Over the course of Sukkot, we are graced with the spiritual presence of the “Seven Shepherds of Israel”: Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Aaron, Joseph, and David. These Heavenly guests are commonly known as the ushpizin. Interestingly, the root ushpiz or oshpiz, “guest”, actually comes from the Latin hospis, as in the English “hospitality”! What is the origin of the notion of Seven Shepherds? Where did the practice of inviting the ushpizin come from? And who are the mysterious “anti-ushpizin” that oppose the Seven Shepherds?

Origins of Ushpizin

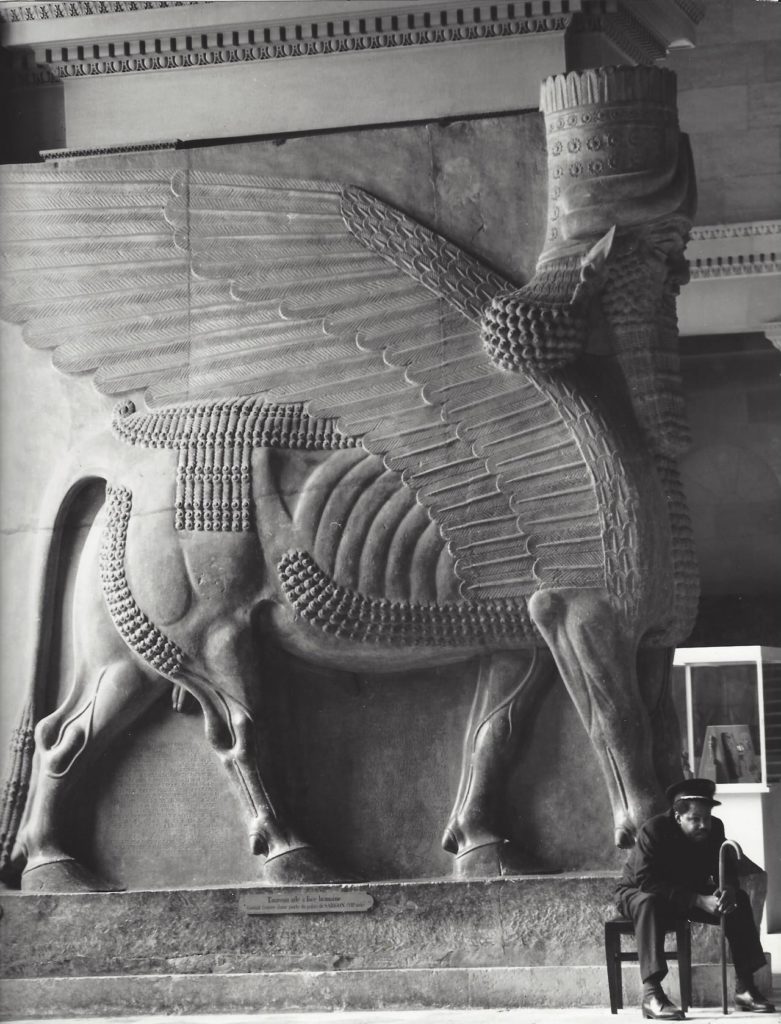

‘Micah Extorting the Israelites to Repentance’, by Gustave Doré

The idea of Seven Shepherds of Israel comes from the Tanakh, from the prophet Micah. The fifth chapter of his book begins by telling us that an ancient soul of Judah, mikedem mimei olam, will emerge out of Bethlehem of Efrat to be moshel b’Israel, a ruler of Israel. The next verse tells us it will come at a time of great desperation for Israel, following a series of “birth pangs”. This leader will be righteous, and serve in the name of God. We might think this is referring to Mashiach, but the chapter continues to warn that Assyria will invade and drive Israel into exile. It’s quite clear that Micah is speaking about the near future, and the Judean leader he envisions is the righteous Hezekiah, who drove away the Assyrian invasion and miraculously saved Jerusalem. Indeed, the Talmud (Sanhedrin 98b) records an opinion that all of the Messianic prophecies of the Tanakh were referring to Hezekiah!

