Chanukah is the only major Jewish holiday that is not found in the Tanakh. This is mainly because the events of Chanukah took place in the 2nd century BCE, while according to tradition the Tanakh was already compiled and codified long before by the Great Assembly at the start of the Second Temple era. In fact, historians date the earliest Greek translations of Biblical books to the 3rd century BCE. Historical records agree with the Talmud that it was King Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-247 BCE) who first commissioned the translation of the Torah into Greek, probably for his Great Library in Alexandria. How much of Scripture was translated at that point is not clear.

Although we see that the Sages continued to debate which holy books should be included in the definitive Tanakh nearly into the Talmudic period, the Book of Maccabees was never on the table. One reason is because the Book of Maccabees is not, and does not even claim to be, a prophetic work. It is simply a historical text and, contrary to popular belief, the Tanakh is not at all a history textbook. While it does record historical events—along with laws, ethics, prophecies, and more—its purpose is far greater. The Zohar (III, 152a) goes so far as to say that a person who views the Torah as a history book which simply relates “historical narratives” and “simple tales” has no share in the World to Come! “Every word in the Written Torah is a supernal word containing lofty secrets” it says, and “the narratives of the Written Torah are only the outer garments…”

Of course, it is a fundamental principle of Judaism that the Torah is an encrypted work that contains within it allusions to everything. As such, we should be able to find encoded references to Chanukah. And we do. Where did Moses hide clues to the future events of the Hashmonean Maccabees and the Chanukah festival?

The Classic Answer, Revisited

The first and most well-known answer comes from a section of the Torah that spans the parashas of Nasso and Beha’alotcha (and makes up the synagogue Torah reading for Chanukah). We end the former by reading how each of the Twelve Tribes of Israel brought their gifts to the inauguration and dedication of the Mishkan, the proto-Temple in the Wilderness. Immediately following this, at the start of Beha’alotcha (Numbers 8:2-3), we read how God tells Moses:

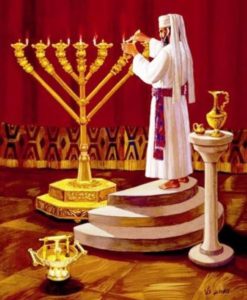

Speak unto Aaron, and say to him: “When you light the lamps, the seven lamps shall give light towards the face of the Menorah.” And Aaron did so: he lit the lamps so as to give light towards the face of the Menorah, as God commanded Moses.

The very first thing God says at the dedication of the Mishkan is for Aaron to light the Menorah. This was an allusion to a future time when Israel will once again re-dedicate God’s earthly abode (Chanukah literally means “dedication”), and discover one cruse of oil to light the Menorah. Moreover, it would be the direct descendants of Aaron—the priestly Maccabees—who would accomplish this feat.

There is something even more amazing hidden in the verses above. If reading them carefully in the original language, they make absolutely no sense (hence the poor translation). What did God mean when He instructed to light the lamps so that they “give light towards the face of the Menorah”? The lamps are the Menorah! Our ancient Sages were baffled by this verse, and some held that it meant the flames on the candles miraculously burned sideways and pointed inwards.

Alternatively, the verses can be read to mean that Aaron lit the seven lamps before him to give light forward to a future Menorah. In the merit of Aaron’s special act during the original dedication, his descendants would be able to succeed in a future rededication and Menorah-lighting. In case there was any doubt, the following verse adds that everything was done according to the “vision that God showed Moses”. What vision? It cannot simply mean that God showed Moses how to make or light the Menorah, because God obviously showed Moses how to do everything, yet this language does not appear anywhere else in the Torah with regards to any other mitzvah. Rather, what can be inferred is that God showed Moses a vision of the future, of the Chanukah Menorah being lit by the Maccabees. And so, everything came about “according to the [prophetic] vision that God showed Moses, so the Menorah was done.”

