770 Eastern Parkway, global headquarters of Chabad

At the start of this week’s parasha, Vayetze, Jacob sees a vision of a Heavenly Ladder and receives a blessing from God. He is told: “you shall break out [u’faratzta] westward and eastward and northward and southward; and through you shall be blessed all the families of the Earth and through your seed.” (Genesis 28:14) The term u’faratzta, translated as “break out” or “gain strength” or “spread out”, is something of a slogan and rallying cry among Chabad Hasidim, who’ve made it their mission to bring Judaism to every corner of the globe, “westward, eastward, northward, southward”. It has further significance for Chabad because the verb faratzta (פרצת) has a numerical value of 770, as if alluding to Chabad headquarters at 770 Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn. It was the seventh and last Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902-1994), who transformed Chabad from a small Hasidic group into an international phenomenon. What was his vision? Why did he want to put a “Chabad House” within reach of every Jew around the globe? And what does it really have to do with bringing Mashiach and the Final Redemption?

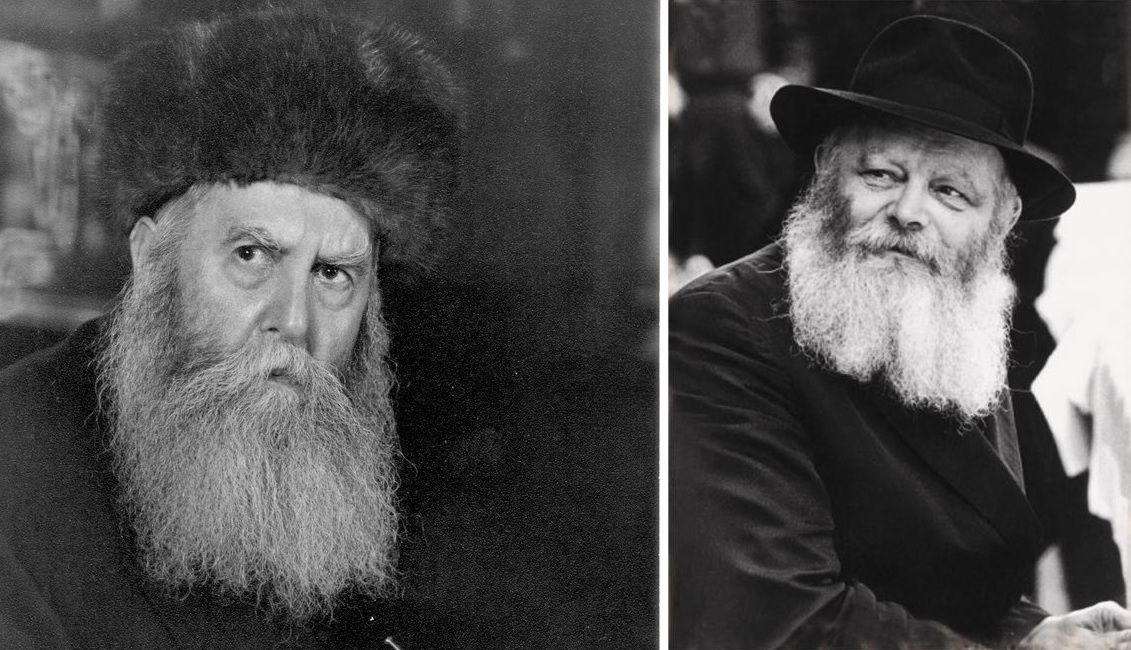

The sixth and seventh Lubavitcher Rebbes.

In 1940, the previous Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn (1880-1950) arrived in New York City, having fled Warsaw following the Nazi invasion. As the Rebbe was in a wheelchair, he needed an accessible home. A former medical office at 770 Eastern Parkway was the perfect choice, and was purchased for him to live in and to serve as the Chabad main office. His son-in-law (who would become the next Rebbe in 1951) arrived the following year, was put in charge of Chabad’s educational arm, Merkos L’Inyonei Chinuch, and got some office space on the first floor, too. He would take over the movement in those critical years following the Holocaust and the founding of the State of Israel. While his predecessors were officially “anti-Zionist”, the new Lubavitcher Rebbe took a different approach, engaging closely with the State and advising its leaders regularly. While he never visited Israel, he actually never left New York at all from the time he became Rebbe. The groundbreaking events that took place in the years before he took on Chabad leadership had an indelible impact on his vision and philosophy. He was convinced that the time for Redemption had arrived, and he made it clear in his very first discourse, Basi l’Gani.

