In this week’s parasha, Ki Tisa, God commands Moses to make the special incense mixture of Ketoret. This was the highest and holiest service performed in the Temple. Once a year, on Yom Kippur, the kohen gadol would take three handfuls of this incense into the Holy of Holies. When the room filled with the incense smoke, the kohen would see a vision of God and thereafter procure atonement for Israel. Later in the Book of Numbers we see how the incense prevented a plague and saved countless lives following Korach’s rebellion. Based on this, the Zohar (II, 218b) teaches that in lieu of the Temple Ketoret, one can read the verses that describe the incense and this itself can ward off illness. This is why the Ketoret passage is found at the start of every siddur, and customarily recited before the daily morning and afternoon prayers.

Galbanum flowers

What exactly were the ingredients of this enigmatic mixture? The Torah seems to suggest that Ketoret had four spices: “God said to Moses: take for yourself spices, nataf and shechelet and galbanum; spices, and pure frankincense—an equal part each.” (Exodus 30:34) The Sages famously derive from this verse that Ketoret actually had eleven ingredients (Keritot 6a-b): first God said “spices”, implying two spices, then He listed three more (nataf, shechelet, galbanum), bringing the total to five altogether, and then the Torah strangely says “spices” again, implying that one should double the existing five, making ten, before adding “frankincense” for a total of eleven. These eleven ingredients were:

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: פִּיטּוּם הַקְּטֹרֶת: הַצֳּרִי, וְהַצִּיפּוֹרֶן, וְהַחֶלְבְּנָה, וְהַלְּבוֹנָה – מִשְׁקַל שִׁבְעִים שֶׁל שִׁבְעִים מָנָה. מוֹר, וּקְצִיעָה, שִׁיבּוֹלֶת נֵרְדְּ, וְכַרְכּוֹם – מִשְׁקָל שִׁשָּׁה עָשָׂר שֶׁל שִׁשָּׁה עָשָׂר מָנֶה. הַקּוֹשְׁטְ – שְׁנֵים עָשָׂר, קִילּוּפָה – שְׁלֹשָׁה, וְקִנָּמוֹן – תִּשְׁעָה. בּוֹרִית כַּרְשִׁינָה – תִּשְׁעָה קַבִּין, יֵין קַפְרִיסִין – סְאִין תְּלָתָא קַבִּין תְּלָתָא. אִם אֵין לוֹ יֵין קַפְרִיסִין מֵבִיא חֲמַר חִיוַּרְיָין עַתִּיק. מֶלַח סְדוֹמִית – רוֹבַע. מַעֲלֵה עָשָׁן – כׇּל שֶׁהוּא. רַבִּי נָתָן אוֹמֵר: אַף כִּיפַּת הַיַּרְדֵּן כׇּל שֶׁהוּא.

Our Sages taught: The blending of the incense: balm [tzori], and onycha [tzipporen], and galbanum, and frankincense, seventy maneh by mass. Myrrh, and cassia, and spikenard, and saffron [kharkom], sixteen maneh by mass. Costus, twelve maneh; aromatic bark [kilufah] three maneh; and nine maneh of cinnamon. Lye of Carshinah, a volume of nine kabin; Cyprus wine of the volume of three se’ah and three more kabin. If one does not have Cyprus wine, he brings old white wine. Sodomite salt, a quarter-kav. A minimal amount of the “smoke-raiser” [ma’aleh ‘ashan]. Rabbi Natan says: Also a minimal amount of Jordan amber.

We have 11 spices and herbs, plus another five ingredients to strengthen and perfect the mixture. The first one is nataf, literally “drops”, which is the first in the Torah’s list in this week’s parasha. Rashi comments that this is a certain type of “gum” resin. It is a balm that exudes from trees, possibly from myrrh. Some identify it with the “Balm of Gilead” (which has also been identified with the afarsamon of the anointing oil). It may be the Commiphora opobalsamum species of myrrh which is found growing around the Red Sea. Nataf is also translated as “stacte”.