Sukkot and Chanukah

There are several more places in the Tanakh where Chanukah is alluded to. The Ba’al HaTurim (Rabbi Yaakov ben Asher, 1269-1343) notes two. First, he points out that the 23rd chapter of Leviticus, which describes all the Jewish holidays, ends with instructions for the holiday of Sukkot. Immediately after this we read (Leviticus 24:1-3):

And God spoke to Moses, saying: “Command the children of Israel, that they bring you pure olive oil pressed for the light, to light an eternal flame. Outside the veil of the testimony, in the Tent of Meeting, shall Aaron order it from evening to morning before God continually; it shall be a statute forever throughout your generations.”

The Ba’al HaTurim says this as a direct continuation of the previous chapter: the holidays don’t stop at Sukkot, but continue with the lighting of the Menorah oil! In this way, the Torah already alludes to the future holiday of Chanukah. It is worth mentioning that the Book of Maccabees states that Chanukah was instituted as an eight-day festival especially because it came right after the eight-day holiday of Sukkot (with Shemini Atzeret)—which the Jews were unable to celebrate that year because the Temple was in Greek hands. When they cleaned up the Temple, the Maccabees declared an eight-day festival to make up for the Sukkot that they had just missed.

Binah and the seven lower Sefirot (in red) correspond to the 8 days of Sukkot/Shemini Atzeret and Chanukah.

Only after this did it turn out (according to the Talmud) that the oil meant to burn for one day lasted for the entire eight-day festival that they had instituted. It was as if God placed His stamp of approval on the Maccabean festival meant to make up for Sukkot. Fittingly, the Ba’al HaTurim adds that Chanukah and Sukkot are the only two holidays where Hallel is recited each day, further solidifying their connection. (It is also worth mentioning that according to Beit Shammai, the Chanukah candles should be lit in decreasing order—eight on the first day, and one on the last day—to parallel the decreasing order of sacrifices brought on Sukkot.) Mystical texts, meanwhile, describe the eight days of Chanukah and the eight days of Sukkot (with Shemini Atzeret) in the same way (corresponding to the seven lower Sefirot, plus Binah).

All of this explains why Chanukah is eight days to begin with. After all, it didn’t have to be eight days specifically (why not seven or nine?) Some like to say that it took that many days to prepare a new batch of olive oil—but then this was winter, and no fresh olive oil could be made anyway. Others say this was the amount of time it took for a round-trip to the land of the tribe of Asher, where the best olive oil was produced (which Moses alluded to in his final blessings to the nation, Deuteronomy 33:24). The best answer is because Chanukah was originally intended to rectify a lost Sukkot.

Which brings us to the present. Today, most Jews in the world unfortunately do not celebrate Sukkot at all. In many ways, it is the most difficult of the holidays, and certainly the most forgotten. While most Jews make some effort for the High Holidays, they completely overlook Sukkot which comes just five days later. There is an idea, therefore, that Sukkot demonstrates who the real dedicated Jews are. While most go right back to their old routines right after the High Holidays, the Jews that go into the sukkah show their continued devotion to God.

But then comes Chanukah, another eight-day festival. For those Jews who don’t or can’t observe Sukkot—like the Maccabees that one year—Chanukah might be a second chance (perhaps comparable to the relationship between Pesach and the much easier Pesach Sheni). As such, it is a good sign that Chanukah is the most well-known Jewish holiday and possibly the most widely-observed. The most distant of Jews has an opportunity to commemorate Chanukah in some way—even if its just a fleeting moment looking at one of the many public chanukiot all over the world.

For the observant Jew, too, Chanukah can be a rectification. Many Jews in the North have to deal with a Sukkot that comes with copious amounts of rain, unbearably cold weather, and even snow. (Last year, my sturdy metal-and-wood-panel sukkah completely collapsed and bent out of shape after an intense windstorm. So did the massive sukkah at our synagogue.) Each day of Chanukah has a chance to spiritually make up for each lost day in the Sukkah. We certainly see this on a mystical level, where each day of Chanukah is rooted in the same Sefirah as each day of Sukkot.

