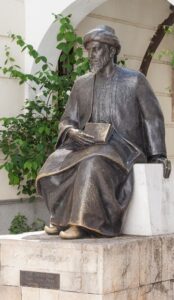

Rambam Monument in Cordoba, Spain

This Friday, the 20th of Tevet, is the yahrzeit of Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon (1138-1204), better known as the “Rambam”, or “Maimonides”. Rambam is one of the most fascinating figures in Jewish history, and also one of the most mysterious, multi-faceted, and complex. His impact on the course of Judaism cannot be overstated. Eight hundred years later, scholars, historians, and rabbis continue to debate his true views, positions, and beliefs. Rabbi Dr. Leon Stitskin (1911-1978), philosophy professor at Yeshiva University, described the Rambam as one who “reveals the truth by stating it, and hides it by contradicting it.” (Letters of Maimonides, pg. 18) More recently, Rabbi Dr. Aaron Adler (in his Al Kanfei Nesharim) noted a whopping 749 places where the Rambam’s early work, his Commentary on the Mishnah, appears to contradict his later works! And when it comes to the Rambam’s Moreh Nevukhim, the “Guide for the Perplexed”, some rabbis were so uncomfortable with it they denied that the Rambam ever wrote it! Who exactly was the Rambam, and what did he truly believe and teach?

Physician & Philosopher

Rambam was born in Cordoba, Spain to Rabbi Maimon, a student of Rabbi Yosef ibn Migash, who was a student of the famous Rif, Rabbi Isaac Alfasi (1013-1103). When he was around 10 years old, the extremist Almohads conquered Cordoba and forced all non-Muslims to convert, die, or flee. The Rambam’s family fled to North Africa. Settling in Morocco, the Rambam became a rabbi, but also studied at the University of Fez to become a physician. Meanwhile, he was deeply immersed in Greek philosophy, and came to embrace the school of Aristotle above the others. He is well-known for his work in integrating Aristotelian philosophy with Torah and Judaism. This set the stage for others around the world to do the same, most notably Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), a Catholic theologian and saint who integrated Aristotle with Catholicism, and cited Maimonides in his works. The Rambam believed that Aristotle was the greatest Gentile of all time, and wrote in his letter to Shmuel ibn Tibbon:

While the works of Plato, the teacher of Aristotle, are profound and substantive, one may apprehend their essential notions in other works, especially in those of Aristotle, whose writings embrace all philosophical concepts developed previously. For Aristotle reached the highest level of knowledge to which man can ascend, with the exception of one who experiences the emanation of the Divine Spirit, who can attain the degree of prophecy, above which there is no higher stage.

It wasn’t just Aristotle’s philosophy; the Rambam believed that the study of all natural science and philosophy was of utmost importance, writing to Yosef ibn Aknin that “as long as you are engaged in studying the mathematical sciences and logic, you belong to those who go around the palace in search of the gate. When you understand physics you have entered the hall, and when you master metaphysics you have entered the innermost palace.” So important was this that the Rambam even started his halakhic magnum opus, the Mishneh Torah, with the same advice. The Rambam arranged the Mishneh Torah around the 613 mitzvot, showing how all the halakhot fit directly under the framework of the Torah’s laws. Under the first mitzvahs of loving and fearing God, the Rambam wrote: “How does one come to love and fear God? When one studies His great and wondrous creations, one will see from these the wisdom of God—that it is immeasurable and unbounded—immediately he loves and praises and glorifies and has a great desire to know God.” (Hilkhot Yesodei HaTorah 2:2) It is the study of science and nature, of Creation itself, that will bring one to the true love and fear of Hashem.

In his late twenties, the Rambam began to write his first major work, the Commentary on the Mishnah. Before he finished it, he had to leave Morocco, and initially journeyed to Israel. He spent a little bit of time in Acre, and got to visit Jerusalem and go up the Temple Mount. (For more on the permissibility of ascending the Temple Mount, see here.) The date was the 6th of Cheshvan, which the Rambam henceforth established as a personal holiday for himself and his family. Living in Israel at the time, during the era of Crusades, was extremely difficult. And so, the Rambam ended up in Egypt, where he lived the rest of his life.