The Rebbe explained that the seventh generation of Chabad had begun, as he was the seventh rebbe since the Alter Rebbe, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi (1745-1812), the founder of Chabad. This was comparable to Moses, the seventh generation from Abraham. It was that seventh generation of Moses, the “First Redeemer”, that merited the divine revelation at Mount Sinai. So, too, the Rebbe said, this seventh generation of Chabad would live to see the final divine revelation with Mashiach, the “Final Redeemer”. In his first discourse, the Rebbe made clear that “The spiritual task of the seventh generation is to draw down the Shekhinah truly below…” The Divine Presence must be made manifest in this material world. How is this to be done? The Rebbe said we must remember that “the quality of the seventh of a series is merely that he is seventh to the first” so we must look to the initial mission of the first generation, and finish the job now in the seventh. We must be like the first generation, “like Abraham: arriving in places where nothing was known of Godliness, nothing was known of Judaism, nothing was even known of the alef beit, and while there setting oneself completely aside [to call in God’s Name, as Abraham did].” Torah, mitzvot, and knowledge of God has to be spread as far and wide as possible, u’faratzta!

The Rebbe saw the events of the previous years as being a fulfilment of ancient prophecies about the End of Days, and thus the time was ripe for Redemption. He concluded his discourse like this: “Since we have already experienced all these things, everything now depends only on us—the seventh generation.” Henceforth, his entire mission was centered around bringing that Redemption. A decade later, however, no Redemption had arrived. The Rebbe understood that we must not be doing enough, and need to double down our efforts. In a discourse on Lag b’Omer 1962, the Rebbe explained that we all must be like Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai (“Rashbi”, whose mystical teachings we celebrate on Lag b’Omer):

[Rabbi Shimon] did not wait until he saw a problem, and then set out to correct it. Instead, he sought out problems to correct, asking others: “Is there anything that I could rectify?” And when he was told that there was a place which priests avoided because of a question of ritual impurity, he set out to correct the difficulty. Although the question involved impurity contracted from a human corpse—the most serious form of ritual impurity—Rabbi Shimon was able to make the place suitable even for priests. (Likkutei Sichos, Vol. VIII, pg. 131)

The Rebbe explained that Rashbi was not afraid to go to places of great impurity in order to affect spiritual rectifications. Moreover, the Rebbe continued:

Our Sages also quote Rabbi Shimon as saying: “I can acquit every Jew from the attribute of judgement.” Although there are people who have committed undesirable acts, Rabbi Shimon was able to find grounds for their defense… Rabbi Shimon was willing and able to descend to such a low level because he was among “the superior men who are few in number.”

In other words, Rashbi was one of the first “kiruv rabbis” who went out of his way to reach out to wayward and unobservant Jews. He would see every Jew in a positive light, and find a redeeming quality within them. He would find sinners and help them get back on the right path. He could descend even to the lowest places on Earth without fear of being sullied by the impure surroundings. This has become a fundamental of Chabad philosophy, with Chabad emissaries showing unparalleled ahavat Israel and being widely beloved for their non-judgemental attitude and open arms, along with a willingness to connect with all kinds of Jews on every street corner. Finally, the Rebbe concluded:

… the stories about Rabbi Shimon’s conduct serve as a directive for every Jew in later generations. This has been particularly true ever since the teachings of Pnimiyus haTorah [inner mystical dimensions of Torah], the wisdom of Rabbi Shimon, were revealed. Following Rabbi Shimon’s example, it is necessary for us to “spread the wellsprings outward” to join the two ends of the spiritual spectrum… and spread the “water” to the most extreme peripheries. This will prepare the world for the coming of Mashiach, who will likewise join two extremes… the Redemption will come when the outlook of Rabbi Shimon—who stood above the destruction of the Beit HaMikdash—is spread throughout the world. Rabbi Shimon’s teachings must be spread everywhere, even in places which need correction, even in places which are ritually impure…

The Rebbe here was alluding to a well-known story about the Baal Shem Tov, Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer (1698-1760, founder of Hasidism), who described in a letter how he ascended to Heaven and met Mashiach. When the Baal Shem Tov asked Mashiach when he would come, Mashiach replied that he would come when the Baal Shem Tov’s “wellsprings”, his mystical teachings, would spread worldwide. In this discourse, the Rebbe took things a step further in saying that the wellsprings must spread not only to established Jewish communities around the world or to other receptive audiences, but everywhere, “to the most extreme peripheries”, to the most impure of places.