Flowering Almonds

The Ba’al haTurim notes another place in the Torah that alludes to Chanukah. Following the episode of Korach’s rebellion, God instructed Moses to take a staff from each of the Twelve Tribes and engrave the name of that tribe’s leader on each staff (Numbers 17). On the staff of the tribe of Levi was engraved “Aaron”. A miracle then happened where Aaron’s staff suddenly blossomed with almond flowers. This was meant to show the nation that Aaron and his children were indeed divinely-appointed priests. God told Moses to keep that special almond staff in the Tabernacle as an eternal sign for all of Israel, to remind them not to rebel against the kohanim.

The Ba’al haTurim says this is a secret reference to the Maccabee descendants of Aaron, who miraculously saved Israel in their day. It is important to remember that the enemies at the time of the Maccabees were not just the Syrian Greeks. Worse were those Hellenized Jews who cooperated with the Greeks and sought to eliminate traditional Judaism. The Book of Maccabees recounts how one such Jew happily agreed to the Greek demand of bringing an impure sacrificial offering. Matityahu (a priestly descendant of Aaron) had no choice but to slay him to stop the desecration, thus sparking the Maccabean Revolt.

And so, the episode of Korach, and the “rebellious children” (Numbers 17:25) who supported him, is a direct spiritual precursor of Chanukah. Aaron’s miraculous almond-blossoming staff was an allusion to the miraculous victory of the Maccabees. The Ba’al haTurim adds that the gematria of almonds (שקדים) is 454, equal to “Hashmonaim” (חשמונים), the family name of the Maccabees. (The alliteration of the Hebrew word for “staff”, mat’e, and Matityahu, though spelled differently, is also interesting to note.)

Moses’ Copper Snake

Although there are at least another three places in Scripture that hint to the future Chanukah, we’ll end with just one more. The Ben Ish Chai (Rabbi Yosef Chaim of Baghdad, 1832-1909) begins his laws of Chanukah with a reminder that when lighting the candles on the first night of Chanukah, one recites three blessings: lehadlik ner, sh’asa nisim, and shehecheyanu. He says this is alluded to in Numbers 21:8, where God instructs Moses to create the nachash nechoshet, the “copper snake” staff, which was used to heal the nation from an epidemic of burning snake bites:

And God said to Moses: “Make yourself a fiery serpent [saraph], and set it upon a pole [nes]; and it shall come to pass, that every one that is bitten, when he sees it, shall live [v’chai].”

The three key parts of the verse and their three key words correspond to the three blessings of Chanukah: saraph, literally “burning”, refers to the blessing when lighting the candle; nes, “pole”, “sign”, or “miracle”, refers to the blessing of nisim, “miracles”; and v’chai, “and live” to shehecheyanu, “Who has made us live…” As in the previous two cases, there is much more here than meets the eye.

God told Moses that whoever would see the Serpent Staff would be healed. Similarly, when it comes to Chanukah it is about seeing the glow of the Chanukah candles, and making sure others see it, too. We once wrote how the Serpent Staff is a symbol of Mashiach, and elsewhere that the light of Chanukah is meant to symbolize the Hidden Light of Creation, or haganuz. We light 36 candles over the course of eight days to commemorate the Light of Creation which shone for 36 hours before being hidden.

The Midrash (Yalkut Shimoni, Isaiah 499) says the Hidden Light was locked away beneath God’s Throne, reserved for Mashiach, who will one day restore it to the world. It was that Primordial Serpent (נחש = 358) which initially caused the Light to disappear. And it is Mashiach (משיח = 358) who restores it, who overpowers the Serpent and wields that healing Serpent Staff. Back in the time of Moses, all those “bitten by a snake” were healed by staring at the Staff. Similarly, all of humanity—going back to the Garden of Eden—was “bitten by a Snake”, and seeing the spiritual glow of the Chanukah candles has the potential to heal us all.

Chag sameach!

Pingback: The Hidden History of Lag B’Omer | Mayim Achronim

Pingback: Who Was the First Rabbi in History? | Mayim Achronim