At the start of this week’s parasha, Yitro, Moses’ eponymous father-in-law (aka. Jethro) joins the Israelite camp in the Sinai. The Zohar (II, 69b) explains, as per tradition, that Jethro wished to convert to Judaism, along with his entire family. The Zohar then uses this as a segue into a much broader discussion:

Rabbi Itzchak and Rabbi Yose were sitting one day in Tiberias and delving into Torah study. Rabbi Shimon passed by and asked: “What are you studying?” They replied: “We are on that verse from which our master taught us…” [Rabbi Shimon] asked: “And which is it?” They said: “That which is written: ‘This is the book of the generations of man [ze sefer toldot adam], when God created man, He made him in the likeness of God…’” (Genesis 5:1)

This verse in the Torah is used to introduce the genealogy of Adam and Eve. The Zohar explains that God showed Adam all future generations of humans that would descend from him, including all the future great leaders and sages (Jethro being one of them). Now, Adam was only given a vision of these people, meaning he only saw their outward appearance. Yet, from their outward appearance alone he could deduce a great deal about their souls. This is the deeper meaning behind sefer toldot adam, ie. wisdom that can reveal a person’s inner qualities, referring “to the secrets of the physical features of human beings… their hair, forehead, eyes, face, lips, lines on the hands, and ears. Through these seven traits a person can be known.” (Zohar II, 70b) The Zohar here is clearly referring to the ancient practices of physiognomy and chiromancy: understanding a person—and perhaps even telling their future—through their facial features and palm-lines.

The first question that immediately comes to mind is whether this would even be permitted in Judaism? After all, the Torah warns us not to “practice divination or soothsaying” (Leviticus 19:26), and these are two of the 613 commandments. We shouldn’t seek to predict the future; faith in God is all we need to carry us forward. (See also: ‘Should Jews Believe in Astrology?’) However, if a person seeks only to understand themselves, and figure out what they need to do to become better and more refined, that would not be a problem. Indeed, God wants us to self-reflect, repent, and refine ourselves.

Moreover, it is a foundational principle of Judaism that all things have a spiritual purpose, so the unique facial and chiral (ie. relating to the hand) features of a person must mean something. Surely it is no coincidence that each person has an absolutely unique set of fingerprints and handprints. God embedded this spiritual information on our physical bodies. The Zohar says this is one mystical meaning behind the Torah’s statement that God made us in His “image”. God has no physical image, of course, rather he imprinted various “images” upon our bodies which allude to all kinds of spiritual secrets.

The Zohar goes on to give numerous examples of what physical features might say about a person’s inner qualities. First it briefly discusses hair, and in most cases every hair feature has both positive and negative aspects. Hair is connected to the letter zayin. Then the Zohar discusses foreheads (metoposcopy), tied to the letter nun. For example, having a small, square forehead may be a sign of a person who “thinks he is wise, but knows little” and has an unsettled mind, while a small, rounded forehead is a sign of intelligence and kindness, though also a fearful disposition. Having three large wrinkles or ridges in the middle of the forehead is a good sign, and such a person will have success in Torah study. Four large ridges, however, is a sign that a person may be highly intelligent, and successful in Torah study, but for ulterior motives. Such a person may not be truly pious. A large, round forehead is a sign of wisdom and soft-heartedness.

The eyes relate primarily to the letter samekh. The Zohar talks about different iris colours, and the way the eyes appear. Then it goes into a lengthy exposition of the face, which ties into all 22 letters, followed by the lips and ears. These features, along with hair, were never very popular among the mystics. That is probably because the descriptions are somewhat vague and arbitrary, not to mention the simple fact that people passively inherit these traits from their parents! Metoposcopy (forehead-reading) was a little more popular, and it is said that the great Arizal (Rabbi Itzchak Luria, 1534-1572) was an expert in it. By far, the most extensive set of teachings relate to chiromancy, or palmistry. Scientifically-speaking, this is also most appropriate, since fingerprints and handprints (unlike facial features) really are unique to each person. Even identical twins, who have the exact same set of genes, have different prints!

An Introduction to Jewish Palm-Reading

The Zohar opens with the words “the hands of a man were under their wings” (Ezekiel 1:8). While these words come from Ezekiel’s description of the Divine Chariot, they also suggest that a person’s hands have some connection to the Heavens. Another verse from the Tanakh often used to support chiromancy is Job 37:7, which states “He inscribes the hand of every man, that all men whom He has made may know it.” This verse could certainly be taken to mean that God makes an imprint of a man’s life upon his hand.

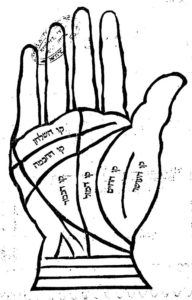

The Zohar (II, 76a) says that fingerprints and handprints connect to the letter kaf, which literally means “palm”. It then states that the lines of the hands correspond to the stars and constellations. In secular palmistry, too, the seven main lines of the palm are associated with the seven visible luminaries: the sun, moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. The Zohar’s descriptions of the lines are quite difficult to decipher. Thankfully, another text exists that clearly makes sense of Jewish chiromancy. The book is Shoshanat Yaakov, by Rabbi Yaakov ben Mordechai of Fulda (late 17th century). What follows is a brief summary from Shoshanat Yaakov, to serve only as an introduction to the major lines of the palm. Use the following image to guide you, taken from the 1706 Amsterdam publication of Shoshanat Yaakov.