At first, the Rambam and his brother David ran a successful merchant business. Then, tragically, his brother drowned during a trade mission to India, taking most of the family’s wealth down with him. The Rambam would write of this time:

The greatest misfortune that has befallen me during my entire life—worse than anything else—was the demise of the saint [my brother], may his memory be blessed, who drowned in the Indian sea, carrying much money belonging to me, to him, and to others, and left with me a little daughter and a widow. On the day I received that terrible news I fell ill and remained in bed for about a year, suffering from a sore boil, fever, and depression, and was almost given up. About eight years have passed, but I am still mourning and unable to accept consolation. And how should I console myself? He grew up on my knees, he was my brother, he was my student.

With his wealth wiped out, the Rambam had to get a job to support himself, so he went back to medicine. His expertise, success, and fame as a physician spread, and he was eventually hired by Sultan Saladin’s chief secretary and advisor, Qadi al-Fadil. From there, Saladin himself took Rambam as his personal physician. The work was gruelling, and the Rambam wrote (in a letter to Shmuel ibn Tibbon):

My duties to the sultan are very heavy. I am obliged to visit him every day, early in the morning, and when he or any of his children or any of the inmates of his harem are indisposed, I dare not quit Cairo, but must stay during the greater part of the day in the palace. It also frequently happens that one of the two royal officers fall sick, and I must attend to their healing. Hence, as a rule, I leave for Cairo very early in the day, and even if nothing unusual happens, I do not return to Fustat until the afternoon. Then I am almost dying with hunger. . .

I find the antechamber filled with people, both Jews and Gentiles, nobles and common people, judges and bailiffs, friends and foes; a mixed multitude who await the time of my return. I dismount from my animal, wash my hands, go forth to my patients and entreat them to bear with me while I partake of some slight refreshment, the only meal I take in twentyfour hours. Then I go forth to attend to my patients, and write prescriptions and directions for their various ailments. Patients go in and out until nightfall, and sometimes even, I solemnly assure you, until two hours or more in the night. I converse with and prescribe for them while lying down from sheer fatigue; and when night falls I am so exhausted that I can scarcely speak.

In consequence of this, no Jew can have any private interview with me, except on the Sabbath. On that day the whole congregation, or at least the majority of the members, come to me after the morning service, when I instruct them as to their proceedings during the whole week; we study together a little until noon, when they depart. Some of them return, and read with me after the afternoon service until evening prayers. In this manner I spend that day.

It begs the question: why did the Rambam have to work so hard? Why did he not take a nice salary for being the chief rabbi? The Rambam ruled that it was totally forbidden to take money for rabbinic work or for Torah scholarship. Of this, he wrote (in Hilkhot Talmud Torah 3:10-11):

כָּל הַמֵּשִׂים עַל לִבּוֹ שֶׁיַּעֲסֹק בַּתּוֹרָה וְלֹא יַעֲשֶׂה מְלָאכָה וְיִתְפַּרְנֵס מִן הַצְּדָקָה הֲרֵי זֶה חִלֵּל אֶת הַשֵּׁם וּבִזָּה אֶת הַתּוֹרָה וְכִבָּה מֵאוֹר הַדָּת וְגָרַם רָעָה לְעַצְמוֹ וְנָטַל חַיָּיו מִן הָעוֹלָם הַבָּא. לְפִי שֶׁאָסוּר לֵהָנוֹת מִדִּבְרֵי תּוֹרָה בָּעוֹלָם הַזֶּה. אָמְרוּ חֲכָמִים (משנה אבות ד ה) “כָּל הַנֶּהֱנֶה מִדִּבְרֵי תּוֹרָה נָטַל חַיָּיו מִן הָעוֹלָם”. וְעוֹד צִוּוּ וְאָמְרוּ (משנה אבות ד ה) “אַל תַּעֲשֵׂם עֲטָרָה לְהִתְגַּדֵּל בָּהֶן וְלֹא קַרְדֹּם לַחְפֹּר בָּהֶן”. וְעוֹד צִוּוּ וְאָמְרוּ (משנה אבות א י) “אֱהֹב אֶת הַמְּלָאכָה וּשְׂנָא אֶת הָרַבָּנוּת”, (משנה אבות ב ב) “וְכָל תּוֹרָה שֶׁאֵין עִמָּהּ מְלָאכָה סוֹפָהּ בְּטֵלָה וְגוֹרֶרֶת עָוֹן”. וְסוֹף אָדָם זֶה שֶׁיְּהֵא מְלַסְטֵם אֶת הַבְּרִיּוֹת:

