‘Destruction of Leviathan’ by Gustav Doré

In this week’s parasha, Va’era, we read about Moses’ first confrontation with Pharaoh and the famous battle of their serpentine staffs. Interestingly, in last week’s parasha when Moses’ staff first turned into a serpent (Exodus 4:3), the word used was nachash, while this time it says tanin (7:9-10)! The former term certainly means a “snake”, but the latter is more general and can be any serpent, reptile, or even crocodile. Mystical texts see this as an allusion to the greatest of the taninim, created by God on the Fifth Day of Creation, the great sea dragon called Leviathan. The Zohar (II, 27b) comments here that the Leviathan was red like a rose, with iron-like scales, wing-like fins, a powerfully-thrashing tail, and fire coming out of its mouth. It has long migrations in the deep seas lasting seventy years.

Commenting on the words hataninim hagedolim, “the great sea monsters”, in Genesis 1:21, Rashi says that God originally created a pair of Leviathans, but they were so terrible that He slew the female so that the couple wouldn’t reproduce. God then “salted” its flesh and preserved it for the righteous in the World to Come, who are said to enjoy it at the “Feast of Leviathan” in the End of Days. Rashi is quoting the Talmud here (Bava Batra 74b-75a), which adds that God will make a sukkah for the tzadikim from the skin of the Leviathan. The leftover skin will be draped over “the walls of Jerusalem” and will shine and glow to wow the entire world. Perhaps that means the Kotel will have a miraculous new look in the near future, which is quite fitting since it will no longer be a “wailing” wall.

We read here in the Talmud that God castrated the male Leviathan, too, and provides a Scriptural source for it all in Isaiah 27:1, that “He will slay the Serpent that is in the sea…” The Sages ask: why did God slay the female and not the male? One answer is that the female could have still laid eggs without the male. Indeed, we know scientifically that there is a phenomenon called parthenogenesis where female fish are able to reproduce even without fertilization by a male. The Talmud then gives another answer based on Psalms 104:26, which says “There is Leviathan, whom You have formed to sport with.” God created the Leviathan just to “sport with”, and it wouldn’t be appropriate to sport with a female Leviathan, so he left the male only. (It seems gender segregation in sports is not a new issue!)

There is a way to interpret all of this metaphorically, too, and the Talmud goes on to say that the Jordan River flows into the “mouth of Leviathan”, while the ancient Seder Rabbah d’Beresheet says the entire planet “rests” on one of the fins of Leviathan. Even the Zohar has an interesting interpretation of the taninim gedolim of Creation, saying they are actually referring to the “Seventy Princes”, the Heavenly angels overseeing the seventy nations of the world. Leviathan is chief among them. From other sources, we learn that the chief of all the Seventy Princes is the angel Metatron (ie. Enoch), so we find here a link between the great Metatron and Leviathan. (This is further appropriate because the earliest known reference to a “Feast of Leviathan” is actually the apocryphal Book of Enoch!)

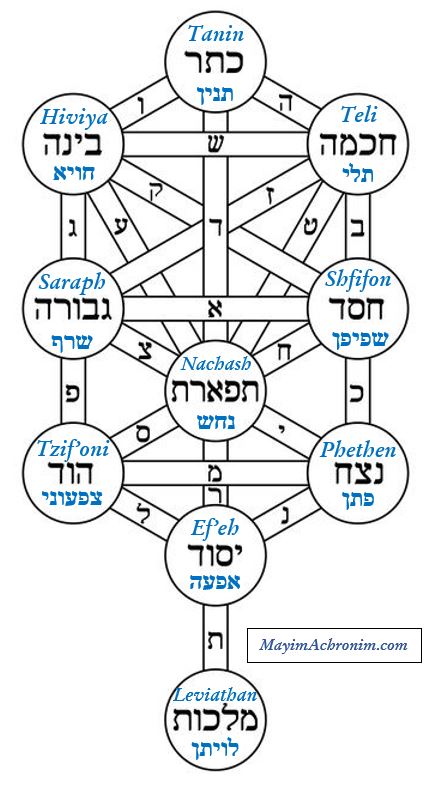

Mystical texts say the spirit of Metatron is found within Mashiach (see, for instance, Kol haTor), and Mashiach is destined to slay the remaining Leviathan at the End of Days, ushering in the final Kingdom of God on Earth. This, too, might be a metaphor for Mashiach subduing all seventy nations and unifying them under one God, as we read in Zechariah 14:9 that “Hashem shall be king over the entire Earth; on that day Hashem will be one and His name will be one.” In fact, the numerical value of “Leviathan” (לויתן) is 496, equal to Malkhut (מלכות), “Kingdom”. Leviathan thus corresponds to the last of the Sefirot. (We explored in the past how the changing astronomical constellations in the sky above us are shifting now to reveal this very process.) Intriguingly, we find six other terms for serpents throughout the Tanakh, and they neatly parallel the six other “lower” Sefirot from Chessed to Yesod.