Nonetheless, this chapter of Micah is seen as a “double-level” (or “dual-fulfilment”) prophecy, one that spoke of the near future in Micah’s own days, and also cryptically referred to a future time at the End of Days. This is how Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai read it, for instance, and saw “Assyria” here as secretly referring to Persia at the End of Days, who will invade Israel in the final apocalyptic war (Eichah Rabbah 1:41). Whatever the case, Micah 5:4 says that God will raise up “seven shepherds and eight princes of men” against the invaders. Again, the Midrash (Bamidbar Rabbah 14:1) wonders if this means there will be seven or eight messianic figures in the End of Days, and concludes that there will actually be four:

There is a great debate with regards to how many messiahs there will be. Some say there will be seven, as it is said “then shall we raise against him seven shepherds…” (Micah 5:4) And some say there will be eight, as it is said, “and eight princes of men.” And it is neither of these, but actually four, as it is said, “And the Lord showed me four craftsmen…” (Zechariah 2:3)

And David came to explain who these four craftsmen are [Psalms 60:9 and 108:9, where God declares: “Gilead is mine, Menashe is mine; Ephraim also is the defence of my head; Judah is my sceptre”]: “Gilead is mine” refers to Elijah, who is from the land of Gilead; “Menashe is mine” refers to the messiah who comes from the tribe of Menashe… “Ephraim is the defence of my head” refers to the Warrior Messiah who comes from Ephraim… “Judah is my sceptre” refers to the Great Redeemer, who is a descendant of David.

That said, the seven shepherds must refer to other figures. The Talmud (Sukkah 52b) explains: “Who are these seven shepherds? David is in the middle; Adam, Seth, and Methuselah are to his right; Abraham, Jacob, and Moses are to his left. And who are the eight princes among men? They are Yishai, Saul, Samuel, Amos, Zephaniah, Zedekiah, Mashiach, and Elijah.” The Sages seem to suggest that alongside Mashiach and Eliyahu, the souls of thirteen other great figures of the past come back to help them. Glaringly missing from the list of seven shepherds is Isaac. Why is he the only one of the Forefathers not included? Any why include Seth? Are there not greater figures of that era, like Noah and Enoch?

Some would explain Isaac’s omission from the shepherds by pointing out that, well, Isaac wasn’t really a shepherd! The Torah describes him digging wells and irrigating farms, his blessed crop producing me’ah she’arim, hundred-fold yields. A deeper explanation is given by the Arizal, who says that Itzhak (יצחק) is an anagram of ketz chai (קץ חי), “lives at the End”, as he will come back at the End of Days in the form of Mashiach ben Yosef, the “Warrior Messiah” mentioned above. The name Itzhak itself is in the future tense, meaning “he will laugh”—in the future when he is victorious in battle. The Arizal even proves it mathematically, as the value of Itzhak (יצחק) is 208, equal to Ben Yosef (בן יוסף)! (See Sha’ar haPesukim on Lech Lecha, for instance, and also the Ba’al haTurim on Deuteronomy 7:21.)

Noah was not a shepherd either, but a farmer. Enoch was a scribe and scholar, and transformed into an angel. That leaves Adam, Seth, and the longest-living Methuselah to represent the pre-Flood generations. Aaron was not a shepherd in Egypt, and served as high priest after the Exodus. Joseph was a shepherd-in-training in his teens, but did not return to that profession in Egypt. Instead, he oversaw all of Egypt’s farming operations and granaries. That leaves us with David, Abraham, Jacob, and Moses.

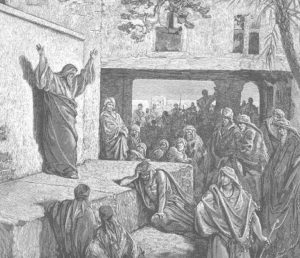

The lower 7 Sefirot correspond to the 7 Shepherds of Israel

The Zohar (III, 103b) comes in and tells us that holy figures of the past visit us on Sukkot, and this is the source for ushpizin. However, the Zohar only states “Abraham and five other tzadikim”, followed by another opinion that it’s “Abraham and five other tzadikim, plus David”. The Zohar doesn’t say who those five others are directly, but does quote Isaac and Jacob speaking. The whole passage itself comes from the mouth of Ra’aya Mehemna, the “Faithful Shepherd”, who is Moses. Right before this, Aaron is mentioned, for it was in his merit that the Clouds of Glory—which the sukkah is likened to—appeared in the Wilderness. The only one missing is Joseph. However, the Zohar always parallels such things to the Sefirot, and the six righteous figures are meant to correspond to the six Sefirot of Zeir Anpin, from Chessed to Yesod. The figure that always stands in for Yesod is Yosef haTzadik. David, meanwhile, is always paralleled to the seventh Sefirah of Malkhut. In this way, we find our Seven Shepherds, as we know them, in the Zohar.

