This week’s parasha, Beshalach, recounts the Splitting of the Sea. It is common knowledge that this was the Red Sea, called yam suf in Hebrew. Yet, in recent decades scholars have tried to “debunk” that notion, preferring to associate yam suf with a smaller lake of some sort. They often start by pointing out that yam suf literally means “sea of reeds”. It is the Reed Sea, not the Red Sea. There are indeed several shallow, marshy lakes with reeds in that vicinity of Egypt, around the modern Suez Canal. The fact that the Torah speaks of the “Reed Sea” being near places like Pi-Hahirot, whose location is believed to be known, is used as further proof of yam suf not being the Red Sea.

Of course, this serves to diminish the great miracle of the Splitting of the Sea. It almost implies that the Israelites waded through a shallow lake, as opposed to crossing a vast expanse. The reality is that such a hypothesis does not at all fit with the descriptions we receive in the Torah. A careful look reveals what yam suf actually is, and further helps to locate an even bigger prize: Mount Sinai.

A Sea or a Lake?

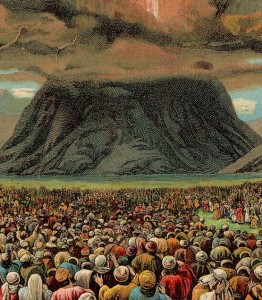

From the Torah’s description of the Splitting of the Sea, we learn that the waters stood as large walls to the left and right of the Israelites, and that the Egyptians later drowned in its depths (see, for instance, Exodus 14:28-29, 15:4, 8). This implies a deep sea, not a shallow, marshy lake.

Yam suf is mentioned well over twenty times in the Tanakh. When going through these verses and their context, one will find that it is a major geographical entity, not a small lake. For example, Numbers 14:25 says that the Amalekites and Canaanites live near yam suf, while Numbers 21:4 says the Edomites are near it, too. If it was a small lake somewhere in the Sinai Peninsula, or by the Suez Canal, this wouldn’t make much sense.

In fact, the land of Edom is known to be in the area of what is today the Negev desert, roughly southern Israel and Jordan, going down to what is today Eilat. This is confirmed by I Kings 9:26, where we read that “King Solomon made a navy of ships in Etzion-Geber, which is beside Elot, on the shore of yam suf, in the land of Edom.” King Solomon built a navy-yard in a port near Elot (אֵלוֹת), undoubtedly related to today’s Eilat. And, like today’s Eilat, is in on the shore of yam suf, the Red Sea, in the land of Edom. This verse solves the entire puzzle. Scholars wonder why the sea became known as the Red Sea, when the answer might be right there in the Torah: to the Israelites, this was the sea by the land of Edom, which literally means “red”. It was the Edomite Sea, the “Red Sea”. And it is the selfsame body of water as yam suf.

On that note, some have proposed that is isn’t yam suf, but yam sof, literally the sea “at the end”, since it is at the southernmost tip of Israel. Yet another idea is that it is yam sufa, “Storm Sea”, referring to the great wind storm that God sent to part the waters (Exodus 14:21). Whatever the case, there is little doubt that the Israelites did indeed cross what we know today as the Red Sea.

The bigger question is: where exactly did they cross?

Some believe that the Red Sea got its name from the red blooms of sea sawdust, Trichodesmium erythraeum (a type of cyanobacteria), that occasionally happen there.

Sinai or Saudi Arabia?

It is commonly thought that Mount Sinai is somewhere in what is today called the Sinai Peninsula. In fact, back in the 6th century, Christians built a monastery on a mountain in the Peninsula which they believed to be Sinai. It still operates today as Saint Catherine’s Monastery, and is among the oldest Christian monasteries in the world. The only problem is that it isn’t anywhere near the real Mt. Sinai.

First off, the Torah introduces us to Mount Sinai when Moses is living far from Egypt in Midian. Recall that Moses had fled Egypt, and eventually ended up living among the Bedouins of Midian… This already confirms that Mount Sinai was probably not in today’s Sinai Peninsula, which would have still been under Egyptian control in those days. In fact, we know from historical and archaeological evidence that in those days, the Egyptians ruled at least as far as Canaan itself. Moses fled outside of Egypt’s domain, across the Red Sea, to what is today Saudi Arabia. This is the land traditionally associated with the Midianites. And the Torah tells us that Mt. Sinai is there (Exodus 3:1-2):

And Moses was shepherding the flock of Jethro, his father-in-law, the priest of Midian; and he led the flock to the farthest end of the wilderness, and came to the mountain of God, unto Horev. And the angel of God appeared unto him in a flame of fire out of the midst of a bush; and he looked, and, behold, the bush burned with fire, and the bush was not consumed…

The Torah famously tells us that Moses saw a burning bush during his first encounter on the “mountain of God”. In Hebrew, it is called a s’neh, which gives rise to the name Mount Sinai. This mountain is in the wilderness around Midian, in a land call Horev. Later on, the Israelites cross the Red Sea and journey towards this same mountain, where they receive the Ten Commandments. This implies that the Israelites crossed somewhere in the Gulf of Aqaba, ending up in what is today Saudi Arabia. This makes all the more sense since they can journey from there to the wilderness “on the other side of the Jordan”, where they spent forty years before crossing the Jordan River—from the East—into Israel.

Amazingly, there is a mountain in Saudi Arabia which is completely sealed off by the authorities, and off limits to any historians or archaeologists…

The above is an excerpt from Garments of Light, Volume Two. To continue reading, get the book here!