The second in the Torah’s list is shechelet, and when our Sages first translated the Torah into Greek (the Septuagint) they used the Greek word onycha, literally a “fingernail”. This is why shechelet is called tzipporen (“fingernail”) in the Talmud. It was compared to nails probably because it was made from crushed sea snails and sea shells, including those of the Murex genus. This is significant because we know that the blue tekhelet dye—derived from Murex shells—was used extensively in ancient times (and to this day in dying tzitzit, as the Torah instructs). It makes perfect sense that the Israelites would extract the dye, and then use the shells for the incense. A further clue comes from the Talmud above, which goes on to say that “Carshinah lye”* (a strong chemical base containing sodium hydroxide) was used to “soften” the tzipporen, while Cyprus wine was used to help extract its fragrance. This seems to confirm that tzipporen comes from hard snail shells. However, others dispute this notion because the snails are not kosher animals.

The Talmud (Keritot 6b) suggests that onycha does grow from the ground, though it is not a tree. In fact, the Talmud asks why the Torah didn’t just list all 11 ingredients itself, and only mentioned four types? The answer is that God gave us the main categories of spices and herbs that may be used: nataf comes from trees, onycha comes from the ground (but is not a tree), and galbanum has a foul smell, while frankincense has an odour that diffuses but doesn’t produce smoke that rises up. Thus, we are given the general categories of ingredients: those derived from trees, those that are herbs, foul-smelling ones, and “essential oils” that diffuse but don’t smoke.

Galbanum has a bitter, “musky”, and turpentine odour. Rashi says (on Exodus 30:34) that we include it to remember the sinners of Israel, and that we shouldn’t lose hope and abandon them. The Ketoret represents all of Israel, and atones for all types of Jews. In fact, the Arizal taught that 11 is a number that symbolizes kelipah, the “husks” that cover up and conceal the sparks of holiness. Ten is a number that stands for wholeness and completion, just as we have Ten Sefirot, Ten Commandments, Ten Utterances of Creation, and so on. Eleven is one more than ten, like a covering over top, a husk to conceal the wholeness. The Ketoret thus neutralizes the kelipot, and rectifies all Ten Sefirot.

Each member of the Jewish people is spiritually rooted in one of the Sefirot, so the Ketoret is able to purify us all. At the same time, the entire people of Israel as a whole are rooted in the Sefirah of Tiferet. This Sefirah is associated with the sun, and the Zohar and Arizal teach that there are 365 lights which emerge out of Tiferet. These fittingly correspond to the 365 days of the solar year. And this is why the Ketoret was specifically prepared in a “solar” manner, with a total of 368 portions: the first four spices with 70 portions (making 280 total), the next four with 16 portions (making 64 total), then 12, 3, and 9 portions for the remaining ingredients, making 368 portions altogether. Of these, our Sages say “365 handfuls correspond to the days of the solar year, and the remaining three that the kohen gadol would bring into [the Holy of Holies] on Yom Kippur.” (Keritot 6a)

Psychoactive and Psychedelic Compounds

The fourth ingredient in the Torah and Talmud’s list is classic frankincense, also known as olibanum, from the Boswellia genus of trees. It has been used in healing and religious rituals for millennia, and still used today (often as an essential oil, like the Talmud states above). Recent scientific studies have confirmed that frankincense is both antimicrobial and neuroprotective. Similarly, the next ingredient myrrh has historically been used as an antiseptic and as a pain-killer. Recent studies show that chemicals in myrrh can affect the brain’s opioid pathway.

Interestingly, myrrh is featured prominently in the Purim story, both with Esther being bathed in myrrh (Esther 2:12), and with Mordechai’s name being derived from mira or mara dachya, “pure myrrh” (Chullin 139b). The latter is based on the Aramaic translation of Exodus 30:23 in this week’s parasha, which describes the production of the special anointing oil used in the Temple, for priests, and for kings. The recipe for this oil was simpler than the Ketoret, with three ingredients: 500 parts mor dror, literally “myrrh of freedom” (though translated as “pure myrrh” or “solidified myrrh”), then 250 parts cinnamon, and 250 parts of a mysterious kneh bosem, “aromatic cane”. Multiple commentators suggest that the myrrh here is actually musk derived from animals, but others reject this and maintain that it is regular myrrh from trees.

