In this week’s parasha, Bo, the Israelites are finally freed from their subjugation in Egypt. We read that in their haste to leave, they bound up their unleavened dough in their garments (Exodus 12:34). Intriguingly, the very next verse says that the Israelites took from the Egyptians “silver items, gold items, and garments”. This is significant in light of the famous Midrash that the Israelites merited to be saved because they preserved three things throughout their long enslavement: their cuisine, their language, and their clothing (see Pesikta Zutrata on Ki Tavo, 46a).* In other words, the Israelites preserved their unique Hebrew foods (included in which is observing the mitzvah of not consuming the gid hanashe, which began with Jacob), their divine Hebrew language, and also their unique mode of dress. What was this dress, and how was it different from the garments of the Egyptians?

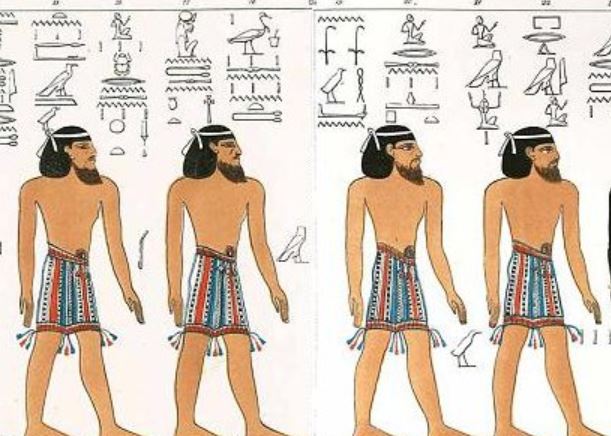

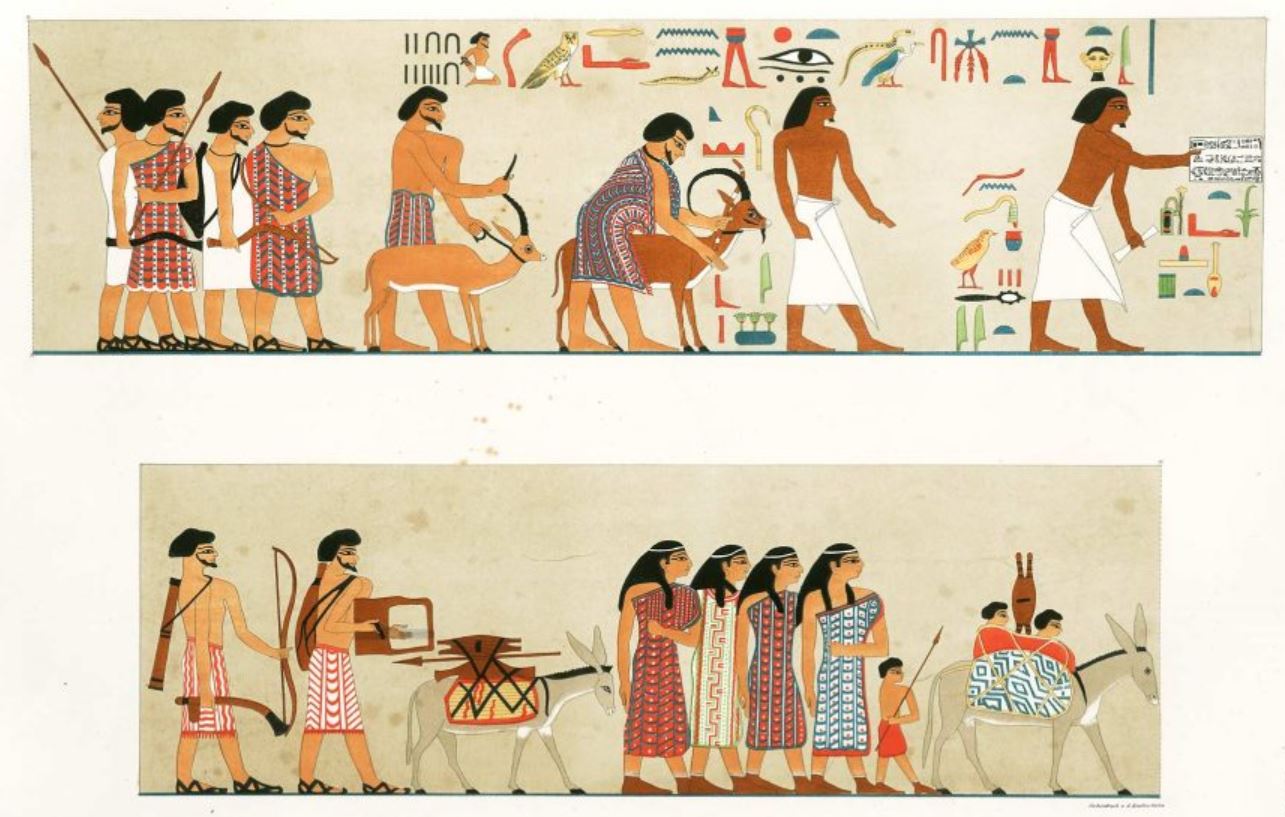

Egyptian tomb paintings at the Beni Hassan archaeological site depicting Semites migrating to Egypt.