While the Rebbe had sent emissaries (“shluchim”) to various communities from the very start of his tenure, now he was going to send them even to places of impurity, immorality, and secularism. In 1965, he sent Rabbi Shlomo Cunin to Los Angeles to work specifically with university students, plunging him into the heart of the liberal world at the height of the hippie movement. Four years later, Rabbi Cunin established the first official “Chabad House” at UCLA. In 1972, on his 70th birthday, the Rebbe famously requested a gift from his Hasidim: to open up another 71 Chabad Houses before his 71st birthday! That same year, Rabbi Cunin expanded to UC Berkeley and UC San Diego. The model was quickly replicated around the world, and the rest is history. Today, there are over 5000 Chabad Houses and Chabad institutions in over 100 countries.

While each Chabad institution is really stand-alone and is expected to raise its own funds and manage its own activities, the overall movement is still centrally-run and guided from 770 Eastern Parkway. The headquarters has become something of a shrine and temple of its own. Replicas of the building have been built in other parts of the world, including Jerusalem and Australia. Of course, many within Chabad believe the Rebbe to have been Mashiach (a question we addressed before here), and find proof within the fact that 770 is the value of “Mashiach’s House” (בית משיח), and more support in that the house is in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighbourhood. Some within Chabad believe that when Mashiach comes, 770 will be miraculously transported to Jerusalem. A minority fringe has even associated it with the Third Temple itself!

Replicas of 770 in Melbourne, Australia; and in Kfar Chabad and Jerusalem, Israel

Now, there is no doubt that the Lubavitcher Rebbe was a complete tzadik and did more for kiruv in absolute terms than anyone else in history. Nor is there any doubt that no one has done more to bring the Redemption than he did. It is pretty safe to say that while he was alive, he was probably the “presumptive messiah” of the generation, and it is clear from his own teachings that he hoped himself to be as well. Alas, it wasn’t meant to be. The Rebbe delivered a difficult speech in April 1991 where he seemingly “gave up”, and left his Hasidim totally confounded. Elderly and frail, just months before suffering a debilitating stroke that left him unable to speak and partially paralyzed, the tearful Rebbe said:

How is it that the Redemption has not yet been attained? That despite all that has transpired and all that has been done, Mashiach has still not come? What more can I do? I have done all I can to bring the world to truly demand and clamour for the Redemption…The only thing that remains for me to do is to give over the matter to you. Do all that is in your power to achieve this thing—a most sublime and transcendent light that needs to be brought down into our world… I have done all I can. I give it over to you. Do all that you can to bring the righteous redeemer, immediately! I have done my part. From this point on, all is in your hands…

Sadly, the Rebbe passed away three years later. Nonetheless, within Chabad there are still those who believe the Rebbe is somehow Mashiach, despite the fact that he has been gone for nearly three decades. Some go even further and hold him to have some kind of divine status. No one is quite sure how prevalent these beliefs are within Chabad, and whether they are subsiding or actually growing stronger. Some say it is only a vocal tiny minority that continues to believe, while others argue there is definitely a silent majority. This puts Chabad in a precarious position:

On the one hand, Chabad is the most successful Jewish organization of all time, with massive resources and many adherents, with branches all over the world touching just about every Jewish community. (A 2005 survey found that over a million Jews attend a Chabad service at least once a year.) Chabad is an absolute success, and has the potential to become the dominant form of Judaism worldwide.

On the other hand, if the messianic fervour does not dissipate, or if it gets stronger, Chabad risks following in the footsteps of other Jewish messianic sects that ended up splitting into their own religions over time, forever waiting for the “second coming” of their messiah. Much depends on Chabad leadership, and what will happen as the older generation passes on and is replaced by younger idealists. It remains to be seen which of the two possibilities materialize in the coming decades: will Chabad save Judaism, or will it fracture it? As someone who had his bar mitzvah at a Chabad synagogue, was married by a Chabad rabbi (alongside a Bukharian one), prayed with a Chabad minyan for many years, and still occasionally participates in Chabad services, I very much hope that it will be the former.