A hemp field in France

The last of the ingredients, kneh bosem, sounds very similar to cannabis. Though no major rabbinic sources say so, some academics have proposed that the unknown etymology of “cannabis” is actually the Torah’s kneh bosem (and the Sumerian kunibu). Cannabis has many known therapeutic properties, along with its hallucinogenic ones, so it wouldn’t be odd that it was used in the Temple’s spiritual services. Indeed, archaeologists have found chemical traces of CBD and THC (the active compounds in cannabis) on ancient Judean altars dating back to at least 2700 BCE. Cannabis is also the origin of the word canvas, for the same hemp plant was historically widely used to make clothing, mesh, and sacs. The Mishnah even mentions it in a discussion of kilayim, and whether one is permitted to mix together pishtan v’hakanebos, “wool and cannabis” (Kilayim 9:1).

Next there’s cassia, which is really just a type of cinnamon, the last ingredient in the list. Cinnamon is known to have some antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, and a recent study found that cinnamon might act like a “brain booster”, improving the use of glucose by neurons (and making rodents just a little bit smarter).

Turmeric flower

The Talmud’s kharkom is translated by the Rambam (Hilkhot Klei haMikdash 2:4) as saffron, made from the Crocus sativus flower. That said, there may be a better identification for it. Kharkom sounds a lot like curcumin from the Curcuma longa plant (better known as turmeric). Archaeologists have found curcumin in Israel going all the way back to the end of the second millennium BCE, so it would have definitely been known to the ancient Israelites. Curcumin, too, is well-known for its medicinal properties, and studies show that it even has powerful antidepressant effects (by inhibiting the enzyme MAO, monoamine oxidase, as many antidepressant drugs do). Substances in turmeric appear to be involved in the body’s cannabinoid system as well. In fact, cassia, cinnamon, and saffron all have traces of alpha-curcumene, one of the key active ingredients in turmeric. (Both saffron and curcumin have been used to make an orange dye; the saffron dye is the similar-sounding crocin).

Agarwood

The oils of spikenard were historically used for healing, especially as sedatives. (Spikenard is related to the better-known valerian family of plants.) Costus, too, was used extensively in ancient medicines to help treat everything from cancer to leprosy. The last ingredient of Ketoret is the mysterious kilufa, some kind of aromatic “bark” or “peel”. Rashi seems to say it is also a type of cinnamon. Rambam identifies it with the Arabic oud, which is agarwood or aloeswood. It may be the same as the ohalim trees mentioned in Tanakh (such as in Numbers 24:6 and Psalm 45:9). Agarwood and oud oils are highly prized for their aromas, and are therapeutic and psychoactive. Today, agarwood is considered the most expensive tree in the world, with pure agarwood going for as much as $100,000 per kilogram!

The Talmud then lists five more ingredients which were used to enhance the Ketoret mixture. We already noted that the Carshina lye and the Cyprus wine were used to soften and extract the compounds from the hard tzipporen onycha. Why did the latter specifically have to be Cyprus wine? Intriguingly, archaeologists have found multiple jugs of Cyprus wine in Israel, and what’s unique about them is that their remains contain traces of opium! Perhaps Cyprus wine was particularly prized and imported from across the sea because of its opium-enhanced psychedelic effects.

Similar to Carshina lye, we know that salt helps to extract the flavours and juices out of foods, hence the addition of melach sdomit, “Sodomite salt”. As explored at length in Secrets of the Last Waters, our Sages called it “Sodomite” salt specifically because it would atone for the grave sins and negative qualities of Sodom, which sadly doom many societies and communities.

The most mysterious ingredient of all was the ma’aleh ‘ashan, some kind of plant that made the smoke of the Ketoret rise in a vertical column. In Second Temple times, only one family of kohanim knew how to properly prepare the Ketoret mixture, the House of Avtinas. However, they refused to divulge the secrets of the incense, so the Sages sent for Greek scientists from Alexandria to come and figure out the exact composition! (Yoma 38a) The Alexandrians were able to determine all of the ingredients, except ma’aleh ‘ashan. The Sages gave up on it, and the secrets of the Ketoret were lost with the destruction of the Temple and the end of the Avtinas family line. Rabbi Steinsaltz suggested that ma’aleh ‘ashan is the Indian khimp plant of the Leptadenia pyrotechnica species. This herb is known to be highly flammable and can give off sparks when burned (hence the name pyrotechnica), while also being used extensively in ancient times for its medicinal properties (especially as an antifungal and anti-worming agent).

