This week’s parasha, Balak, recounts the attempt of two great sorcerers, Balak and Bilaam, to curse the people of Israel. Balak was a Moabite king who worried that Israel would conquer his land. He hired the famous gentile prophet and wizard Bilaam to curse the nation. Bilaam knew he would be unable to do this, for he can only pronounce what God desires. And so, each time Bilaam sought to pronounce a curse, a blessing emerged from his mouth instead. Balak tried several magical tricks and sacrificial rituals to change that, to no avail. Israel remained blessed.

The persistent motif in this parasha is the eye, or vision more broadly. Right from the beginning, we read:

Balak the son of Tzippor saw all that Israel had done to the Amorites… He sent messengers to Bilaam the son of Beor, to Pethor, which is by the river of the land of his people, to call for him, saying, “A people has come out of Egypt, and behold, they have covered the eye of the land, and they are stationed opposite me.” (Numbers 22:2-5)

This kind of language permeates the entire parasha, and is perhaps most concentrated in the following passage:

Bilaam raised his eyes and saw Israel dwelling according to its tribes, and the spirit of God rested upon him. He took up his parable and said, “The word of Bilaam the son of Beor and the word of the man with an open eye. The word of the one who hears God’s sayings, who sees the vision of the Almighty, fallen yet with open eyes. (Numbers 24:1-4)

Bilaam had a special “open eye” for seeing divine visions. Interestingly, although translated as “open eye”, the Hebrew is actually shtum or stum ‘ayin, which can be read as “closed eye”. Rashi comments on this dichotomy, bringing sources that favour both translations, with the possibility that Bilaam was blind in one eye or was missing an eye. The deeper mystical meaning is referring to an inner, spiritual eye. Aderet Eliyahu (the commentary of the Vilna Gaon, Rabbi Eliyahu of Vilnius, 1720-1797) states that this refers to seeing with divine inspiration. The Torah is alluding to an eye that is covered up, not visible on the face of a person. This eye is often referred to as the “third eye”.

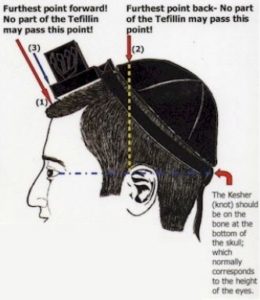

In Kabbalah, the third eye is associated with the head tefillin, which the Torah commands be placed “between your eyes”. Despite this, we do not put the tefillin between our eyes, but atop the head, above the hairline. This alludes to the fact that the head tefillin is about opening up our third eye, buried deeper in our brains. Science has shed some incredible light on this subject.

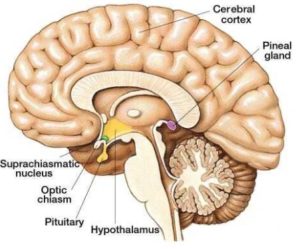

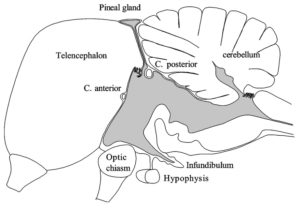

Deep in our brains is a small organ called the pineal gland. It releases the sleep hormone melatonin, and has also been found to contain DMT (dimethyltryptamine), a chemical that causes hallucinations and visions. Some say this chemical generates our dreams, or at least plays some role in dreaming. In South American shamanic rituals, a special tea (called Ayahuasca) with a high concentration of DMT is brewed and drunk in a religious ceremony to open one’s eyes to spiritual visions (and apparently works extremely well).

If we can point to any part of the brain as being a “receiver” for prophecy, it would certainly be the mysterious pineal gland. Most intriguingly, scientists have found that the pineal gland contains photoreceptor cells similar to those in our eyes! (In some animals, it rests higher in the brain and appears to respond to light, and may even be involved in processes like bird migration.) For these reasons, many have identified the pineal gland with the mystical third eye described in ancient mystical texts.

One of these ancient texts is the Zohar, on this week’s parasha. The section on Balak is among the longest in the entire Zohar. It includes what some identify as a separate mystical text that was only later incorporated into the Zohar, called the Yenuka, or “Child”. It describes a dialogue that Rabbi Yitzchak and Rabbi Yehuda had with a particularly precocious child. The child reveals some incredible mystical secrets, and one of these is regarding the inner eye. (For more on these secrets, and to the identity of this mysterious child, see the second edition of Mayim Achronim Chova – Secrets of the Last Waters.) The Zohar (III, 187a) reads:

