This week’s parasha, Beshalach, describes the climax of the Exodus, the great Splitting of the Sea, following which Israel began its sojourn in the wilderness. We are introduced to an important geographical region, midbar Sin, the “Wilderness of Sin” (Exodus 16:1, 17:1). Presumably, this is where the name of Mount Sinai comes from. In the past, we have already explored the true location of Mount Sinai and the Sin Wilderness (which is not where the “Sinai Peninsula” is today, in Egypt).

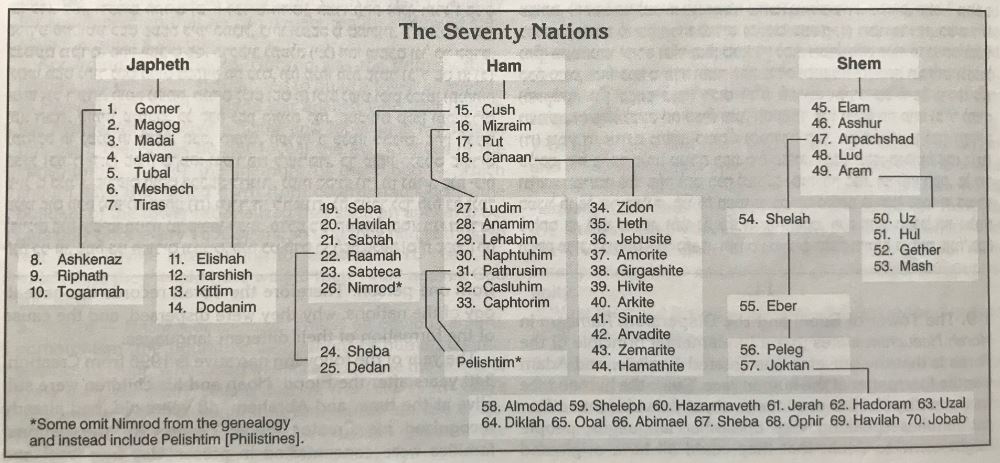

Sin does appear earlier in the Torah, in the “Table of Nations” that describes the 70 root nations that emerged from Noah and his three sons (Genesis 10). There we learn that the Sinites (Sini, סִּינִֽי) were descendants of Ham, through his son Canaan. Apparently, they were originally a subgroup of Canaanite! What’s more perplexing, however, is that today the term Sini refers to an East Asian person, and more specifically, a Chinese person. This is not just a Modern Hebrew appellation, but goes back at least to the time of the Rishonim. How did the Far East become associated with the ancient Wilderness of Sin?

A “Table of Nations” from the ArtScroll Stone Chumash

The First Shabbat

At first glance, it seems like China and the Far East make no appearance in the Torah. The simple explanation for this is that China was too far away to register on the radar of the Israelites. It would be irrelevant to discuss distant peoples who had no relationship with Israel. That said, we know that the Torah is eternal, the Word of God, and encodes all key aspects of human life within it. There is no way that the Torah does not, in some way, refer to the great peoples of the Far East, especially because they have played such an important role in human history. Today in particular, we recognize China as a global superpower that is instrumental on the world stage. Surely, the Torah (and our Sages) had something to say about this. Looking a little deeper, we find that this is, indeed, the case. In fact, China and the Far East are the subject of an intriguing halakhic discussion.

Our Sages taught that Israel is the centre point of the universe. Creation began with Even HaShetiya, the “Foundation Stone”, which lies beneath what is today the Dome of the Rock. From that initial point, the universe burst forth and expanded ever rapidly, eventually resulting in all that we have today (this expansion was first alluded to by our Sages in the Talmud, Chagigah 12a, and in much more depth in the Zohar). Thus, the events of Creation could be said to have first taken place in Israel, and spread outward from there. That being the case, the first Shabbat was surely marked in the Holy Land. Yet, that presents a huge problem:

As we all know, the sun “rises” in the East. It first appears there, and first sets there. So, our Sages asked, does that not mean that China should have experienced the first Shabbat before Israel?

One of the texts that goes into a deep philosophical discussion of this problem is the classic Kuzari. There, Rabbi Yehuda haLevi (1075-1141) passionately argues that Israel did experience Shabbat first. There are various ways to go about explaining it. The simplest is that, yes, the sun first rose up over China, even before it did over Israel, but Shabbat was still felt in Israel first: When it was the eve of Shabbat on Friday in Israel, China was already well into Saturday—but it was not Shabbat there. Since Shabbat was “created” in Israel, and when the first Shabbat began, China was already part way through Saturday, it could not have been Shabbat there. The following week, China did experience its first Shabbat—which was already Israel’s second Shabbat! In other words, the first Saturday in China was just a plain Saturday, and not a Shabbat Saturday!

An important thing to mention here is that Rabbi Yehuda haLevi spells Sin with a tzadi (צין or צן). However, the tzadi was pronounced as sa’adi in ancient times—and still today by many Sephardic and Mizrachi Jews—so there is no great difference in pronunciation between צין and סין. (See ‘Shabbat or Shabbos: What’s the Correct Pronunciation?’ in Garments of Light, Volume Two.) The Torah itself appears to use both spellings for the wilderness, for instance, in Numbers 13:21 and 20:1 it is spelled מדבר צן. To be fair, there is some debate regarding whether this is the same place as the מדבר סין in this week’s parasha.

