This week’s parasha, Lech Lecha, begins with God’s command to Abraham to set forth out of Haran and settle in the Holy Land. Previously, we learned that Abraham was born in “Ur-Kasdim”, presumably the ancient city of Ur in Mesopotamia. “Kasdim” is commonly associated with the Chaldeans, who did not arrive onto the scene until long after Abraham. In fact, their founding ancestor, Kesed, was actually a nephew of Abraham! (See Genesis 22:22.) It is possible that by the time Moses was writing about the life of Abraham centuries later, the Kasdim were already a prominent group in Ur, so he could reasonably call it Ur-Kasdim. Alternatively, we can go with the explanation of our Sages that the term is not referring to a city at all, since ur kasdim can literally mean “flaming furnaces”. What is this referring to?

Recall that Abraham had been preaching monotheism and combatting the idolatry and immorality of his day, for which he was arrested by the first great Mesopotamian king, Nimrod. After ten years of imprisonment (Bava Batra 91a), Nimrod put Abraham on trial and told him to bow down to an idol or die. Abraham refused, and was thrown into the flames. It was then that God first revealed Himself to Abraham and miraculously saved him. This is the deeper meaning behind the statement that God took Abraham out of ur-kasdim (Genesis 15:7, Nehemiah 9:7), ie. out of the flaming furnaces. It also explains the Torah’s statement that Abraham’s brother Haran died in ur-kasdim (Genesis 11:28). He followed Abraham into the flames, but did not survive as he was not righteous. So, “Ur-Kasdim” is not referring to Abraham’s birthplace.

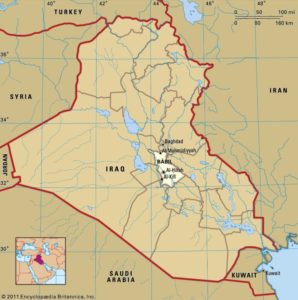

Where Abraham was born is not clear, but it was certainly somewhere in Mesopotamia (roughly modern-day Iraq), a region called Shinar in the Torah. Some hold that Shinar is a contraction of shnei nahar, between rivers, ie. Mesopotamia (which means “between rivers” in Greek), referring to the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. This is somewhat problematic because Shinar is spelled with a letter ‘ayin (ע), whereas nahar (“river”) has a hei (ה). According to the apocryphal Book of Jubilees, Shinar was the name of a person (see 10:18, for instance), perhaps the first to settle the area. The Shinar region was also known as Bavel, “Babylon”, especially after the later Neo-Babylonian Empire. This name comes from the ancient city of Bavel, where the infamous Tower of Babel was built. As punishment for their rebellion against the Heavens, God scattered the people and transformed them into many different nations with distinct languages. Since He balal, “confounded”, the languages there, it became known as Bavel.

Having said that, there is an alternate explanation for the name. The ancients that lived there called it Bab-Il or Bab-El, meaning “gate to God”. It later become Bab-Ilim, “gate to gods”, and possibly also Bab-Elyon (likely giving rise to “Babylon”), which literally means “gate to Above” or “gate to Heaven”. The ancients believed this was one of the unique places on the planet where Heaven and Earth met. It was a “stargate” of sorts, and that would explain why they sought to build the “tower” and launch their conquest of the Heavens from there. Those people knew ancient mystical secrets, and knew how to manipulate angels and various spiritual forces (see the Arizal’s Likkutei Torah on Noach). Our Sages even spoke of a migdal haporeach b’avir, a “tower that flies through the air” (see, for instance, Sanhedrin 106b, with Rashi). In short, the “Tower of Babel” was no simple tower! This is why God punished its builders by wiping their memory clean and confounding their languages, making them forget their mystical knowledge and angelic powers.

Having said that, there is an alternate explanation for the name. The ancients that lived there called it Bab-Il or Bab-El, meaning “gate to God”. It later become Bab-Ilim, “gate to gods”, and possibly also Bab-Elyon (likely giving rise to “Babylon”), which literally means “gate to Above” or “gate to Heaven”. The ancients believed this was one of the unique places on the planet where Heaven and Earth met. It was a “stargate” of sorts, and that would explain why they sought to build the “tower” and launch their conquest of the Heavens from there. Those people knew ancient mystical secrets, and knew how to manipulate angels and various spiritual forces (see the Arizal’s Likkutei Torah on Noach). Our Sages even spoke of a migdal haporeach b’avir, a “tower that flies through the air” (see, for instance, Sanhedrin 106b, with Rashi). In short, the “Tower of Babel” was no simple tower! This is why God punished its builders by wiping their memory clean and confounding their languages, making them forget their mystical knowledge and angelic powers.