Anyone who comes to the conclusion that he should involve himself in Torah study without doing work and derive his livelihood from charity, desecrates [God’s] name, dishonours the Torah, extinguishes the light of faith, brings evil upon himself, and forfeits the life of the World to Come, for it is forbidden to derive benefit from the words of Torah in this world. Our Sages declared (Avot 4:5): “Whoever benefits from the words of Torah forfeits his life in the world.” Also, they commanded and declared (ibid.): “Do not make them a crown to magnify oneself, nor an axe to chop with.” Also, they commanded and declared (Avot 1:10): “Love work and despise Rabbinic positions.” And (Avot 2:2): “All Torah that is not accompanied by work will eventually be negated and lead to sin.” Ultimately, such a person will steal from others.

True Beliefs & Necessary Beliefs

Israeli commemorative stamp of the Rambam

Before his schedule got so hectic with work, in the 1170s and early 1180s, the Rambam had time to produce his two major masterpieces: first the Mishneh Torah, and then Moreh Nevukhim. Interestingly, he does not speak in these texts of the 13 Principles of Faith that he had enumerated earlier in his Commentary on the Mishnah. Thus, some scholars have argued that he abandoned his insistence on these 13 Principles. (Later, Rabbi Yosef Albo [c. 1380-1444] would write his Sefer HaIkkarim to prove that Judaism really only has three fundamental principles of faith, the others being secondary.) There are hundreds of more cases where the early Commentary seems to contradict the later works. Even the Mishneh Torah and Moreh Nevukhim (“the Guide”) have apparent contradictions between them. One famous example is regarding sacrifices. In the former halakhic code, the Rambam writes in detail about how the sacrificial procedures that were once carried out in the Jerusalem Temples will all return with the forthcoming Third Temple. But in his philosophical Guide (III, 32), he suggests something entirely different, writing:

It is impossible to go suddenly from one extreme to the other: it is therefore according to the nature of man impossible for him suddenly to discontinue everything to which he has been accustomed. Now God sent Moses to make [the Israelites] a kingdom of priests and a holy nation (Exodus 19:6) by means of the knowledge of God… But the custom which was in those days general among all men, and the general mode of worship in which the Israelites were brought up, consisted in sacrificing animals in those temples which contained certain images, to bow down to those images, and to burn incense before them; religious and ascetic persons were in those days the persons that were devoted to the service in the temples erected to the stars, as has been explained by us.

It was in accordance with the wisdom and plan of God, as displayed in the whole Creation, that He did not command us to give up and to discontinue all these manners of service; for to obey such a commandment it would have been contrary to the nature of man, who generally cleaves to that to which he is used; it would in those days have made the same impression as a prophet would make at present if he called us to the service of God and told us in His name, that we should not pray to Him, not fast, not seek His help in time of trouble; that we should serve Him in thought, and not by any action.

For this reason God allowed these kinds of service to continue; He transferred to His service that which had formerly served as a worship of created beings, and of things imaginary and unreal, and commanded us to serve Him in the same manner; namely, to build unto Him a temple; “And they shall make unto me a sanctuary” (Exodus 25:8); to have the altar erected to His name; “An altar of earth thou shalt make unto me” (ibid. 20:21); to offer the sacrifices to Him; “If any man of you bring an offering unto the Lord” (Leviticus 1:2), to bow down to Him and to burn incense before Him.