In Numbers 33, where the entire itinerary of Israel’s forty years in the Wilderness is presented, we have three distinct places: מדבר סין, מדבר צן, and מדבר סיני. It is possible that they are all different areas within one large geographical region, or that they really are one place and Israel took circuitous routes returning to the same area, with the Torah varying the spelling deliberately to allude to deeper secrets. In Modern Hebrew, the צ is used to make a ch sound, too, so it is even more appropriate for Rabbi Yehuda to have used the צין spelling for “China”.

On that note, another vital point to mention is that when Rabbi Yehuda haLevi refers to Sin, he means the entire Far East, and not the current political entity of China. This must be said because, of course, Japan is even further east than China so Japan would have been first to usher in a Saturday. For the purposes of this discussion, all East Asian peoples—whose cultures strongly overlap—can be included within the ancient root nation of “Sin”.

So, how is it that the ancient Sinite of Genesis became the East Asian nations?

The Great Dispersion

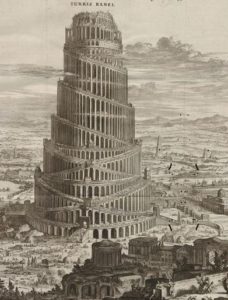

‘Turris Babel’ by Athanasius Kircher

After the Great Flood, Noah and his family repopulated the Earth. His three sons gave rise to the seventy root nations of the world. All of these seventy lived in a relatively confined geographical area within the Middle East. A couple of centuries later, when they were still not too numerous, were all still united, and still speaking one language, they undertook to built the infamous Tower of Babel. The result was that God dispersed the seventy families around the world, jumbled their languages into distinct ones, and only now, at this point, following the Great Dispersion, did the Earth have seventy distinct nations. Over time, these seventy split even further into the many nations and cultures we see today.

So, for instance, the family of Ashkenaz, a grandson of Yefet and one of the original seventy, was dispersed to Central Europe and gave rise to the various Germanic peoples. This is why Jews who ended up settling there millennia later became “Ashkenazi” Jews. The son of Ham named Mitzrayim had his family dispersed to the area we now know as Egypt. In this fashion, it appears that the family of the original Sin, great-grandson of Noah, was dispersed to the Far East. They were the first to inhabit the area where Israel later sojourned following the Exodus, so the Torah retains the authentic place name of midbar Sin. However, the spiritual descendants of the ancient Sinites are today the peoples of the Far East. And, chief among them, is China.

There is something of a compliment in connecting China to the Sin Wilderness, where God revealed Himself and gave His Torah to the people of Israel. Nothing is a coincidence, so what is the spiritual connection between Israel and China? We find that there actually is an impressive link, and that one of the key ideas and practices that is absolutely central to the Jewish people is also central for the Chinese.

The Lunisolar Calendar

While the secular world follows a solar calendar of 365 days, and many other nations follow a lunar calendar of roughly 354 days (including Muslims and most ancient peoples), Israel is unique in following a lunisolar calendar. We have lunar months, resulting in lunar years, but seven times in 19 years we add an entire month to realign with the sun. So, over a 19-year period our calendar is also solar. The Jewish calendar is fundamental to our Torah lifestyle, and informs every moment of our lives. It is so important that it was actually the first mitzvah God gave to the Jewish people in Egypt! (Exodus 12:2) With that in mind, it is amazing to consider that Jews are not the only nation today who follow such a calendar—the Chinese do, too!

The Chinese calendar consists of twelve lunar months, each of which is also either 29 or 30 days like ours. And like us, they add leap months to realign with the sun. This ensures that Chinese New Year always falls some time at the end of January or start of February, just like we add leap months to ensure that Pesach always fall at the end of March or start of April (to kick off spring). Moreover, they have a 19-year cycle with seven leap months in between, just as we do! In short, the Jews and the Chinese basically use the same calendar system. (The Chinese calendar is used by many in the Far East, with slight variants in Korea, Vietnam, and Japan—which officially abolished its use only in 1873.)

It goes further. For centuries, Jews have derived meaning from our calendar years. The numerical value of the year is given a siman of some sort, where the gematria of the year has a meaning, or the letters that make it up are an acronym that stands for something. For instance, Rav Yitzchak Ginsburgh has this year (תשפג) standing for תְּהֵא שְׁנַת פֶּלֶא גָּדוֹל, “may it be a year of great wonder!” The Chinese also derive meanings from their new years. Most famously, they do this through the Chinese Zodiac, with every year representing the qualities of a particular animal. This year, 4721 on the Chinese calendar, is the Year of the Rabbit. (It is interesting to note that 4721 means their calendar began when the Hebrew year was already 1062, which is shortly after Noah was born, his birthyear according to Jewish tradition being the year 1056 AM.) Here, we find another amazing connection to Judaism.