Ambergris

Kipat hayarden, “Jordan amber”, is another mystery. Rashi says it’s a plant that grows along the banks of the Jordan River. Rambam identifies it in Arabic as inbar, which is ambergris. Ambergris, “grey amber” is a fragrant waxy secretion from the sperm whale that would wash up on shorelines. The main active compound, ambroxide, is still used in many perfumes today.

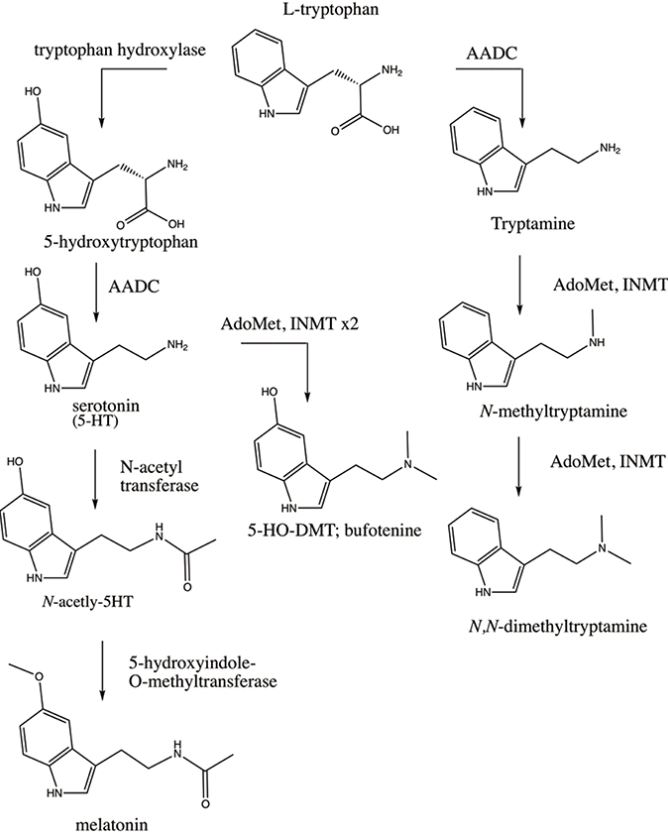

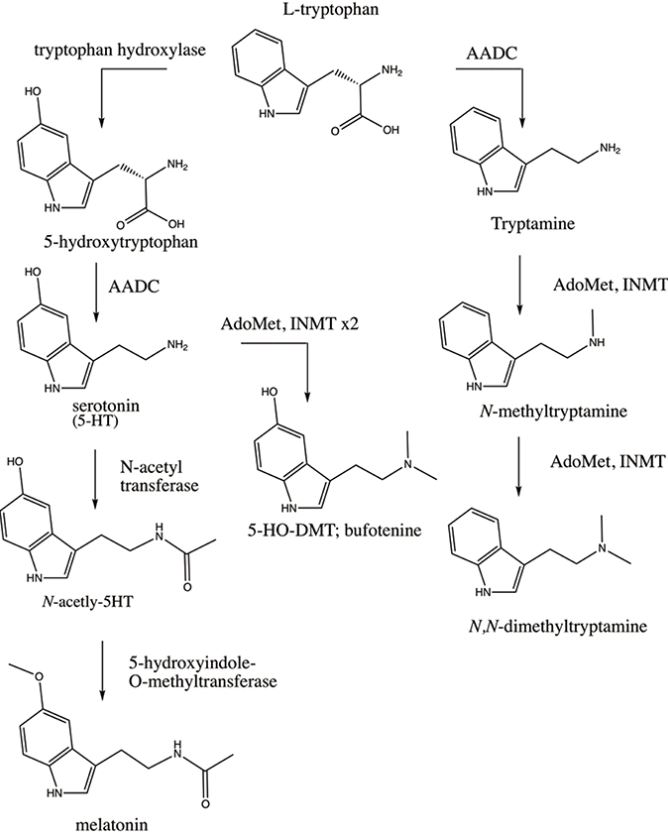

Finally, the coals used for burning the incense, and much of the wood used in the Mishkan, was ‘atzei shittim, acacia wood. Today we know that acacia wood is high in DMT. This is a hallucinogenic substance naturally produced by the pineal glands in our brains. The pineal gland regulates our circadian rhythm and produces melatonin to put us to sleep. Thus, there is good evidence that DMT (molecularly similar to melatonin, and made from the same animo acid) is involved in dreaming. It is also thought to play a role in prophetic visions, and much research has been done on this in recent decades. (We explored its connection to tefillin and wearing a kippah here.)