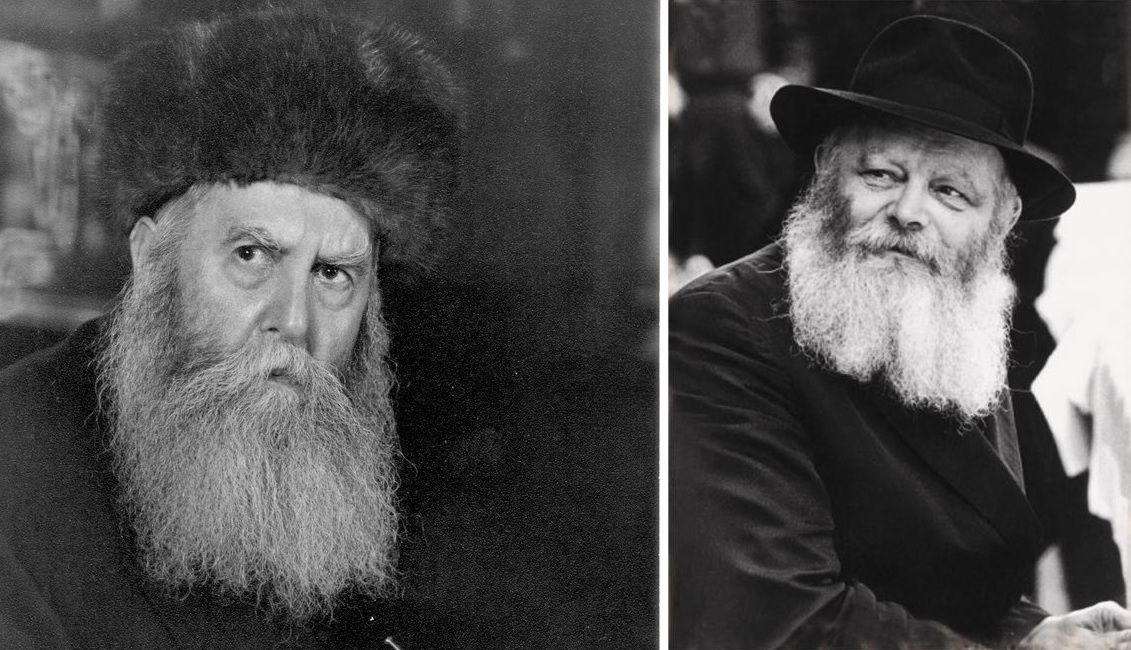

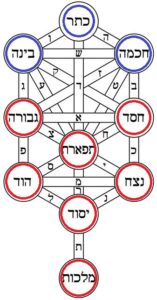

Putting it all together, we can propose that the flowing liquid log measurement is to teach us to measure and refine ourselves spiritually during this period of time. The value of log (לג) is 33 to remind us of the 33 vertebrae that line the spinal cord at birth—representing our ascent from the animalistic base where waste is excreted, to the lofty brain capable of divine intellect. These 33 bones fuse into 26 vertebrae by adulthood, 26 being the numerical value of God’s Ineffable Name, reminding us of our goal in striving ever-higher towards Hashem. And 33 reminds us of King David’s words: gal einai (גל עיני), “Open my eyes so that I can see the wonders of your Torah!” (Psalms 119:18) Now is a time to be particularly focused on Torah and mitzvot, prayer and meditation, mystical pursuits and spiritual growth.

Putting it all together, we can propose that the flowing liquid log measurement is to teach us to measure and refine ourselves spiritually during this period of time. The value of log (לג) is 33 to remind us of the 33 vertebrae that line the spinal cord at birth—representing our ascent from the animalistic base where waste is excreted, to the lofty brain capable of divine intellect. These 33 bones fuse into 26 vertebrae by adulthood, 26 being the numerical value of God’s Ineffable Name, reminding us of our goal in striving ever-higher towards Hashem. And 33 reminds us of King David’s words: gal einai (גל עיני), “Open my eyes so that I can see the wonders of your Torah!” (Psalms 119:18) Now is a time to be particularly focused on Torah and mitzvot, prayer and meditation, mystical pursuits and spiritual growth.