Still, Babylon remained as a secret portal to the Heavens, much like Jerusalem. It is not a coincidence that Abraham received his first prophetic vision there, and it was there that the “Era of Torah” officially began: Our Sages state that human history unfolds over three 2000-year eras (Sanhedrin 97a): the first was the lawless era of “chaos”, then came the prophetic Era of Torah, followed by the last two millennia preparing for Mashiach. The Era of Torah began in the year 2000 AM, and it was precisely then that God first revealed Himself to Abraham, when He miraculously saved Abraham from the flames. Henceforth, Abraham began teaching God’s law. (Beforehand, he was spreading monotheism more generally.) He first settled in Haran, where he lived until he was 75 years old, where this week’s parasha begins.

Further on, we read about the War of the Kings, when Abraham took on four mighty Mesopotamian warlords (Genesis 14). Their leader was King Amraphel of Shinar. Rashi identifies him with the same old Nimrod who originally imprisoned Abraham and sought to execute him. As expected, his name had changed in the new and confused, post-Dispersion reality. (For more on this, see ‘Eye for an Eye: Abraham and Hammurabi’ in Garments of Light, Volume Two.) It seems that Nimrod was coming back for revenge, but Abraham prevailed once again. He continued his life of teaching for many decades to come, setting the foundations of Torah and Judaism.

The “Era of Torah” would last until the year 4000 AM (around 240 CE), by which point the Tanakh had been canonized, the Mishnah had been recorded, along with many of the key mystical texts like Sefer Yetzirah and the Heikhalot, the manuscripts that would later make up the Zohar, the earliest works of Midrash, and much of the Jerusalem Talmud. Around that time, Rav and Shmuel, two students of Rabbi Yehuda haNasi (the main author and editor of the Mishnah), returned to Babylonia and launched the composition of the Babylonian Talmud. Here, the whole Torah process comes full circle, having started in Babylon with Abraham, and now ending in that same place. [Perhaps there is a hint to this in the name Bavel (בבל), with beit being the first letter of the Torah and lamed being its last.]

It is important to note how the Sages insisted on calling it the Talmud Bavli, even though Babylon itself was long gone. At the time, they were living in the Sassanian (Persian) Empire, in cities like Pumbedita and Nehardea. Yet, it wasn’t called the Talmud Parsi, nor named after any of the cities where it was actually composed. It was named after ancient Bavel. Why? One answer offered by the Talmud itself is that the Talmud is “confused” and convoluted, mixing together all kinds of Scripture into a complex puzzle (Sanhedrin 24a). The Talmud is incredibly difficult to study, and an individual without a teacher or the support of oral tradition is unlikely to be able to penetrate it. The same Talmudic passage says that Bavel refers to a place of darkness and death. Babylon is not spoken of positively, neither in the Torah nor by our Sages. This negative association even extends to other religions, including Christianity and particularly Rastafarianism, where “Babylon” is a moniker for all things wicked and the root of evil. There is some truth to this.

Whereas Jerusalem is a “stargate” of sorts exclusively for angels, Babylon was seen as a “stargate” that was also used by the Sitra Achra, the realm of evil. In some ways, it is like the opposing counterpart to Jerusalem. In Babylon, the vernacular was Aramaic, which our Sages taught was the language of the “impure side”. As discussed in the past, Hebrew is a divine language, the language of angels. Aramaic, on the other hand, uses the exact same alphabet and sounds as Hebrew, but is employed by impure spirits. Angels speak Hebrew; impure spirits speak Aramaic. We pray in Hebrew so that the angels can take up our words to the Heavens. We recite Kaddish in Aramaic to repel the Sitra Achra, using their own language to praise God, thus driving them away (see Sha’ar HaKavanot on Kaddish). We study Mishnah in Hebrew to bring goodness into the world; we study Talmud in Aramaic to destroy evil. In fact, we refer to Talmud more commonly as Gemara (גמרא), which is said to stand for Gabriel, Michael, Raphael, and Uriel, the main guardian angels, which are empowered through its study.

For the same reasons, Midrash is in Hebrew, while the Zohar is in Aramaic. The Tanakh itself is nearly all in Hebrew, though there are lengthy passages in Aramaic, such as in the Book of Daniel. In short, we use Hebrew to bring in more purity and light, and we use Aramaic to fight impurity and repel darkness. Hebrew is Jerusalem, Aramaic is Babylon. So, we have two Talmuds: the Yerushalmi and the Bavli, Jerusalem and Babylon, the two supernal gates. In Jerusalem we bring light; in Babylon we dispel darkness. When comparing the two Talmuds, we find the Bavli peppered with discussions of magic and wizardry, angels and demons, whereas the Yerushalmi has nearly no such talk. In light of the above, we can understand why.