The production of melatonin and DMT (N,N-dimethyltryptamine) from the amino acid tryptophan.

Aside from their unique flavours, we find that the common denominator among many of these herbs and spices is that they are therapeutic, psychoactive, sedative, antidepressant, and maybe even hallucinogenic. With this in mind, it isn’t difficult to understand how the kohen gadol would get a profound spiritual vision when he entered the small Holy of Holies chamber and filled it with the smoke of the Ketoret. After all, many of the ingredients in the incense, as well as the anointing oil used to purify all the equipment (and the kohen himself), and even the wood of the Tabernacle and the wood on the altar, contained brain-stimulating and mind-altering compounds.

In fact, Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai teaches in the Zohar (III, 58b):

פָּתַח רִבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן וְדָרַשׁ, (שיר השירים א׳:ג׳) לְרֵיחַ שְׁמָנֶיךָ טוֹבִים וְגוֹ’. הַאי קְרָא אִסְתַּכַּלְנָא בֵּיהּ, וְהָכִי הוּא. לְרֵיחַ, מַאי רֵיחַ. רֵיחַ דִּקְטֹרֶת דְּאִיהוּ דְּקִיקָא וּמָעַלְיָא וּפְנִימָאָה מִכֹּלָּא, וְכַד סָלִיק הַהוּא רֵיחַ לְאִתְקַשְּׁרָא, בְּהַהוּא מְשַׁח רְבוּת דְּנַחֲלֵי מַבּוּעָא, אִתְּעֲרוּ דָּא בְּדָא וְאִתְקְטָרוּ כַּחֲדָא. וּכְדֵין אִינּוּן מִשְׁחָן טָבָאן לְאַנְהָרָא. כְּמָה דְאַתְּ אָמֵר, לְרֵיחַ שְׁמָנֶיךָ טוֹבִים

Rabbi Shimon opened the discussion saying: “Your ointments are good to smell…” (Song of Songs 1:3) I have closely studied this verse and this is the explanation: What is meant by “to smell”? This refers to the fragrance of the Ketoret, which is finer and elevates more than anything else. When this fragrance rises to join with the anointing oil of the fountain streams, they wake one another and connect together. Then these ointments are good for illumination, as the verse says, “Your ointments are good to smell.”

Clearly, there was something about the smell of the incense that “elevated” and “illuminated” a person. Moreover, the Zohar says in multiple places (such as III, 30b) that the ketoret had a stimulating effect, citing Proverbs 27:9 which says “Oil and incense gladden the heart” (shemen u’ketoret yismach lev, שֶׁמֶן וּקְטֹרֶת יְשַׂמַּח־לֵב). Note how the language of this verse is nearly identical to Psalms 104:15, which famously states “Wine gladdens the heart” (v’yayin ismach levav enosh, וְיַיִן יְשַׂמַּח לְבַב־אֱנוֹשׁ). There was indeed something about the ketoret which was intoxicating like wine, and the Zohar (III, 34a) even describes it as producing “a supernal joy both above and below” (וְחֶדְוָותָא דְּעִלָּאִין וְתַתָּאִין).

It’s worth remembering that the kohen gadol would only have this experience once a year, on Yom Kippur, after properly purifying himself, going to the mikveh multiple times, and on an empty stomach during a fast, after much prayer and meditation, and with great concentration and kavanah. Such substances should not be consumed frequently or lightly, nor should they ever be consumed simply for recreational purposes or as an “escape”. These are therapeutic and powerful “plant medicines”, ultimately meant for assisting in spiritual growth, healing, and enlightenment.

*The identity of Carshinah lye is quite mysterious. According to multiple opinions, it was actually a plant-based source, possibly the Bitter Vetch. In that case, it probably wouldn’t have sodium hydroxide in it, though it could be that the plant was used to produce potassium hydroxide. In old times, plants containing high amounts of potassium (or potassium carbonate) would be burned and then the ashes dissolved in water and boiled to produce lye.