Archaeologists have discovered many examples of ancient Egyptian work depicting immigrant Semitic peoples. One of the best preserved are the tomb paintings in Beni Hassan. Here we see the clear differences between the Israelite and Egyptian modes of dress. The Egyptians wear simple white skirts, and are clean-shaved except for some hair on the chin. The Semites, meanwhile, have longer multi-coloured and striped robes, together with fuller beards (see above).

A tour of the paintings at Beni Hassan:

Some scholars have connected these clothes to the famous striped or multi-coloured tunic of Joseph, the ketonet passim. In fact, archaeologists discovered a tomb complex in Avaris in northeastern Egypt—what was then Goshen, the region in which the Israelites dwelled—that has Semitic-style houses, together with twelve Semitic-style graves. One of the pyramid-like tombs has a large statue depicting a high-ranking official. Yet, he is not depicted in Egyptian garb, but with Semitic dress: multi-coloured and striped tunic, together with a shepherd’s stick. The evidence suggests that this tomb may indeed be the tomb of Joseph himself, and the remainder of the dozen graves there are for each of the twelve sons of Jacob!

A virtual tour of the amazing discovery of what might be Joseph’s tomb in Egypt:

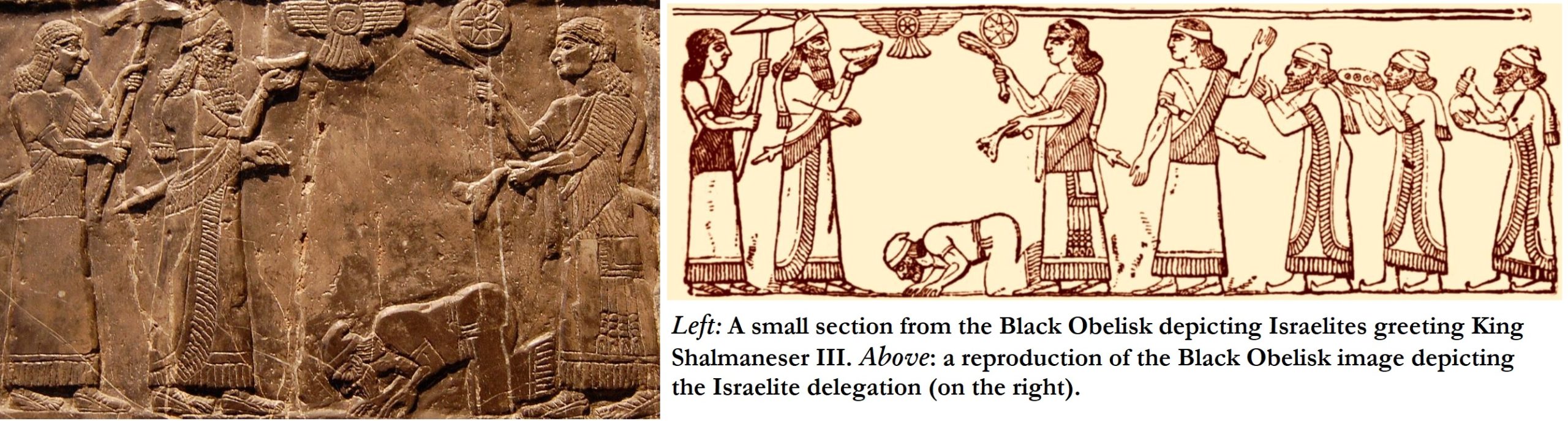

Jewish dress remained much the same in the centuries that followed. The Black Obelisk of the Assyrian King Shalmaneser III (c. 850 BCE) depicts Israelites (perhaps with King Yehu himself at the front) bearing similar long and striped tunics. It is most likely the case that such long and striped tunics gave rise to the tradition of having striped and coloured tallits that Jews still wear to this day. One key difference of note in the depictions on the Black Obelisk versus the previous ones is that now the Israelites always have their heads covered, too!  It was in the Middle Ages that Jewish dress became more varied. Some of this was due to the decrees of foreign rulers. Certain kings forced Jews to only wear black, others required special sashes to identify them as Jews, and in much of Medieval Europe, Jews had to wear distinct funky hats (including pointy ones or yellow ones).