[The Child] opened the discussion with the verse: “The wise man, his eyes are in his head, while the fool walks in darkness…” [Ecclesiastes 2:14] Why does it say the eyes are in his head? Are the eyes of a man in any other place? …Rather, the meaning of the verse is this: it has been taught that a man should not walk four cubits with an uncovered head. What is the reason? Since the Shekhinah rests upon the head, and a wise man’s thoughts and visions are in his head…

King Solomon alluded to the third eye when he said a wise man’s eyes are in his head and show him the light. The meaning of his words are quite clear, for he didn’t mean that a fool is literally blind, rather that he is lacking spiritual vision, which a wise man has. The Zohar comments by first stating that it is obvious the eyes are in (or on) the head. What one should understand is that contained within our heads are all of our holy thoughts and spiritual visions, imbued by God, and thus God’s divine presence, the Shekhinah, hovers over the head.

The Child goes on to state that a spiritual light emanates from the head of a righteous person, and he sees that light glowing upon the heads of Rabbi Yitzchak and Rabbi Yehuda. The Kabbalists associate that light with the two highest souls of a person, the Chayah and Yechidah. While the three lower souls (Nefesh, Ruach, Neshamah) reside in the body, the higher souls exude outwards and hover over the body. (For more on this, see A Mystical Map of Your Soul.) This is why it is common to wear two head-coverings, for example a kippah and a hat, which is meant to “cover” the two higher souls. These souls are particularly roused during prayer, which is the deeper reason for having a kippah and a tallit over one’s head.

The Child alludes to a Talmudic teaching of Rav Huna, who said he never walked four cubits with an uncovered head because the Shekhinah hovered over it (Kiddushin 31a). Elsewhere in the Talmud, we learn that an astrologer told the mother of Rav Nahman bar Yitzchak that he would become a thief, so his mother made him wear a head-covering his whole life to ensure “the fear of Heaven should always be upon him” (Shabbat 156b). It worked, and Rav Nahman became a great rabbi instead. Some cite this as the source for calling a kippah a yarmulke, meaning “fear of the King”. A kippah should remind a person at all times Who is above them.

Despite such teachings, wearing a kippah at all times was not a halachic requirement in those days. This was especially the case for an unmarried man, as we learn from another passage in the Talmud (Kiddushin 29b):

Rav Ḥisda would praise Rav Hamnuna to Rav Huna by saying that he is a great man. Rav Huna said to him: “When he comes to you, send him to me.” When Rav Hamnuna came before him, Rav Huna saw that he did not wear a head-covering. Rav Huna said to him: “What is the reason that you do not wear a head-covering?” Rav Hamnuna said to him: “The reason is that I am not married.” Rav Huna turned his face away from him, and he said to him: “See to it that you do not see my face until you marry.”

The story comes full circle with Rav Hamnuna. The Zohar states that the mysterious Child—who taught the secret of the inner eye and the kippah—is none other than the son of Rav Hamnuna Saba (“the Elder”). Although it isn’t entirely certain if these are the same Rav Hamnunas, it appears that this is indeed the case. Rav Huna (who was so careful with a head-covering) was the one who taught and made sure that Rav Hamnuna would get married and cover his head. The child that resulted from that marriage was the angelic child, who went on to reveal the secret of the head-covering.

It was Rabbi Yosef Karo (1488-1575), a great mystic in his own right, who incorporated this practice as law in the Shulchan Arukh, stating that one should not walk four cubits with his head uncovered (Orach Chaim 2:6). In previous centuries, wearing a kippah or head-covering was only mandatory during prayer (Mishneh Torah, Sefer Ahava, Hilkhot Tefilah 5:5). Even in the centuries following Rabbi Karo, there were those that maintained wearing a kippah at all times was not a strict requirement but a middat hassidut, an extra measure of piety. (Such was the view of the Chida, Rabbi Chaim Yosef David Azzulai, 1724-1806; as well as the Vilna Gaon, and Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch, 1808-1888).

Today, it has become accepted for a Jewish man to wear a kippah all the time, and for good reason. It is a mark of modesty, and a symbol of one’s Jewishness. It reminds a person of the Heavens above, and saves them from sin. It (hopefully) motivates a person to do Kiddush Hashem. It reminds a person of their higher souls, and the holy Shekhinah resting upon them. And it serves to stimulate and guard one’s “third eye”, one’s inner vision, and those holy Torah thoughts residing in the mind.

Pingback: Holy Cow: Parallels between Judaism and Hinduism | Mayim Achronim

Pingback: Debunking 6 Big Myths About Kabbalah | Mayim Achronim

Pingback: Judaism vs. Hinduism | Mayim Achronim

Pingback: The Mysterious (and Psychoactive) Ingredients of Ketoret | Mayim Achronim

Pingback: Why Kiddush on Wine? | Mayim Achronim