He has forbidden to do any of these things to any other being; “He who sacrifices unto any God, save the Lord only, he shall be utterly destroyed” (Exodus 22:19); “For thou shalt bow down to no other God” (ibid. 34:14). He selected priests for the service in the Temple; “And they shall minister unto me in the priest’s office” (ibid. 28:41). He made it obligatory that certain gifts, called the “gifts of the Levites and the priests”, should be assigned to them for their maintenance while they are engaged in the service of the Temple and its sacrifices. By this Divine plan, it was effected that the traces of idolatry were blotted out, and the truly great principle of our faith, the Existence and Unity of God, was firmly established; this result was thus obtained without deterring or confusing the minds of the people by the abolition of the service to which they were accustomed and which alone was familiar to them.

Incredibly, the Rambam believed that the sacrificial offerings were temporary, meant only to wean the people off of these pagan practices that they were familiar with. (For more on this, see the recent class on ‘Sacrifices & Veganism’.) God never intended for Jews to offer sacrifices, as we see in countless statements later in Tanakh that quote Hashem saying so, for example, I Samuel 15:22, “Does God delight in burnt offerings and sacrifices as much as in obedience to God’s command? Surely, obedience is better than sacrifice, to listen is better than the fat of rams!” Or Hosea 6:6, “For I desire goodness, not sacrifice; devotion to God, rather than burnt offerings.” Or Psalms 51:17-19, “My Lord, open my lips, and let my mouth declare Your praise. You do not want me to bring sacrifices; You do not desire burnt offerings; True sacrifice to God is a contrite spirit…” And perhaps most surprisingly, Jeremiah 7:21-23:

Thus said YHWH of Hosts, the God of Israel: Add your burnt offerings to your other sacrifices and eat the meat! For when I freed your ancestors from the land of Egypt, I did not speak with them or command them concerning burnt offerings or sacrifices. But this is what I commanded them: Do My bidding, that I may be your God and you may be My people; walk only in the way that I enjoin upon you, that it may go well with you.

So, how is it that in the Mishneh Torah the Rambam writes about the restoration of the sacrifices, but in the Guide he writes that sacrifices are no longer necessary and were never God’s intention to begin with? To properly understand the Rambam, we have to know that he held that there are “true beliefs”, and then there are “necessary beliefs”. Some things might be necessary to believe even if they are factually not quite true. The vast majority of the population can’t handle the ultimate truth, and must be taught the “necessary beliefs” (at least at the beginning). Only the educated and initiated can grasp the truth. And so, in his private letters, we see a lot more clearly who the real Rambam was, and what he truly believed. For instance, in his letter to Yosef ibn Aknin, he wrote:

Should you find any disagreements between the texts, it behooves you to go directly to the Talmud for relevant passages and you will discover the truth. Do not waste your time with the commentaries and casuistical explanations of obscure passages of the Gemara. I have abandoned those practices long ago as a waste of time and of little profit. May the Lord lead you in the right path.

The Rambam saw the Talmud as essentially a reference manual. He did not wish to spend his precious time on Talmudic dialectics and debates that have become so primary in yeshivas today. He saw all of those discussions, commentaries, arguments, the shakla v’tarya and the hair-splitting, as ultimately a “waste of time”. He wanted to get to the practical conclusions, and then spend his time learning the practical stuff: the maths and sciences, philosophy and metaphysics, medicine and the like. In his letter to the Jews of Marseilles, he further elaborated on this, and described his own scientific and rational worldview, writing:

Know, my masters, that no man should believe anything unless attested by one of three principles. First, rational proof as in mathematical sciences; secondly, the perception by one of the five senses… and thirdly, tradition derived from the prophets and the righteous… you should know that some misguided people wrote thousands of books on the subject and many ignorant people wasted their precious years pouring over them, mistaking vanity for knowledge and ascribing consummate wisdom to their authors. There seems to be a chronic disease which has become abysmally obsessive among most people, with the exception of a select divinely inspired remnant, to the effect that whatever is found in books is instantly acceptable as truth, especially if the books are ancient…

Again, the Rambam saw pouring over countless commentaries as a waste of time, and called people who do this ignorant of true wisdom. He recognized the “disease” of foolishly taking anything written in a sefer at face value, or believing that anything in a sefer must be automatically true or authentic. He even noted that the Talmud itself should not be assumed to be scientifically correct on every detail, writing in his Moreh Nevukhim (III, 14):

You must, however, not expect that everything our Sages say respecting astronomical matters should agree with observation, for mathematics were not fully developed in those days: and their statements were not based on the authority of the Prophets, but on the knowledge which they either themselves possessed or derived from contemporary men of science. But I will not on that account denounce what they say correctly in accordance with real fact, as untrue or accidentally true. On the contrary, whenever the words of a person can be interpreted in such a manner that they agree with fully established facts, it is the duty of every educated and honest man to do so.