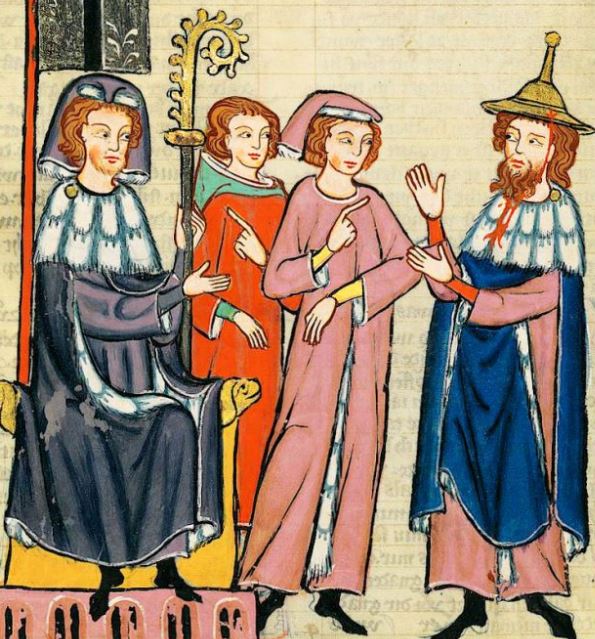

It was in the Middle Ages that Jewish dress became more varied. Some of this was due to the decrees of foreign rulers. Certain kings forced Jews to only wear black, others required special sashes to identify them as Jews, and in much of Medieval Europe, Jews had to wear distinct funky hats (including pointy ones or yellow ones).

A 14th century depiction of a famous German Jew named Suesskind of Trimberg (at right), from the Codex Manesse.

In the Sephardi and Mizrachi worlds, Jews often wore the same robes and headdresses as their gentile neighbours, including turbans in the west and dopushki in the east. Another type of headdress is the yarmulke, which some believe was inspired by the Turkic yağmurluk, “raincap”. (The Jewish etymology for it is, of course, yare malka, showing “fear of the King” or “fear of Heaven”.)

Interestingly, the ancient Greeks wore a round hat called a pileus, which the Romans minimized to something more of a skullcap. Christian priests would wear a similar zucchetto or solideo (still worn by the Pope and various bishops and cardinals today). In the 12th century, the Holy Roman Empire decreed that Jews must wear a special pileus cornutus to distinguish them. It may very well be that these headresses gave rise to what we know today as a kippah.

A Roman-style pileus on the left, and the red zuchetto of a Catholic cardinal, which is essentially indistinguishable from a kippah.

We see that, in general, Jews wore clothes similar to their neighbours. Even those ancient depictions of Israelites show attire like that of other Semitic and Canaanite groups. When the Russian Empire decreed in the 19th century that Jews must abandon their dress and adopt Russian dress, the Kotzker Rebbe (Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Kotzk, 1787-1859) didn’t protest because he argued there is no such thing as distinct “Jewish dress” anyway. Jews always wore clothes like everyone else, and Jewish attire varied by geographical location. Indeed, the dress that the Russians were referring to was simply the dress of the Polish nobility of the 16th and 17th centuries that was then adopted by Jews.

Those Eastern European shtreimels and kaftans are still worn by Hasidic groups today, but really bear no religious significance. They are simply cultural traditions, and have remained because rabbis in the 19th century, like the Chatam Sofer (Rabbi Moshe Schreiber, 1762-1839), ruled that anything “new is forbidden”, and whatever was the custom then was “frozen in time”, so to speak, and remains in force forever. (The main reason for such decrees was in response to perceived threats from the rise of both Reform Judaism and “Modern Orthodox” Judaism.)

