This week we start a new book of the Torah, Shemot, known in English as ‘Exodus’. This volume is primarily concerned with the period of Israelite slavery in Egypt, and the subsequent salvation following the ten plagues and the Splitting of the Sea, climaxing with the revelation at Mt. Sinai, and the start of the transmission of the bulk of the Torah’s laws.

Coincidentally, not long ago was released Ridley Scott’s new film, Exodus: Gods and Kings, and I finally had a chance to see it this week. Though it appeared to show a little bit of promise at the start, the movie soon unravelled into a bizarre re-invention of the Biblical story. Of course, there is nothing wrong with some artistic liberties when adapting an ancient text for a modern film, nor is it too much of a problem to fill in some of the gaps in the Torah’s narrative. However, Exodus: Gods and Kings presented a completely twisted version that did not even slightly stick to the basic story of the Torah. It would take an entire tome to cover all the mistakes in the film, but perhaps we can offer just a few of the most blatant ones.

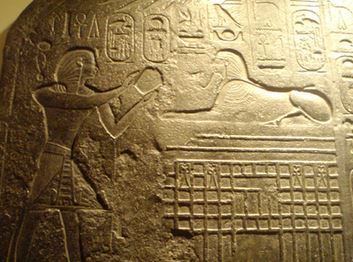

From the very beginning, we see that Moses seems to be completely unaware that he is not Egyptian. That’s quite odd: Semites and Egyptians had a totally different appearance. Take a look at this depiction of Semitic tribes, as discovered in the 12th dynasty tomb of Egyptian Khnumhotep II, official of the pharaoh Senusret II:

The Semites have a different skin tone, different hair styles, clothes, and so on. The filmmakers clearly knew this, as they show Moses bearded and sporting a nice hairdo, while all the other Egyptian royals are clean-shaven and bald. His eyes look different, and he wears clothes of a completely different style than all the others. How come? Didn’t he ever question why he doesn’t look anything like his “royal brethren”?

More importantly, the Torah clearly says that Moses was initially raised by his true birth mother, Yocheved (Exodus 2:7-9). Only after he was fully weaned did Yocheved present Moses to his new step-mother, the Pharaoh’s daughter (v. 10). It is totally inconceivable that Moses did not know he was a Hebrew! The Torah states that when Moses grew up, he “went out to his brothers and looked at their burdens” (2:11). He knew full-well that he was going out to his people.

At this point, when he saw an Egyptian taskmaster violently beating a Jew, he stepped in to save the victim, killing the Egyptian in the process. In the movie, this heroic act is replaced with an enraged Moses killing an Egyptian guard who was doing nothing terrible at all. The kind, compassionate Moses, described by the Torah as the humblest man that ever lived, is turned into a violent brute who kills indiscriminately. No wonder that Christian Bale, the actor who plays Moses, said of his character that he was “likely schizophrenic and was one of the most barbaric individuals that I ever read about in my life.” Makes sense if all he ever read about Moses was in the script for the film.

If Christian Bale did indeed read about Moses, perhaps he missed the whole part where Moses selflessly led his people for forty years in the wilderness. Where he literally sat from morning to evening to counsel the people and help them (Exodus 18:13). Or when he refused to abandon his people, even when God offered to make an entirely new nation out of Moses (Exodus 32:10). The many occasions where he convinced God to avert His just decrees and forgive the nation for their sins. The time where his sister Miriam transgressed severely against Moses, yet he did not hold even the tiniest of grudges or ill-will, and immediately prayed to God to heal Miriam and have mercy on her (Numbers 12:13). Or the simple fact that Moses led the revolution that brought monotheism (together with a higher sense of morality, starting with a set of Ten Commandments) to over two-thirds of the world’s population.

Worse than its depiction of Moses, though, was the film’s depiction of God: an irrational, pointlessly vengeful, literally childish figure. The film made it seem like the Ten Plagues were nothing more than God’s desire to kill as many people as possible. The reality, of course, was that the Ten Plagues were meant to be a measure-for-measure retribution for what the Egyptians had done; nothing more than cosmic karma. For example, just as the whole story begins with Pharaoh ordering the male-born to be drowned in the Nile, it ends with Pharaoh’s own male soldiers drowning in the Red Sea, measure for measure. Nor was God happy about any of this. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 39b) beautifully says that at the Splitting of the Sea, when the Egyptians drowned, the angels began to sing a joyous song, mimicking the Jews that were singing as well – but God immediately stopped them. He rebuked the angels, saying sadly: “My creations are drowning, and you are singing?”

When one studies the texts and commentaries, it becomes clear that each of the Plagues was specifically tailored towards the sins of the Egyptians, and was designed to bring the rightful justice that was due. Nowhere is this fact even hinted to in the movie. Most telling was after the plague of the firstborn, when Pharaoh confronts Moses demanding an answer as to why they suffered such a tragedy. The latter gives no logical reply, saying only that no Hebrews died. Perhaps the scriptwriter should have had something along the lines of: “Hey Pharaoh, did you forget all the countless babies that you slaughtered? Or the many warnings you were given that this was coming, and to stop your evil ways?” The scene almost makes Pharaoh seem like the victim, and Moses the villain. It appears that the main aim of the movie was to cast Moses (and God) in a bad light. It really seems like the filmmakers went out of their way to do this.

Moses is shown carelessly abandoning his family when he goes back to Egypt to save his people. His wife and son are angry, emotionally-scarred, losing their faith – and Moses does nothing about it. What was the point of making this shift from the Torah’s original version, which clearly states “Moses took his wife and sons, mounted them upon the donkey, and returned to the land of Egypt…” (Exodus 4:20)? He never abandoned his family, but took everyone with him!

It therefore appears quite evident that the purpose of Exodus: Gods and Kings was to turn one of the most beautiful and enduring stories into an ugly, twisted, and corrupt tale. The sheer number of mistakes is both inexcusable and inexplicable. One who wishes to experience a far truer (and more entertaining) version need only to open and read this week’s Torah portion.