Laying Down the Law

A bas relief of the Rambam in the US House of Representatives

The Rambam lived at a time when halakhah started to become very unclear. Rabbis in different regions ruled based on their own reasoning and understanding of the Talmud and the Geonic sources, meaning there was no universal standard. Meanwhile, every community was taking on their own local customs, or adopting practices from their neighbours. The result was total confusion as to the correct Jewish practice. This is what motivated the Rambam to write his code of law, the Mishneh Torah. The Mishneh Torah remains the only complete and comprehensive code of Jewish law, alone covering all aspects of Jewish law, even those that do not apply in a state of exile and without a Temple. In the Introduction, he explains:

וּמִפְּנֵי זֶה נִעַרְתִּי חָצְנִי אֲנִי משֶׁה בֶּן מַיְּמוֹן הַסְּפָרַדִּי וְנִשְׁעַנְתִּי עַל הַצּוּר בָּרוּךְ הוּא, וּבִינוֹתִי בְּכָל אֵלּוּ הַסְּפָרִים, וְרָאִיתִי לְחַבֵּר דְּבָרִים הַמִּתְבָּרְרִים מִכָּל אֵלּוּ הַחִבּוּרִים בְּעִנְיַן הָאָסוּר וְהַמֻּתָּר, הַטָּמֵא וְהַטָּהוֹר, עִם שְׁאָר דִּינֵי הַתּוֹרָה, כֻּלָּם בְּלָשׁוֹן בְּרוּרָה וְדֶרֶךְ קְצָרָה, עַד שֶׁתְּהֵא תּוֹרָה שֶׁבְּעַל פֶּה כֻּלָּהּ סְדוּרָה בְּפִי הַכֹּל בְּלֹא קֻשְׁיָא וְלֹא פֵּרוּק. לֹא זֶה אוֹמֵר בְּכֹה וְזֶה בְּכֹה – אֶלָּא דְּבָרִים בְּרוּרִים קְרוֹבִים נְכוֹנִים עַל פִי הַמִּשְׁפָּט אֲשֶׁר יִתְבָּאֵר מִכָּל אֵלּוּ הַחִבּוּרִים וְהַפֵּרוּשִׁים הַנִּמְצָאִים מִיְּמוֹת רַבֵּנוּ הַקָּדוֹשׁ וְעַד עַכְשָׁו…

Therefore, I girded my loins—I, Moses, the son of Maimon, the Sephardi. I relied upon the Rock, blessed be He. I contemplated all these texts and sought to compose a work which would include the conclusions derived from all these texts regarding the forbidden and the permitted, the impure and the pure, and the remainder of the Torah’s laws, all in clear and concise terms, so that the entire Oral Law could be organized in each person’s mouth without questions or objections. Instead of arguments, this one claiming such and another such, this text will allow for clear and correct statements based on the judgments that result from all the texts and explanations mentioned above, from the days of Rabbenu HaKadosh [Rabbi Yehuda haNasi, compiler of the Mishnah in the 2nd Century CE] until the present…

