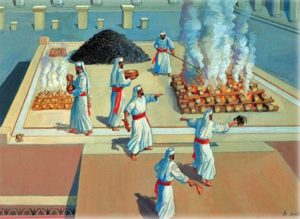

Offerings on the Altar (Courtesy: Temple Institute)

This week’s Torah reading is Acharei, focusing on the details of the priestly procedure performed on Yom Kippur in the Temple (or Tabernacle). God instructs Aaron to take two goats and one bull. One of the goats is to be sacrificed, while the other is to be sent to “Azazel” (the identity of which we have discussed in the past). Meanwhile, the bull is also to be sacrificed, and its blood sprinkled on the Holy Vessels within the innermost chamber of the Temple, the Holy of Holies. The third book of the Torah, Vayikra (Leviticus), often details such lengthy sacrificial procedures. To the modern reader, these passages tend to be quite difficult to read, with rituals that seem unnecessarily bloody and distasteful. Does God really want us to sacrifice animals? And when the Third Temple is rebuilt, will we once again be responsible for performing such rituals?

Back to the Garden of Eden

When God initially created the world, he placed man in a perfect environment where there was absolutely no death or bloodshed of any kind. Man was instructed only to consume fruits and plant matter. In fact, it wasn’t until the time of Noach that God reluctantly agreed to allow mankind to consume meat.

From a Kabbalistic perspective, this was done only for the purposes of tikkun, spiritual rectification (see Sha’ar HaMitzvot on parashat Ekev, and Sha’ar HaPesukim on Beresheet). The sinful souls of the flood generation were reincarnated into animals, and through their slaughter and consumption, those souls could be rectified and returned to the Heavenly domain. This is clearly hinted to in the phrasing of the Torah’s text: the animals that Noach took unto the Ark to be saved were initially described as zachar v’nekeva, “male and female” (Genesis 6:19). However, we are later told that some of the animals, particularly those to be slaughtered following the flood, were ish v’ishto, literally “man and woman”, or “husband and wife” (Genesis 7:2)!

We can deduce from this that sacrifices—and the consumption of meat in general—is a temporary phenomenon, for the purposes of tikkun, and not what God intended in His ideal conception of the world. Indeed, God often states in Scripture that He neither wants, nor requires, any sacrifices. He even states, perplexingly, that He never commanded them to begin with:

So said Hashem, Lord of Hosts, the God of Israel: “You add burnt offerings onto your sacrifices, and eat flesh, which I did not speak unto your forefathers, nor did I command them on the day that I took them out of Egypt, concerning burnt offerings and sacrifices. Rather, it is this that I commanded them: Listen to My voice, and I shall be for you a God, and you shall be for me a people, and you shall walk in all my ways that I shall command you, that it may be well for you.” (Jeremiah 7:21-23)

The Rambam explains that when taking the Israelites out of Egypt, God could not forbid them from offering sacrifices. This is because in that time period, offering sacrifices was the most common form of divine worship among the masses, and this is what the Israelites were familiar with. Thus, God allow the Israelites to bring sacrifices temporarily, as a means to slowly wean them off the practice:

The Israelites were commanded to devote themselves to His service… But the custom which was in those days general among all men, and the general mode of worship in which the Israelites were brought up, consisted in sacrificing animals in those temples which contained certain images, to bow down to those images, and to bum incense before them; religious and ascetic persons were in those days the persons that were devoted to the service in the temples erected to the stars, as has been explained by us. It was in accordance with the wisdom and plan of God, as displayed in the whole of Creation, that He did not command us to give up and to discontinue all these manners of service; for to obey such a commandment it would have been contrary to the nature of man, who generally cleaves to that which he is used to; it would in those days have made the same impression as a prophet would make at present if he called us to the service of God and told us in His name, that we should not pray to Him, not fast, not seek His help in time of trouble; that we should serve Him in thought, and not by any action. For this reason God allowed these kinds of service to continue; He transferred to His service that which had formerly served as a worship of created beings, and of things imaginary and unreal, and commanded us to serve Him in the same manner; namely, to build unto Him a temple; “And they shall make unto me a sanctuary” (Exodus 25:8); to have the altar erected to His name; “An altar of earth you shall make me” (Exodus 20:21); to offer the sacrifices to Him; “If any man of you bring an offering unto the Lord” (Leviticus 1:2), to bow down to Him and to bum incense before Him… By this Divine plan it was affected that the traces of idolatry were blotted out, and the truly great principle of our faith, the Existence and Unity of God, was firmly established. This result was thus obtained without deterring or confusing the minds of the people by the abolition of the service to which they were accustomed and which alone was familiar to them…

The Rambam goes on to elaborate on this point in more detail, and to thoroughly prove his argument, which is quite a fascinating read (Guide for the Perplexed, Part III, Ch. 32). He is clear on the fact that sacrifices were not God’s original intention, as we see in the Garden of Eden and through the words of the Prophet Jeremiah, but only a temporary necessity.

Sacrifices in the Third Temple?

Having said that, the Rambam does, somewhat paradoxically, write in his Mishneh Torah that sacrifices will resume in the Third Temple. It appears that the Rambam publicly went with the mainstream Orthodox approach but, in private, held that sacrifices will not be performed ever again. The Rambam writes that prayer is a far greater mode of worship than sacrifice, an idea that goes back to the prophet Hoshea, who declared “…we shall offer the cows with our lips.” (Hoshea 14:3)

More recently, Rabbi Avraham Itzchak Kook, the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Israel, similarly appeared to vacillate on the issue. In one place, he suggests that only grain offerings will be reinstated, and not animal offerings. (This is based on Malachi 3:4, which only mentions a restoration of grain offerings.) The Midrash suggests that only one type of offering will return, the voluntary Todah, or “thanksgiving” offering (see Vayikra Rabbah 9:7). Others propose that sacrifices will return for a short period of time only before being permanently abolished.

Ultimately, if God intended a perfect world with no death—as was His original plan for the Garden of Eden—and the future Redemption is essentially a global return to a state of Eden, then we certainly shouldn’t expect any more (animal) sacrifices in the future. It should be mentioned that the Sages teach that Adam did bring an animal sacrifice to God (Avodah Zarah 8a). However, this was not inside the Garden of Eden, but after he had already been banished, and due to his fear that the previously-decreed death sentence was upon him. Within Eden itself there could not be any death whatsoever. And so, if the world is set to return to an idyllic Eden-like state, there will certainly be no place for sacrifices.

The above is adapted from Garments of Light, Volume Two. Get the book here!