The first chapter of the Torah famously describes God’s creation of the universe. Although the text is quite brief, our Sages had much to say about the events of Creation. This is an especially important topic in Kabbalah, traditionally divided into two main headings: Ma’ase Beresheet, “the Work (or Narrative) of Creation”, and Ma’ase Merkavah, “the Work (or Narrative) of the Chariot”. The former explores the genesis and nature of the universe, along with a host of metaphysical concepts, while the latter is primarily focused on various aspects of God, and the mechanism of prophecy.

One of the most ancient Kabbalistic texts is Sefer Yetzirah, the “Book of Formation”. This book outlines in more detail how God created the universe. Since the Torah tells us that God created the world by speaking it into existence (“God said, ‘Let there be light…’”), it is taught that the building blocks of the universe are the very letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Everything that exists was fashioned out of unique combinations of these special letters.

Along with the 22 letters were the Ten Sefirot, divine energies that imbue everything within Creation. These Sefirot are sometimes said to parallel the 10 base numerical digits, from 0 to 9 (the word sefirah also means “counting”). Just as modern physicists might argue that the entire universe can be reduced to mathematical equations, Sefer Yetzirah reduces all of Creation down to these foundational numbers and letters. And so, Sefer Yetzirah begins by stating that God created the universe through lamed-beit netivot, thirty-two paths.

The Power of Sefer Yetzirah

Sefer Yetzirah is first explicitly mentioned over 1500 years ago in the Talmud (Sanhedrin 65b), where Rabbi Chanina and Rabbi Oshaia studied it together on Friday afternoons. Using the secrets described in the text, the two rabbis apparently learned how to create ex nihilo, like God. Each Friday, they would team up to create a calf out of thin air—and eat it!

It is said that the patriarch Abraham was capable of the same feat. In the well-known narrative of the three angels visiting Abraham, we read how Abraham “took butter and milk, and the calf which he had made, and set it before them…” (Genesis 18:8). Many have asked: how is it possible that the forefather of the Jewish people gave his guests a mixture of dairy and meat products? The simplest answer is that, of course, Abraham preceded the giving of the Torah and at that time there was still no prohibition on consuming dairy and meat together. However, Jewish tradition maintains that although the forefathers lived before the giving of the Torah, they still fulfilled its precepts through an oral tradition, and from the prophecies they received directly from God. So, how did Abraham put both dairy and meat before his guests?

The Malbim (Rabbi Meir Leibush ben Yechiel Michel Wisser, 1809-1879) comments on the verse by citing earlier mystical teachings that say Abraham knew the secrets of Sefer Yetzirah and fashioned the calf from scratch! This is why the verse clearly says “…and the calf which he had made [asher asah]”. Since Abraham made the calf, it was only a hunk of flesh with no divine soul (which only God can infuse), and was therefore pareve, neither dairy nor meat. In fact, many believe that Abraham was actually the author of Sefer Yetzirah. Others maintain that it was written by Rabbi Akiva, based on teachings that were initially revealed by Abraham.

A Brief Overview of the 32 Paths

Where exactly are the 32 Paths of Creation derived from? A careful analysis of the Genesis text shows that God (Elohim) is mentioned 32 times in the account of creation. Each of these 32 parallels the 32 paths. There are ten cases where the Torah says vayomer Elohim, “And God said…” in the first chapter. These 10 correspond to the Ten Sefirot. The remaining 22 mentions of God correspond to the 22 letters in the following way:

Sefer Yetzirah breaks down the Hebrew alphabet into three groups: the “mothers” (ima’ot), the “doubles” (kefulot), and the “elementals” (peshutot). There are three mother letters: Aleph (א), Mem (מ), and Shin (ש). These are the “mothers” because each is associated with one of the three primordial elements of Creation: Aleph is the root of air (avir, אויר), Mem is the root of water (mayim, מים), and Shin is the root of fire (esh, אש). These three correspond to the three times that the Torah says “God made” (Genesis 1:7, 16, and 25).

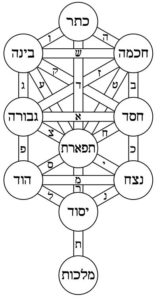

The “Tree of Life” depicting the Ten Sefirot, intertwined by the 22 Letters of the Hebrew Alphabet. Together, they make up the 32 Paths of Wisdom.

There are then 7 “doubled” letters, those that have two sounds in Hebrew: Beit (ב), Gimel (ג), Dalet (ד), Khaf (כ), Pei (פ), Reish (ר), and Tav (ת). The double sounds of beit and veit, khaf and haf, pei and phei are well-known to us today, while the other four are a little more mysterious (see below on parashat Noach, ‘Shabbat or Shabbos: What’s the Correct Pronunciation?’) The seven kefulot correspond to the seven times that the Torah says “God saw” (Genesis 1:4, 10, 12, 18, 21, 25, 31). The remaining 12 letters, the peshutot, correspond to the remaining 12 times that God is mentioned.

To summarize, the 32 paths derive from the 32 times that God is mentioned in Genesis, and further broken down into their groupings of 10, 3, 7, and 12 based on the specific type of verb used in relation to God.

Finally, all of these are embedded in the most famous of Kabbalistic diagrams, the Etz Chaim, “Tree of Life”. The 10 circles on the diagram correspond to the Ten Sefirot. The Sefirot are interconnected by 22 lines, corresponding to the 22 letters. There are three horizontal lines, corresponding to the three mother letters; seven vertical lines, corresponding to the seven doubled letters; and twelve diagonal lines, corresponding to the twelve elemental letters. This simple diagram amazingly captures a great deal of information, and is a key tool in Kabbalah—as well as the first step towards creating your very own calf!

The above is an excerpt from Garments of Light, Volume Two. Get the book here!