כְּלָלוֹ שֶׁל דָּבָר: כְּדֵי שֶׁלֹּא יְהֵא אָדָם צָרִיךְ לְחִבּוּר אַחֵר בָּעוֹלָם בְּדִין מִדִּינֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל, אֶלָּא יְהֵא חִבּוּר זֶה מִקְבָּץ לַתּוֹרָה שֶׁבְּעַל פֶּה כֻלָּהּ עִם הַתַּקָּנוֹת וְהַמִּנְהָגוֹת וְהַגְּזֵרוֹת שֶׁנַּעֲשׂוּ מִיְּמוֹת משֶׁה רַבֵּנוּ וְעַד חִבּוּר הַגְּמָרָא, וּכְמוֹ שֶׁפֵּרְשׁוּ לָנוּ הַגְּאוֹנִים בְּכָל חִבּוּרֵיהֶם שֶׁחִבְּרוּ אַחַר הַגְּמָרָא. לְפִיכָךְ קָרָאתִי שֵׁם חִבּוּר זֶה: מִשְׁנֵה תוֹרָה – לְפִי שֶׁאָדָם קוֹרֵא בַּתּוֹרָה שֶׁבִּכְתַב תְּחִלָּה וְאַחַר כָּךְ קוֹרֵא בָזֶה וְיוֹדֵעַ מִמֶּנּוּ תּוֹרָה שֶׁבְּעַל פֶּה כֻלָּהּ, וְאֵינוֹ צָרִיךְ לִקְרוֹת סֵפֶר אַחֵר בֵּינֵיהֶם.

The sum of the matter: a person will not need another text at all with regard to any Jewish law. Rather, this text will be a compilation of the entire Oral Law, including also the ordinances, customs, and decrees that were enacted from the time of Moses, our teacher, until the completion of the Talmud, as were explained by the Geonim in the texts they composed after the Talmud. Therefore, I have called this text Mishneh Torah with the intent that a person should first study the Written Law, and then study this text and comprehend the entire Oral Law from it, without having to study any other text between the two.

Incredibly, the Rambam states that all that a person really needs to learn to understand the entirety of Judaism and Jewish practice is the Torah of Moses, and his own Mishneh Torah! The Rambam knew he would be criticized for this, and even branded a “heretic”. In his letter to Yosef ibn Aknin, he wrote:

I was aware when I wrote the book that it would undoubtedly fall into the hands of evil obscurantists who would deliberately vilify its beauty and deprecate its value, thus reflecting their own shortcomings and ignorance. I likewise knew that the book would serve no purpose in the hands of the ignorant, incapable of evaluating its merit; or the confused upstart, unable to comprehend many passages because of a lack of fundamental assumptions, preventing him from grasping basic insights; or the self-styled intellectual—these groups will probably constitute the majority—accusing me of heretical tendencies in my basic beliefs.

Indeed, a few decades after his passing, his books were banned by the rabbis of France, who also went to the Christian authorities to stem the “heresy”, and the result was the public burning of Rambam’s books in Paris in 1233. This totally backfired on the rabbinic authorities, led by Rabbeinu Yonah (d. 1264), for it only opened the door for the Christians to start evaluating and censoring other Jewish texts. This climaxed in 1242 when the Christian authorities rounded up all copies of the Talmud and publicly burned them. Rabbeinu Yonah felt that this was a punishment for his campaign against the Rambam. To atone, he wrote Sha’arei Teshuva, “Gates of Repentance”, and vowed to journey to Israel and prostrate himself on the grave of the Rambam. Although he was unable to complete the journey, he did henceforth revere the Rambam and quote his works regularly.

The Rambam was also fiercely opposed by the chief rabbis of Iraq (Babylon). He described them as ignorant Talmudists who only profit from the donations of the masses, and who slander him without bothering to properly understanding his work. In his letter to Yosef ben Yehudah, he wrote about the attacks he was receiving from one of the Iraqi chief rabbis, responding: “He is a very foolish man. He works hard at his Talmudic discussion and its commentaries and thinks he is the greatest of his generation… why should I pay attention to an old man who is really miserable and an ignoramus in every respect?” (For more on this controversy, see here.)

Reincarnation & Afterlife

The Rambam described five different beliefs among Jews regarding the nature of the afterlife (see his commentary on the tenth chapter of Sanhedrin). After all, the Torah itself never explicitly speaks of any afterlife, and provides no description of a Heaven or Hell, leaving plenty of room for speculation. One of the fundamental beliefs of Judaism is that there certainly is an afterlife, and one earns their reward or punishment for their deeds in this world, but exactly what that afterlife looks like is open to a great deal of debate and interpretation. What did the Rambam himself believe?