The Anti-Ushpizin

Elsewhere, the Zohar (Sitrei Otiyot on Beresheet) says that the world endures in the merit of these Seven Shepherds of Israel. Opposing them are seven shepherds that stem from the “Left Side” or “Other Side”, the Sitra Achra. They seek to shepherd Israel away from God and towards idolatry. This is the meaning behind Jeremiah 15:9 which reads “She who bore seven is forlorn, utterly disconsolate; her sun has set while it is still day, she is shamed and humiliated. The remnant of them I will deliver to the sword, to the power of their enemies—declares God.” The Zohar lists the “anti-ushpizin”: Jeroboam, Ba’asha, Ahab, Yehu, Pekah, Menachem ben Gaddi, and Hoshea ben Elah. Who are these people?

Recall that Yerovam ben Nevat, “Jeroboam”, was the first king of the northern Kingdom of Israel after the split following King Solomon’s reign. Afraid to lose his throne and grip on power, he set up roadblocks so that his Israelites wouldn’t go to Jerusalem for the pilgrimage festivals. Instead, he built two idolatrous temples with golden calves. For this, the Sages say he has no share in the World to Come (Sanhedrin 10:2).

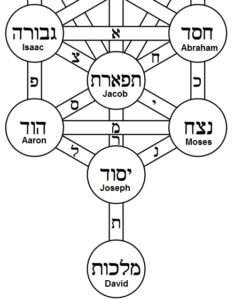

Ba’asha ben Achiya was the third king of Israel. He spent his reign at war with the Kingdom of Judah, and even allied with Aram at one point. He continued the wicked ways of Jeroboam, so God declared he would obliterate Ba’asha just as he did Jeroboam (I Kings 16:3). King Ahab is well-known, being the husband of the wicked idolatrous Queen Jezebel, and the tormenter of Eliyahu. His dynasty was destroyed by Yehu ben Nimshi, originally a military general. Yehu was used as an instrument by God to carry out Ahab’s punishment. However, Yehu went a step too far and bloodily massacred countless people in the Valley of Jezreel. Although God initially rewarded him with a multi-generational dynasty, He did declare that He would eliminate Yehu’s dynasty for the cruelty at Jezreel (Hosea 1:4). Amazingly, we have archaeological evidence clearly confirming Yehu and his story, from the Assyrian Black Obelisk.

King Yehu of Israel giving tribute to King Shalmaneser III of Assyria, on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III from Nimrud (circa 827 BC), currently in the British Museum.

Menachem ben Gaddi was another such general-turned-king. We know little about him. So was Pekah ben Remalyahu. He allied with King Rezin of Aram to attack Jerusalem. The Judeans were terrified, and it was in the context of this that Isaiah relayed his famous prophecy about the miraculous birth of a saviour child (Isaiah 7). Although it is abundantly clear that the passage is speaking about Hezekiah—who did go on to save Judea and Jerusalem as a young, righteous ruler—Christians infamously interpreted the prophecy to refer to the birth of Jesus (reading the word almah, a “young lady”, as “virgin”). Their argument that this, too, is a “double-level” or “dual-fulfilment” prophecy speaking about both contemporary times and future times cannot be the case. A double-level prophecy must not give a specific time, in order to allow interpretation for the present and the future. This prophecy clearly states the events are supposed to happen “in 65 years” (Isaiah 7:9). A specific time is given, leaving no ambiguity. The Tanakh continues to relay how the prophecy was fulfilled.

Pekah was assassinated by Hoshea ben Elah. The Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser III then appointed Hoshea as the new (and final) king of Israel. An Assyrian inscription confirms this, too, stating that the Israelites rebelled and “overthrew their king Pekah and I placed Hoshea as king over them. I received from them 10 talents of gold, 1,000 talents of silver as their [tri]bute and brought them to Assyria.” Hoshea didn’t last long. One of Tiglath-Pileser’s successors soon destroyed the northern Kingdom of Israel and exiled the tribes.

The souls of these seven idolatrous kings stand in opposition to the souls of the holy Seven Shepherds. We find that the Seven Shepherds of Israel were all about unity, bringing people together to serve God and inspire righteousness. The anti-shepherds, meanwhile, were power-hungry and vindictive, instigators of division and civil war, propagators of idolatry, and collaborators with Israel’s enemies. On Sukkot, we welcome in the spirit of the righteous ones as we bring people together in our huts. And we hope to expel the spirit of idolatry and divisiveness, of the wickedness stemming from “the Left Side”. This is all the more important to keep in mind and meditate on as we see what is happening all around us today in the Holy Land and the world at large.

Chag sameach!

More Sukkot learning resources:

Medicinal Properties of Arba Minim

Russia, Iran, and Gog u’Magog

What is Happiness?