The Seven (Eight?) Serpents

The most common term for a serpent is, of course, nachash. This snake corresponds to the central Sefirah of Tiferet. Tiferet is the spiritual root of all Israel, and of Mashiach in particular. This is another reason why the values of nachash (נחש) and “Mashiach” (משיח) are equal, both being 358. When Jacob blessed his son Dan, he saw a vision of Mashiach and said “I await Your salvation, Hashem!” (Genesis 49:18) Before that, Jacob fittingly described Mashiach (while seemingly speaking of Dan) as a nachash ‘alei derekh, a “snake upon the road”.

He then used another serpentine term, saying that Mashiach should also be a shfifon ‘alei orach, typically translated as a “viper upon the path”. The Maharal (Rabbi Yehuda Loew of Prague, c. 1512-1609) in Gur Aryeh connects this mysterious term with several roots, including the humbling shofef, as well as neshef, meaning an “exhale” or a “relaxation” or even a happy gathering of some sort. The shfifon (שפיפן) has positive energy, and corresponds to the loving Sefirah of Chessed. Jacob was possibly alluding to Mashiach’s role to bring all of Israel together and reconnect them spiritually through various “paths”.

On the opposite side of the Sefirotic tree we have the fiery and judging Gevurah. This corresponds to the Torah’s saraph (שרף), a “burning” venomous snake that God used to punish the people in the Wilderness for their rebelliousness (Numbers 21). To heal the people, Moses then made a nachash nechoshet, a copper serpentine rod. Now we can understand why it had to be specifically a nachash because, as we saw above, that one corresponds to Tiferet, which is said to be the source of healing and shares a root with refuah! Mashiach, too, is said to carry a serpentine staff. In fact, the Midrash and Zohar state that a woman called “Heftzibah” will bring it to him, finding it somewhere in Tiberias where Eliyahu hid it. She is also known as Mevaseret Tzion, the “Herald of Zion”, as per Isaiah 40:9 (see Sefer Zerubbabel and Zohar III, 173b).

Next, we have the “twin” Sefirot of Netzach and Hod, corresponding to the legs. They are always referred to as being the source of prophecy. In Psalm 91 we read “You will tread on lion cubs and phethen…” The phethen (פתן) is none other than the python. It is worth noting that in ancient Greece, the python was associated with prophecy, and their prophetic Oracle at Delphi was called Pythia. In the famous messianic prophecy of Isaiah, we read of another serpent paralleling the python: “A babe shall play over the hole of a phethen, and an infant pass its hand over the den of a tzif’oni.” (11:8) The word used for a “den” here is me’urat, which can be read as m’orat, ie. “from the light [or fire] of the tzif’oni”. The Malbim (Rabbi Meir Leibush Wisser, 1809-1879) reads it this way, saying the “fiery” poison of the tzif’oni (צפעוני) will no longer harm a child in the Messianic Age. This gives us a clue that the tzif’oni corresponds to Hod, lying beneath the fiery Sefirah of Gevurah, and tempering its judgement. More significantly, we can learn from this Isaiah verse that in the Messianic Age, even a child will be able to connect to Netzach and Hod and attain the light of prophecy.

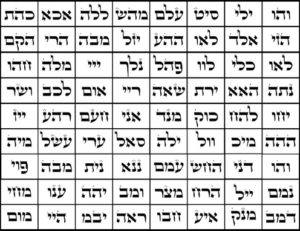

The 72 Names of God (For the origin of these Names, see here.)