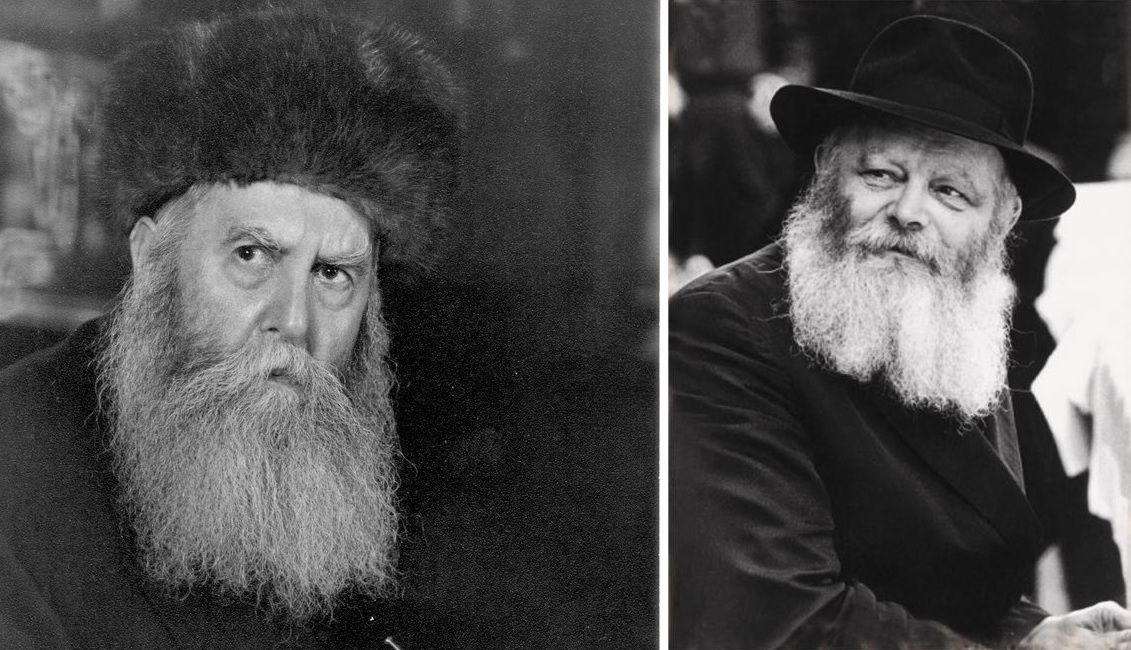

Rabbi Nosson Tzvi Finkel, the Alter of Slabodka

For Chabad Hasidim in particular, the Lubavitcher Rebbe did not wear a shtreimel like his predecessors, so Chabad switched to the fedora style more characteristic of non-Hasidim. This “yeshivish” style dates back to the Alter of Slabodka (Rabbi Nosson Tzvi Finkel, 1849-1927). At the time, yeshiva students were often impoverished and wore tattered clothes. His yeshiva would be different: he prioritized neatness and cleanliness, dignity and dressing in style. After all, one’s outer image was a reflection of their inner state! His students at the famed Slabodka Yeshiva in Lithuania wore suits and stylish modern hats, and even walked with canes, which was high fashion at the time. The style soon spread across the Litvish and non-Hasidic Orthodox world, and later to Lubavitchers in the second half of the last century.

Why the Lubavitcher Rebbe did not wear a shtreimel is a commonly-asked question, and several answers have been proposed, though ultimately no one knows for sure. I believe a big part of it has to do with the Rebbe wanting to be more “universal” in order to reach every single Jew out there. He was not the first to do this. For instance, the Yid HaKadosh (Rabbi Yakov Yitzchak Rabinowicz of Peshischa, 1766-1813) avoided Hasidic garb and wore regular peasants clothes because he wished to reach and connect to “every Jew in the marketplace”, to be relatable to everyone. As such, wearing distinguishing clothing might create an unnecessary barrier.

After all’s said and done, we find that the only garment that is truly uniquely Jewish is tzitzit (one might also add tefillin—though it is not quite a garment—first mentioned at the end of this week’s parasha). Tzitzit is the only specific identifying Jewish marker of dress across time and space, going all the way back to ancient Egypt: Incredibly, a unique relief discovered at the tomb of Seti I shows Semitic men with those characteristic striped and multi-coloured skirts, together with clear fringes attached at the corners—ancient tzitzit! We can learn from this yet again the tremendous importance of wearing tzitzit, a mitzvah that Jews have carried with them for centuries wherever they went, yet one that is often neglected today. (For more, see ‘The Secret Power of Tzitzit’ in Garments of Light, Volume Two.)

While we all dress differently today, a time will come when the differences may disappear. The Midrash (Beresheet Rabbah 95:1) states that at the Resurrection of the Dead in the End of Days, the righteous will come back to life looking like their old selves, with all their old blemishes, illnesses, and even the clothes that they wore (כְּשֵׁם שֶׁהוּא הוֹלֵךְ לָבוּשׁ כָּךְ הוּא בָּא לָבוּשׁ). The Midrash explains that this is so that the people will be recognizable as they were in their past lives, and also so that people can experience the power of God, for Hashem will then heal all the resurrected people and miraculously transform them back into healthy, youthful bodies. On a deeper level, we can derive from the Midrash that just as God will restore the bodies of all people to their pristine state, as the body was intended to be originally in the Garden of Eden, so too will He reclothe mankind with the primordial “garments of light” like the ones that first adorned Adam and Eve.

Shabbat Shalom!

*An alternate Midrash, in Vayikra Rabbah, says they were saved in the merit of four things: for retaining their names and their language, for not speaking lashon hara, and for staying modest.

From the Archives: How Long were the Israelites Really in Egypt?