This Saturday night marks Lag b’Omer, the 33rd day of the Sefirat haOmer counting period and a day to celebrate the mystical side of Judaism. The term omer is a Biblical unit of measure, a dry weight for sheaves of grain (equal to about one and a half kilograms). Recall that in Temple times, the kohanim would wave a sheaf of barley as an offering, and to signify the start of the new barley harvest. From that day forward, they would count each day. Then, on the fiftieth day—Shavuot—they would present a wheat offering of two omers.

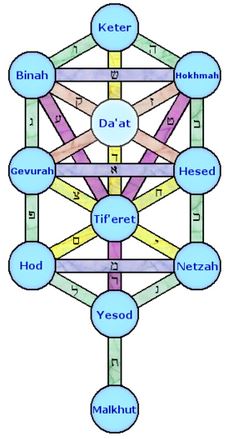

The Sefirot of Mochin above (in blue) and the Sefirot of the Middot below (in red) on the mystical “Tree of Life”.

We find that all of these procedures seem to involve counting, numbering, and measuring. The deeper significance here is to teach us that each person needs to do a detailed “accounting” of their soul, of their deeds, and of their life—measure by measure, down to the last unit. Indeed, the Sefirat haOmer period has long been one of introspection and personal development. From a mystical perspective, we are meant to focus on each of the seven main qualities of a human, the middot, literally “measures”. In Biblical times, they would measure sheaves of grain and elevate them before God; today, we “measure” our own inner qualities and elevate ourselves.

While Shavuot is the conclusion of the counting period, the middle apex is Lag b’Omer. Interestingly, the term lag (ל״ג) is not just a number, but actually a word found in the Torah. In Leviticus 14, we find it mentioned five times as log (לֹג), another Biblical unit of measure! Unlike the dry omer, the log is a liquid measure (about half a litre). Thus, one could read the name of the holiday Lag b’Omer as “a liquid measure in a dry measure”. What might this signify? What is the symbolic difference between the two measures, and what exactly are we supposed to be “measuring” within us?

We find that the log was used in measuring oil volume during the spiritual purification of the metzora “leper”. In fact, the word log is used five times in the purification procedure of Leviticus 14, perhaps alluding to the five aspects of the soul (nefesh, ruach, neshamah, chaya, yechidah). The omer, meanwhile, was for measuring produce and sustenance. In addition to the omer sheaf in the Temple, the Israelites in the Wilderness received an omer of manna each day (Exodus 16:16). Plus, God commanded that one omer of manna be placed in a special jar to be put on display in the Mishkan as a souvenir for the future (16:33).

The Torah tells us that the manna began to fall about a month after the Exodus, when the Israelites ran out of provisions that they took with them out of Egypt. Thus, according to Rashi, the Israelites began receiving the manna on the 16th of Iyar (see his comments on Kiddushin 38a). Yet, there is another tradition (as cited by the Chatam Sofer in his responsa on Yoreh De’ah 233) that the Israelites actually went three days without food, before God produced a miracle for the starving nation on the 18th of Iyar. In other words, Lag b’Omer also commemorates the miraculous day when omers of manna first began to fall for Israel!

Spiritual and Physical Measures

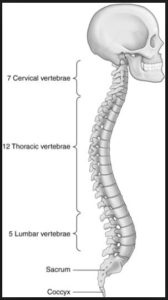

Putting it all together, we can propose that the flowing liquid log measurement is to teach us to measure and refine ourselves spiritually during this period of time. The value of log (לג) is 33 to remind us of the 33 vertebrae that line the spinal cord at birth—representing our ascent from the animalistic base where waste is excreted, to the lofty brain capable of divine intellect. These 33 bones fuse into 26 vertebrae by adulthood, 26 being the numerical value of God’s Ineffable Name, reminding us of our goal in striving ever-higher towards Hashem. And 33 reminds us of King David’s words: gal einai (גל עיני), “Open my eyes so that I can see the wonders of your Torah!” (Psalms 119:18) Now is a time to be particularly focused on Torah and mitzvot, prayer and meditation, mystical pursuits and spiritual growth.

Putting it all together, we can propose that the flowing liquid log measurement is to teach us to measure and refine ourselves spiritually during this period of time. The value of log (לג) is 33 to remind us of the 33 vertebrae that line the spinal cord at birth—representing our ascent from the animalistic base where waste is excreted, to the lofty brain capable of divine intellect. These 33 bones fuse into 26 vertebrae by adulthood, 26 being the numerical value of God’s Ineffable Name, reminding us of our goal in striving ever-higher towards Hashem. And 33 reminds us of King David’s words: gal einai (גל עיני), “Open my eyes so that I can see the wonders of your Torah!” (Psalms 119:18) Now is a time to be particularly focused on Torah and mitzvot, prayer and meditation, mystical pursuits and spiritual growth.

That said, as much as we are focusing on our spiritual side, we should not lose sight of the body, symbolized by the dry omer measure used for those sheaves of grain and the healthy omers of manna consumed by the Israelites. The omer reminds us that we must also refine ourselves physically, maintain good health and balanced diets; work productively, exercise, and strengthen our bodies. As explored in the past, it is unlikely that a weak body could contain a great soul. The state of the vessel is tremendously important, too.

Thus, hidden within the very name “Lag b’Omer” is a reminder of the two sides of personal development: spiritual and physical. We must never give so much attention to one that we neglect the other; both are needed in balance. This is the way to becoming a complete and wholesome human, as God intended. Such a person becomes like Moses, described as a “Godly man” and the greatest prophet (Psalm 90:1), but also as physically domineering and able to defeat the giant Og, with his bodily strength and vigour undiminished to his last days (Deuteronomy 34:7). It isn’t surprising that the value of “Moshe” (משה) is 345, exactly equal to “Lag b’Omer” (לג בעמר)! And it is further fitting that omer (עמר) is spelled without a vav in the Torah, making its value 310, reminding us of the 310 worlds awarded to the righteous in the World to Come (Uktzin 3:12). It takes lag b’omer to get there: a balance of one’s “liquid” and “dry” measures, of the spiritual and the physical, of both Heavenly ascent and Earthly strength. May Hashem guide each of us to achieve that level.