In his Commentary on the Mishnah, he lists the belief in a physical Resurrection of the Dead as one of the fundamentals of Jewish faith. Yet, he never seems to mention this again in his later works! No such belief is discussed in either the Mishneh Torah or Moreh Nevukhim. Instead, the Rambam speaks only of an entirely spiritual afterlife, with no corporeality or return to bodily form at all. In his letter to Yosef ibn Gabir, the Rambam explains:

Accordingly, you should not attempt to apprehend anything other than what your mind can grasp. It will not harm you religiously to think that there are corporeal beings in the World to Come until you can establish rationally the authentic nature of their existence. Even if you think that they eat, drink, propagate in the upper sphere or in Gan Eden, it will not hurt your faith. There are other more widespread doctrinal follies to which some cling and yet their basic religious beliefs were not damaged. But in refutation of this notion, it is important to project the authentic interpretation of the rabbinic statement “there is no eating or drinking in the World to Come” from which we may deduce that there are no corporeal beings…

Again, we see here a discrepancy between a “true belief” and a “necessary belief”. According to the Rambam, a simple-minded person might believe in a physical resurrection into bodily form—and this is okay to believe religiously and will not “hurt one’s faith”—but the true initiate understands that the afterlife is entirely spiritual, with no corporeality at all.

So what about reincarnation? The above statement might suggest that the Rambam would reject reincarnation. But we’re not quite sure, because he never spoke about it at all. The Rambam was surely aware of the concept, yet never seems to mention it or speak of it. This is in stark contrast to his predecessor, Rav Saadia Gaon (c. 882-942), who famously rejected reincarnation and believed it to be a foolish idea adopted from the Gentiles. The Rambam was a big admirer of Saadia Gaon, who had actually laid the groundwork for the Rambam. Saadia Gaon wrote the first texts synthesizing Torah and philosophy (most notably his Emunot v’De’ot), and some of the first works in Judeo-Arabic, as the Rambam would later do. In his Letter to Yemen, the Rambam wrote that “Were it not for Rav Saadia Gaon, the Torah would have all but disappeared from the Jewish people. For it was he who shed light on that which was obscure, strengthened that which had been weakened, and spread the Torah far and wide, by word of mouth and in writing.”

Surely, the Rambam knew Rav Saadia Gaon’s position on reincarnation, but was silent about it himself. Reincarnation was also discussed by the Greek philosophers, especially Pythagoras, who was a big champion of reincarnation. The Rambam was an expert in Greek philosophy, so there is no doubt he knew about reincarnation. Thus, the Rambam’s conspicuous silence on reincarnation might suggest that he actually accepted it, or at the very least, accepted it as a legitimate possibility. Otherwise, he would have surely said something about it (as Saadia Gaon did), since he was not one to shy away from criticizing beliefs he deemed foolish or false.

Intriguingly, one might go so far as to suggest that the Rambam was a reincarnation of Moshe Rabbeinu! Think about it: both were named Moshe, both were great leaders of the Jewish people with numerous critics, both lived in Egypt, both interacted with Egyptian royalty, both described their difficult burden leading the people, and both wished to live in Israel but couldn’t. In the case of the Rambam, he did merit to visit Israel and ascend the Temple Mount, and it was such a great highlight of his life that he established it as a holiday for his family. One might see this as a sort of tikkun for Moshe Rabbeinu, who deeply wished to visit Israel but was forbidden from doing so (although Hashem did give him an aerial overview).

Moshe ben Amram gave us the Written Law, Moshe ben Maimon codified the Oral Law. Moshe ben Amram gave us the Torah, Moshe ben Maimon gave us the Mishneh Torah. And he had the audacity to say in his Introduction that one need only read the Torah of Moses and his Mishneh Torah to know everything there is to know about Judaism! It might even explain why we always read Parashat Shemot, recounting the birth and rise of Moses, right around the Rambam’s yahrzeit, as we do this week. And it would certainly explain the famous adage that miMoshe ad Moshe lo kam od k’Moshe:

“From Moshe [Rabbeinu] to Moshe [Rambam] there arose no other like Moshe!”