we have to tap into our inner prophetic eye. But using our physical eyes we have the ability to look back in history and see God’s fingerprints all over the place. As Moses himself advised the people, if you want to find God, just “Remember the days of old, understand past generations…” (Deuteronomy 32:7) Jewish history—millennia of survival against all odds, and inexplicable success, influence, and prosperity at the same time—is perhaps the greatest proof for God’s existence. “Inquire now to the earliest days that came before you, from the day God created man on Earth, and from one end of Heaven to the other, has there ever been such a great thing? Or has anything like this ever been known?” (Deuteronomy 4:32)

So, the head tefillin takes care of past and future. And what of the present? For that we have the arm tefillin, bound specifically to the arm as a sign of action in the here and now, in this world of Asiyah. The arm tefillin is the present. In this way, our tefillin contain past, present, and future. Recall that the knot on the arm tefillin is in the shape of a letter yud, so altogether we have the shin on the head box, the dalet on the head knot, and the yud on the arm knot, spelling “Shaddai”. This is perfect because the divine name Shaddai embodies God’s presence throughout cyclical time—past, present, and future—and the value of “Shaddai” (שדי) is precisely 314, equal to the 3.14 of cyclical π (see here for more on ‘Secrets of Pi’). With this we come full circle, and get another reason for wrapping tefillin in circular fashion, around our heads, down our arms, hands, and fingers—the “Eternal Jew” binding past, present, and future into one.