The first line is called kav hachayim, the “life line”, and goes from the base of the thumb around to the side of the hand, below the index finger. If one has a clear, smooth, unbroken, pronounced life line from top to bottom, this is a sign of a long, healthy life. If the line is long, but broken along the way, this is a sign of possible health issues. Such a person should take stock of their health and institute preventative measures (for example, one whose diet is unbalanced shouldn’t delay making the proper changes to their eating habits).

The second line is called kav hachokhmah, the “wisdom line”, and begins where the life line ends—at the side of the hand between the thumb and index finger. It stretches across the palm. If the line is long and straight, going horizontally, this is a sign that a person is lacking in fear of Heaven and wisdom. On the other hand (no pun intended), if the wisdom line bends downward as it moves across the palm, and is thick and deep, this is a sign of being pious and wise. Such a person is also less likely to suffer from headaches. If the wisdom line is thin, shallow, and doesn’t stretch far, such a person is also lacking in wisdom, and may be prone to headaches. If the line is broken and faint, with abrupt stops, this portends possible mental issues or mental illness to come, God forbid.

The third line is kav hakavod, the “honour line”, stretching from the base of the palm up towards the pinky finger. This is a very important line and one who has a thick, clear, continuous honour line will have a good life overall, even if they are lacking in all their other lines. The honour line should stretch at least past the wisdom line for it to be a good sign. If the line has breaks, one can tell where they might have issues in life. For example, if the honour line has a break near the wisdom line, this suggests a person may have troubles relating to wisdom, or that they have an unsettled mind.

The fourth line is kav hashulchan, the “table line”, which begins beneath the pinky finger and stretches across to the other side of the palm, between the thumb and index finger. It runs above the wisdom line. If the table line splits into a fork at its end, this is a very good sign, and such a person has the potential for a lot of success and spiritual elevation. If the table line stops abruptly somewhere between the index and middle finger, near the base of the middle finger, this is a sign of an irritable, divisive, dominating person. Such a person may also be very “hot” and struggle with desires of infidelity.

If the table line stretches all the way across and touches the life line, this is a sign of a tricky, untrustworthy person. It is not a good sign either if the table line overlaps with the wisdom line. If the table line is faint or broken, such a person may have financial troubles, struggling to “put food on the table”. Conversely, if the table line is clear and deep, and has a nice breadth of space between it and the wisdom line, such a person will be financially secure and have a “king’s table”.

The fifth line is kav hamazal, the “fortune line”, going from the base of the palm up towards the base of the fingers. It is a good sign if the line is straight up, deep, wide, and unbroken. Some people have another line, kav ha’osher, the “prosperity line” inside the life line, on the “hill” of the thumb. This is a good sign for those who have the line. Another good sign is if a person has a clear shape of a triangle forming on the bottom half of the palm, especially from the base. Shoshanat Yaakov goes on to give many other signs, before switching into a discussion of foreheads, hair, eyes, nose, mouth, and even gait analysis.

In terms of which hand to use, the standard is to always use the right hand. Some say that the right hand should be used for a right-handed person, and the left for a left-handed person. Others say that the right hand should be used for men, and the left hand for women. A third idea (which I personally like) is that the left hand shows one’s potential, and the right hand shows one’s reality. With my own palms, I find that the left hand is nearly identical to the right, except that the lines on the left are generally more pronounced, clearer, longer, with less breaks. The only exception is the life line, which has a clear break on the left, but is smooth and full on the right. I hope that means I have made some good decisions which set my life line in order! (Meanwhile, the honour line is very faint on my right palm, but nice and clear on my left, suggesting I’ve got lots of work to do.)

The left-right/potential-actualization idea can actually help us make sense of palmistry, especially in light of the fact that we must not use it to predict the future. The truth is, palmistry is not so much about predicting the future as it is about recording, and reflecting on, the past. As a person goes through life, their palm lines will change. That means that the choices we make affect our lines—not the other way around! I believe this is the true meaning of ze sefer toldot adam, that a person’s hand is a chronicle of their past deeds. One can use the information engraved in their palms to better understand where they came from, as well as their flaws and strengths, in order to make better decisions for the future.

As the Talmud (Shabbat 156a) makes clear, our destiny is not written in stone; rather, we can write our own destiny through the choices we make. I believe this is why the wisdom of palmistry is discussed particularly in this week’s parasha, Yitro, which is all about a man who made one tremendously powerful, life-altering choice. He was an idolater of the highest calibre, a priest no less, but left it all behind to join God’s people, thus rewriting his entire destiny, to the point of being immortalized with a Torah parasha named after him, still recounted thousands of years later. Each of us writes our own story, and that vast record is incrementally etched into our palms. What do yours look like?