Year of the Snake

Our Sages taught that civilization, as we know it, will last no more than 6000 years (see Sanhedrin 97a and Avodah Zarah 9a). Mashiach must come before that time to usher in the final era of mankind, and the “Great Sabbath”, the seventh millennium. Each “day” corresponds to a millennium of human history. As explored in the past here, our Sages also taught that one starts to prepare for Shabbat on Friday afternoon, six hours before the onset of the Sabbath. So, if each “day” on the cosmic clock corresponds to a millennium, then each “quarter-day” of six hours is 250 years. According to this famous calculation, the time to start “preparing” for the final millennium, the Great Shabbat, is 250 years prior. This brings us to the Jewish year 5750, which began in September of 1989.

This date is considered the final possible start time to the Ikvot haMashiach, the “Footsteps of the Messiah”. Indeed, that year was monumental in human history: just weeks after Rosh Hashanah 5750, the Berlin Wall came down to end the Cold War and unravel the Soviet Union. A month later, Tim Berners-Lee proposed the creation of the World Wide Web, planting the seeds for the internet revolution that has totally transformed every aspect of life. That year also saw the start of the Human Genome Project and the launch of the first GPS satellite into space. It was around that time that China experienced its first tremors in the Tiananmen Square protests, leading directly to China opening up to the rest of the world and shifting gears away from communism towards capitalism. It was truly then in 1989 that the “sleeping dragon” that is China was awakened, and only since then that China has been able to develop into a global superpower.

Chinese Zodiac (Credit: PowerofPositivity.com)

On the Chinese calendar, that year happened to be the Year of the Snake. This is of tremendous significance. As discussed here, and more recently here, the snake is the key symbol of Mashiach. The gematria of Mashiach (משיח) itself, 358, is equal to nachash (נחש), “snake”. The symbolism originally stems from Jacob’s blessing to his son Dan, where he expressed his hope for salvation, and secretly described Mashiach as a “snake upon the road, a viper upon the path, that bites the horse’s heel…” (Genesis 49:17-18) Fittingly, the year following the Snake on the Chinese calendar is the Year of the Horse! And right before the Snake is the Year of the Dragon, in Hebrew the Leviathan, the great serpentine beast that Mashiach is supposed to subdue and slay at the End of Days. And so, the Chinese calendar provides just one more siman to the notion that we are firmly in the preamble to the Messianic age.

To bring it all together, when our Sages spoke about whether the first Shabbat was in Israel or in China, I believe there was a secret prophetic clue embedded there, alluding to the final Great Shabbat, the seventh millennium, and the serpentine signs of its approach. I believe our Sages knew that the East Asians, those people of Sin, also followed a lunisolar calendar like ours, and if anyone has a claim to the use of divine time, it is only our two peoples. In this light, the argument over the first Shabbat is all the more significant.

Sleeping Dragon

Today, Israel and China have an almost paradoxical relationship. On the one hand, China has been a huge investor in Israel, building some of its ports and railways, buying out nostalgically-Israeli entities like Tnuva, and even giving a whopping $130 million donation to Haifa’s Technion in 2013. On the other hand, China has been critical of Israel on the world stage, and has supported its archenemies, chief among them Iran. At the same time, China is Israel’s largest trading partner, while Israel is China’s second-largest arms supplier (after Russia). Ben-Gurion foresaw that China would be a global superpower one day, and he made Israel the first country in the Middle East to recognize the People’s Republic of China in 1950.

Chinese Jews from the ancient Jewish community of Kaifeng. Some consider the Kaifeng Jews to be one of the lost Tribes of Israel.

It is critical to distinguish here between the People’s Republic of China, and the good people of China. In China, books about Jews have become increasingly popular, and many Chinese see Jews as role models, and hope to emulate Jewish success.* There is also a great deal of overlap in Chinese traditions and Jewish traditions, among them conservative values and strong family ties, the importance of remembering and commemorating ancestors, and the primacy of study and education. So, there’s definitely an opportunity to build even stronger ties going forward. That said, Israel finds itself in a very difficult position trying to maintain good relations and please both the United States and China, stuck in the middle of a new “cold war” between the two powers.

It remains to be seen what the future holds for modern China and modern Israel, whether the dictatorial People’s Republic can really be trusted, and what role China will play in the sequence of events at the prophesied End of Days. Is there a connection between the dragon Leviathan that Mashiach must subdue, and the superpower whose greatest symbol is the dragon? If Ezekiel 30:15 is any indication (“I will pour my wrath upon Sin…”), the future might not be so rosy.

Shabbat Shalom!

*Years ago, I tutored a Chinese student (in science) and noticed on his desk a book in Chinese with a star of David on the cover. I asked him about it and he said it describes how Jews control the world. I explained to him that this is an antisemitic conspiracy and not actually true. His reply was something along the lines of that he hopes it is true, because the book’s message is that Jews are so great and the Chinese should be like them! He knew I was Jewish, of course, so he actually meant it as a compliment, and wanted to show me that he wants to emulate his teacher!

Pingback: Chinese Zodiac in Judaism | Mayim Achronim