Historically, Jerusalem and Babylon were the two big centres of Judaism, and the places from which Jews sought to fulfil the mission of repairing the world and making it more Godly. That might help us further comprehend the Talmud’s statement that one should ideally live in Israel, and if not, then in Babylon (Ketubot 111a). The Babylonian region continued to play an important role in Judaism and Jewish history throughout the Geonic period (c. 6th-10th century CE), and into modern times. The city of Babylon gave way to Seleucia, and Seleucia to Ctesiphon, and Ctesiphon to Baghdad. It is estimated that in the 1930s, nearly 40% of Baghdad’s population was Jewish! The city gave rise to esteemed Jewish figures like the Ben Ish Chai and Sassoon Eskell, one of Iraq’s founding fathers. Following the tragic Farhud, and the anti-Semitic pogroms that followed Israel’s rebirth, nearly all of the Jews fled or were expelled. Today there are nearly none left.* And there is a spiritual reason for this, which may very well have been foreseen by the Zohar.

The Talmud (Sukkah 20a) notes that whenever “the Torah was forgotten from Israel” due to some catastrophe, someone would come from Babylon to restore it. The first such person was Ezra the Scribe. (The second was Hillel.) Ezra brought Torah back to Israel after the destruction of the First Temple by the Babylonians, led by Nebuchadnezzar. This evil king was, in turn, the reincarnation of Amraphel who, as noted above, was Nimrod, the first Babylonian tyrant (see Sefer Gilgulei Neshamot, letter נ). It appears Nimrod got his revenge after all! Of course, nothing happens without God’s supervision, and the prophet tells us that Nebuchadnezzar was God’s appointed servant, to punish Israel for their sins (Jeremiah 27:5-6). That does not absolve Nebuchadnezzar from responsibility, for God works it out in such a way that people who are already wicked are used as His agents, and are then themselves punished for their wickedness.

As such, the Zohar (II, 58b) explains that Nebuchadnezzar will have to return once more, at the End of Days, to lead Babylon against Israel yet again, and only then will he be defeated for good. What’s most amazing is that we may have witnessed this in our own lifetimes. Babylon is in modern-day Iraq, and Iraq had one famous megalomaniacal dictator who shook up the whole world: Saddam Hussein. At one point, his army was the fourth largest on the planet. Bizarrely, Saddam fully believed himself to be a new Nebuchadnezzar, so much so that he excavated the ruins of ancient Babylon and built himself a palace there, like Nebuchadnezzar’s. He sought to resurrect Babylon and make it the capital of his new empire.

A 1987 gold-plated medal minted by Saddam Hussein, depicting his own face alongside Nebuchadnezzar’s.

Saddam positioned himself at the helm of the Arab world, and as the global leader against Israel, frequently threatening it with destruction. He financed countless terror attacks and suicide bombings. During the First Gulf War, he said he would destroy “half of Israel with chemical weapons”, and launched dozens of Scud missiles at Tel-Aviv. (My family experienced this first-hand, as we lived there at the time and had to take refuge in bomb shelters and wear gas masks—my mother often recalls how she couldn’t wear her gas mask because I was still a child and it frightened me when she put it on!)

Ultimately, Saddam was destroyed and met a bitter end, his “empire” crumbling into oblivion. (Fittingly, he was executed on the eve of the Tenth of Tevet, the fast day in which we commemorate the start of the Babylonian siege upon Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar!) The attempt to restore Babylon was crushed. Modern Israel’s greatest individual enemy, the financier of endless terror and violence, was eliminated. Perhaps this was a fulfilment of the Zohar’s prophecy, and another sign confirming that we are undoubtedly in the End of Days.

Patriot missiles flying over the Tel Aviv sky to intercept Iraqi Scuds during the First Gulf War in early 1991.

*When Israel was first re-established at the start of the Second Temple era, the majority of Babylon’s Jews refused to go back to the Holy Land, and chose to stay in the comforts of their new country. Most of them were lost to assimilation. Ezra, Nehemiah, and the other leaders of the time led relatively small groups back to rebuild Israel. Perhaps the mass exodus of Jews out of Iraq following the re-establishment of modern Israel was something of a tikkun for those ancient Babylonian Jews who did not make the effort to reclaim their land or participate in its rebuilding.

Pingback: The Truth About Jewish-Muslim History | Mayim Achronim