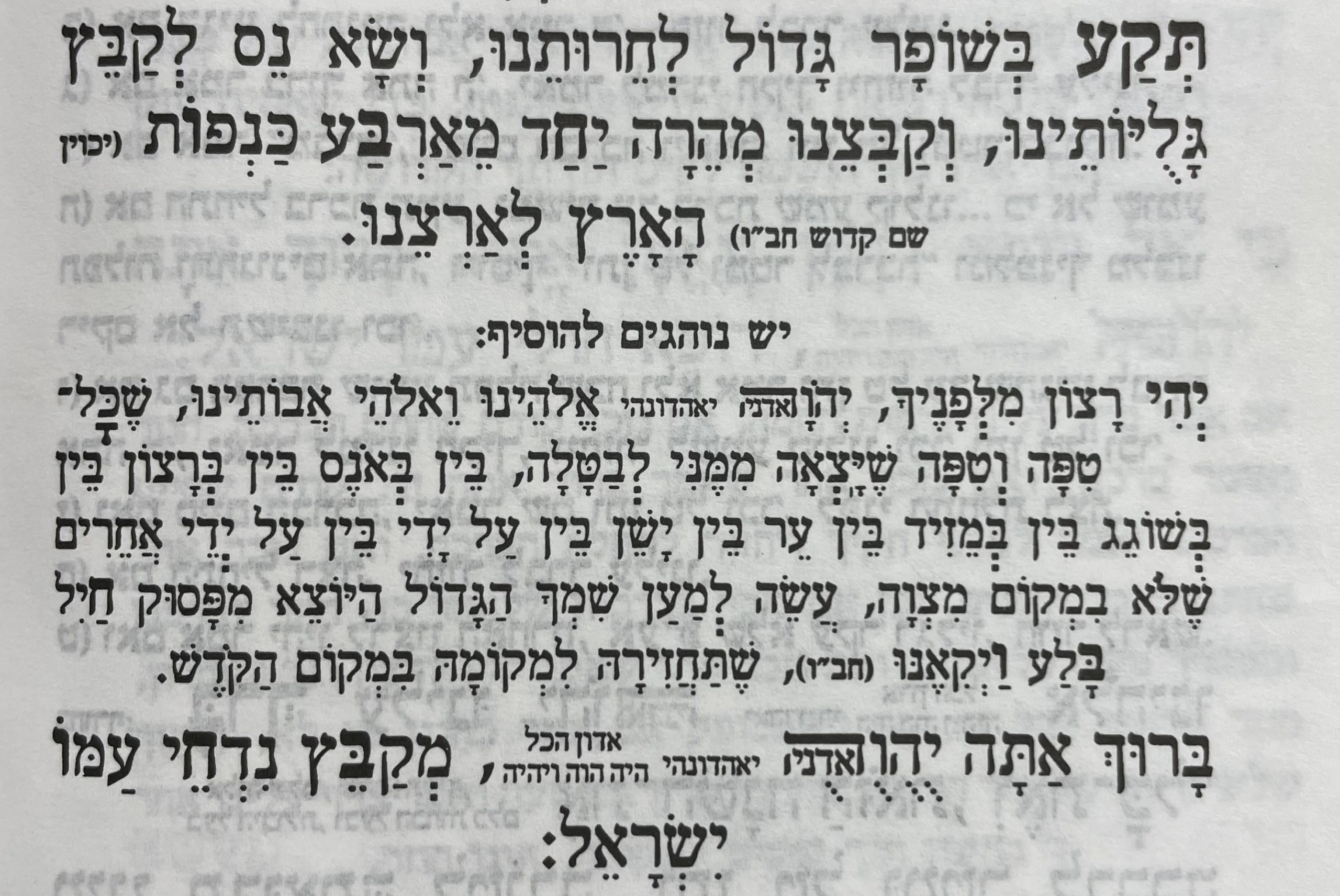

Finally, the last word for a serpent in Tanakh is ef’eh (אפעה), as we read in the Book of Job that “He sucks the head of a viper; the tongue of the ef’eh kills him.” (20:16) This one parallels the Sefirah of Yesod, the domain of sexual purity. In fact, the Kabbalists teach that of the 72 Names of God, the one that links to Yesod and through which one can atone for sexual sins is חב״ו. In the Amidah, there is a kavanah to insert during the kibbutz galuyot blessing to purify one of wasted seed and other sexual issues and it quotes a well-known phrase chayil bala’a vayakienu, mibitno yorishenu El, “The riches that he swallowed he vomits; God empties it out of his innards.” The letters of the first three words (חַיִל בָּלַע וַיְקִאֶנּוּ מִבִּטְנוֹ יֹרִשֶׁנּוּ אֵל) spell חב״ו. And where does this powerful verse come from? The preceding one in Job! (20:15) Thus, we have a clear Scriptural link between the ef’eh and Yesod.

Text of the blessing, with kavanah, both highlighting the חב״ו name.

And what of the Mochin, the upper three Sefirot? Perhaps we can link them to serpentine terms outside of Scripture. For instance, there’s the Teli (תלי) of Sefer Yetzirah (6:1-2), typically understood as the dragon constellation Draco. Recall that Sefer Yetzirah is an exposition of the Lamed-Bet Netivot Chokhmah, 32 Paths of Wisdom, so the Teli is directly linked to the Sefirah of Chokhmah. Then there’s the Talmud’s Aramaic hiviya (חויא), the root of which is said to come from Eve (חוה), and her encounter with the Snake. This would parallel the “motherly” Sefirah of Binah (also called Ima). And Keter on top, the origin of all the others, would be the generic term Tanin (תנין) with which we started, referring to any of the serpents below and often used interchangeably with them, as in this week’s parasha. Altogether, we have the following array of links between mystical Sefirot and mystical serpents: