In Genesis 45 we read about Judah’s confrontation with Joseph, and the latter’s subsequent revelation of his true identity. The Torah tells us that Joseph “kissed all of his brothers and wept over them…” (Genesis 45:15) The Zohar (I, 209b) comments on this verse that Joseph wept because he foresaw the future destruction of the Holy Temples, and the exile of “his brothers, the Ten Tribes.”

The Zohar is referring to the ancient notion that ten of the Twelve Tribes of Israel were lost to history. The Zohar notes how the Torah first says that Joseph wept over Benjamin’s shoulder, and then separately states that he wept over the remaining ten brothers. This is alluding to the tragedy of the Ten Lost Tribes, among which Benjamin is not numbered. The land of Benjamin bordered Judah’s, and Jerusalem was built partly on Judah’s territory and partly on Benjamin’s. When the Northern Kingdom of Israel was destroyed, Benjamin was mostly spared, and is therefore not counted among the Lost Tribes. We see further proof of this in Megillat Esther, where Mordechai is described as being both a Judahite and a Benjaminite.

So, since Judah and Benjamin were spared, we are left with Ten Lost Tribes—supposedly. We know that the Tribe of Levi did not disappear from history either, and to this day the Levites know who they are. Are there, then, nine Lost Tribes? Or should Joseph be split in two, counting Menashe and Ephraim separately, bringing the total back to ten? On that note, Joseph weeping over his ten brothers because he foresaw their destruction is problematic, since Joseph himself is among the Lost Tribes! (Maybe he should not have wept over Judah, who survived and flourished.) The entire concept of Ten Lost Tribes is perplexing. Moreover, it has been used throughout history to support all kinds of audacious, sometimes bizarre claims. Where did it come from?

Jeroboam’s Tragic Kingdom

In I Kings 11 we read how King Solomon—as great as he was—faltered mightily towards the end of his life. In his quest for world peace, he married so many princesses (to forge political alliances) that they ended up bringing all kinds of idolatry to Jerusalem. Eventually, this caused Solomon himself to “not [be] whole with Hashem, his God, as was the heart of David his father.” (I Kings 11:4) While it is unthinkable that Solomon himself committed idolatry, it appears that he permitted his wives to build altars to their gods (11:6-10). So Hashem declared: “Because this has been in your mind, and you have not kept My covenant and My statutes, which I have commanded you, I will surely rend the kingdom from you, and will give it to your servant.” (11:11)

In I Kings 11 we read how King Solomon—as great as he was—faltered mightily towards the end of his life. In his quest for world peace, he married so many princesses (to forge political alliances) that they ended up bringing all kinds of idolatry to Jerusalem. Eventually, this caused Solomon himself to “not [be] whole with Hashem, his God, as was the heart of David his father.” (I Kings 11:4) While it is unthinkable that Solomon himself committed idolatry, it appears that he permitted his wives to build altars to their gods (11:6-10). So Hashem declared: “Because this has been in your mind, and you have not kept My covenant and My statutes, which I have commanded you, I will surely rend the kingdom from you, and will give it to your servant.” (11:11)

That servant was Yaravam ben Nevat (“Jeroboam”), the leader of the “house of Joseph”. When the prophet Ahiyah haShiloni encountered Yaravam, he took off his garment and tore it into twelve pieces before saying:

Take ten pieces, for thus said Hashem, the God of Israel: “I am about to tear the kingdom out of Solomon’s hands, and I will give you ten tribes. But one tribe shall remain his—for the sake of My servant David and for the sake of Jerusalem, the city that I have chosen out of all the tribes of Israel.” (11:31-32)

This is the earliest mention of a group of “ten tribes”. The question remains: which tribes did this refer to? We see that God left only the tribe of Judah to Solomon’s successors. This implies that God told Yaravam that he would have his own tribe, Joseph, plus the remaining ten tribes. That makes a total of eleven—all but Judah. Indeed, this is what happened after Solomon’s passing:

So Israel rebelled against the house of David, unto this day. And it came to pass, when all Israel heard that Yaravam was returned, that they sent and called him unto the congregation, and made him king over all Israel; there was none that followed the house of David, but the tribe of Judah only. (I Kings 12:19-20)

The Israelite masses initially protested the heavy taxes levied upon them. They agreed to pay those taxes in the days of Solomon, when there was a need for funds to build the Temple and the rest of Jerusalem. They argued this was no longer the case, and their tax burden should be lessened. Instead, Solomon’s successor, Rehavam, only increased the tax. The nation revolted and seceded, leaving only the tribe of Judah under the Davidic dynasty. Having said that, the following verse tells us that Rehavam “assembled all the house of Judah, and the tribe of Benjamin, a hundred and eighty thousand chosen men that were warriors, to fight against the house of Israel, to bring the kingdom back to Rehavam, the son of Solomon.” This implies that much of Benjamin remained with Judah (at the very least as mercenary warriors), being so territorially-invested in Jerusalem.

The civil war introduced above never actually happened. God made it clear that it was His will and instructed Rehavam—through his prophet Shemayah—to accept the decree. Yaravam went on to build a capital for himself in Shechem, in the land of Ephraim from which he hailed. God had given Yaravam the potential to become a truly great king of Israel. Unfortunately, Yaravam was a classic case of the age-old dictum that “Absolute power corrupts absolutely.” The Talmud (Sanhedrin 102a) records that God told Yaravam: “You and I and [David,] the son of Yishai can stroll together in the Garden of Eden.” Yaravam had the nerve to ask: “Who will walk in the lead?” to which God replied that David would. Yaravam’s unbelievable reply: lo ba’eina, “Not interested!”

Yaravam worried that he would lose his kingdom once the holidays would come around and everyone would pilgrimage to Jerusalem. The festivities would have a unifying effect on the nation and, besides, Yaravam would have to pilgrimage, too, and stand before Rehavam who would sit on his throne. To avoid this, Yaravam built two temples of his own, and instituted new pilgrimage holidays. The road to Jerusalem was blocked. In this way, he created his own cult and prevented the masses of Israel from worshipping God. For this, the Talmud concludes that Yaravam was among the few Jews who have no share at all in the World to Come. Intriguingly, the Sages state that on the very day that Yaravam began building his idolatrous temples, Remus and Romulus began building Rome (Sifre, Devarim 52).

End of the Ephraimite Kingdom

The Northern Kingdom of Israel is often referred to in the Tanakh simply as “Ephraim”. This is because Ephraim was the kingdom’s most populous tribe, the seat of its capital, and the source of many of its kings. It was also in fulfilment of Jacob’s deathbed blessing to his grandson Ephraim, who would be the most powerful of the tribes. In fact, it is said that the tense encounter between Judah and Joseph at the start of this week’s parasha was symbolic of the future standoff between the Kingdoms of Judah and Ephraim.

Despite its great power and size, Ephraim didn’t last. Steeped in idolatry, it had no divine protection. We learn from the Tanakh that there were still true God-fearing Israelites in the northern kingdom. When Judah was led by the righteous King Asa, these Israelites resettled in Judah: “out of Ephraim and Menashe, and out of Shimon; for they fell to him out of Israel in abundance, when they saw that Hashem, his God, was with him.” (II Chronicles 15:9) This is just one instance of northern tribespeople coming south to join Judah.

With regards to the tribe of Shimon, they were always the smallest and least numerous. They did not have a contiguous territory of their own, rather living in towns mostly interspersed throughout the Negev, within Judah’s territory (see Judges 19). The city of Be’er Sheva served as their capital. This was a fulfilment of prophecy and Jacob’s blessing to Shimon, which was not very positive. (Still better than Moses, who didn’t bless Shimon at all!) Due to their weakness and proximity to Judah, all of Shimon was eventually absorbed directly into Judah’s Kingdom. And so, when the Assyrians finally came and crushed the north, Shimon was spared.

We read how the Assyrians, under King Tiglath-Pileser III, first took over the Transjordan, meaning the tribal lands of Reuben, Gad, and half of Menashe (I Chronicles 5:26). They then incurred further across the Jordan and took over Naftali and the Mediterranean coast (II Kings 15:29). Finally, King Shalmaneser conquered the capital and put an end to the Kingdom of Ephraim for good, because “Hashem was exceedingly angry with Israel, and removed them out of His sight; there was none left but the tribe of Judah only.” (II Kings 17:18)

God “blotted out” the names of the other tribes and their territories. Physically, though, these people still existed for some time. As we have seen, there were many Benjaminites and Simeonites within Judah, as well as the Levite priests, of course, and those of Ephraim and Menashe that had resettled in earlier days. We further read that after the north’s destruction, the righteous King Hezekiah (who was miraculously spared from the Assyrians by God) sent letters to the survivors in the north to come to Judah. Most of them were too proud to do so, but “people from Asher and Menashe, and from Zevulun, humbled themselves and came to Jerusalem.” (II Chronicles 30:11) We see that Asherites and Zebulunites also lived in Judah. We now have clear evidence that the majority of the tribes, if not all of them, continued to exist in the Holy Land after the northern kingdom’s destruction. Ultimately, these tribes assimilated into Judah and eventually people forgot their ancient tribal affiliations. Everyone simply became a “Judahite”, Yehudi.

Of all the possible names for the nation, this one is certainly most fitting. It literally means “gratitude”, which Judaism, with all of its ceaseless prayers and blessings, is all about. Jews recite a “thank you” berakhah before and after eating any food, when purchasing new clothing, seeing exotic animals, and even going to the bathroom! Gratitude permeates every moment of a Jew’s life. More significantly, within Yehudah (יהודה) is the name of God, the Tetragrammaton. Wherever the Yehudim go, we carry God with us.

Now, what about all those that the Assyrians expelled from the Holy Land?

The Legend of the Lost Tribes

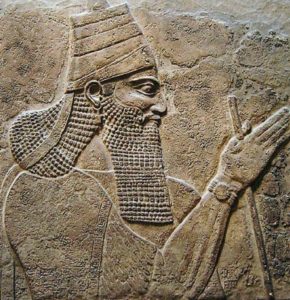

An engraving of Tiglath-Pileser III, from the walls of his palace

The Tanakh tells us that the Assyrians “carried Israel away unto Assyria, and placed them in Halah, and in Habor, on the river of Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes.” (II Kings 17:6, and I Chronicles 5:26.) These places are identified with locations not too far away from Israel. The Habor and Gozan Rivers are known to be tributaries of the Euphrates River. “Halah” is most likely the same as “Khalah” mentioned in Genesis 10:11, also in Mesopotamia. In fact, archaeologists digging in Khalah (alternately known as Nimrud), near present-day Mosul, Iraq, discovered the palace of Tiglath-Pileser III, the king who began Israel’s destruction. It is logical that Tiglath-Pileser would exile his newly-enslaved subjects to his own capital city for free labour.

Despite this, all kinds of legends arose over the centuries describing the Israelites wandering far further away. The earliest mention of this is possibly in the apocryphal “Second Book” of Ezra (or II Esdras, sometimes called IV Esdras or ‘The Apocalypse of Ezra’). It claims to be a sequel to the Biblical Book of Ezra, and allegedly contains Ezra’s visions of the End of Days. There, “Ezra” describes how Mashiach will come to Mt. Zion and bring peace to the world.

…he gathered another peaceable multitude unto him. Those are the ten tribes, which were carried away prisoners out of their own land in the time of King Hoshea, whom Shalmaneser, the king of Assyria, led away captive, and he carried them over the waters, and so came they into another land. (2 Esdras 13:39-40)

Esdras goes on to say that God did a miracle for these exiles when they reached the Euphrates by causing its waters to subside so that Israel could cross. They then journeyed for another year and a half until they reached a place called Arsareth (13:45). The book refers to the messiah as “My son”, meaning it was likely composed by the early Jewish-Christians. It was written in Greek (not Hebrew), and is dated to no earlier than around 80 CE. Others say these Christian remarks were later edits by future Christian scribes, the text not coming into its current form until the 3rd century CE. Whatever the case, Esdras was never accepted as authentic in the Jewish world. The mention of “ten tribes” in a distant land is an error, an indication of the author’s own ignorance of Tanakh, which never specifically mentions ten tribes being lost. In fact, according to the Books of Chronicles (Divrei haYamim), only the tribes of Reuben and Gad—which were settled east of the Jordan River—were permanently exiled and never returned! (See, for instance, I Chronicles 9:1-3 and II Chronicles 5:26.) People from all the other tribes had come back and continued to live in Judea and Jerusalem during the early Second Temple era.

Around the same time as Esdras, Josephus (c. 37-100 CE) wrote of the Ten Lost Tribes as well. When describing the return to Judea at the start of the Second Temple era, he says that most of the Israelites stayed in Babylon so “there are but two tribes in Asia and Europe subject to the Romans, while the ten tribes are beyond Euphrates till now, and are an immense multitude, and not to be estimated by numbers.” (Antiquities of the Jews 11.5.2:133) Josephus explains that two tribes (presumably Judah and Levi) remain in the known world, while the rest are possibly somewhere far beyond the Euphrates, and he hopes in large numbers. It is very possible that Josephus was the source for the above claim in II Esdras. Josephus was probably relaying an old legend that Israelites still exist in some distant, mythical land—despite no evidence to support the claim, and in contradiction to the Tanakh which says they weren’t exiled very far at all, and most of them had returned.

The legend that the Lost Tribes exist continued to survive until the modern era, when the whole of the world’s geography was uncovered, and no true “Lost Tribes” could be found. In reality, most of those ancient Israelites simply became Judahites, and the rest assimilated into the other nations—Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes, and Persians. The Mishnah already stated that “the Ten Tribes will not return”, though Rabbi Eliezer holds out some hope that they might (Sanhedrin 110b). Rabbi Akiva, on the other hand, staunchly opposed such notions, and the Gemara there begins by teaching that the Ten Tribes don’t even have a share in the World to Come. In other words, not only will they not return physically, they won’t even return spiritually! They are finished for good. Nonetheless, other minority opinions state that perhaps they shall return. In the past, when much of the world was undiscovered, the hope that the Ten Tribes are “lost” somewhere in the unknown remained. And that gave rise to all kinds of incredible claims, a few of which we will explore.

Brits, Danes, Natives—and Everyone Else

Many Jewish communities to this day seek to be identified with the ancient Israelites. This includes, among others, Afghani Jews (along with the non-Jewish Pashtuns of Afghanistan, which some have claimed descend from the Lost Tribes), Indian Jews, and the Bukharian Jews of my own community. There is no doubt that Jews inhabited these regions for centuries, going back at least two millennia. It is much harder, though, to prove any link to the Lost Tribes. The argument is based on the identification of those Biblical places mentioned in I Chronicles 5:26: Halah, Habor, Hara, and the River Gozan. Some identified the Gozan with the Oxus River, also known as the Amu Darya, which runs through Uzbekistan and Afghanistan.

The Oxus really was the extent of the Assyrian, Persian, and Greek Empires, so it is possible that the exiled locations are near it. Etymologically, “Hara” is thought to be the origin of Bukhara in Uzbekistan, and “Halah” of Balkh in Afghanistan. While this is compelling, it isn’t nearly enough to draw conclusions. We know that there was a great deal of Jewish migration throughout the centuries, especially in places like Bukhara and Balkh which are centrally-located on the Silk Road. These places were not isolated from the rest of the Jewish world, and Jews living there were not “lost” in any way.

(In later legends, the Gozan River became the Sambation River. This impenetrable river flows with rocks, or flows so strongly it is impossible to cross. In some places, the Sambation is described as being crossable only on Shabbat, when it is forbidden to cross! [“Sambation” is probably a corruption of Sabbaticon, the “Sabbath River”.] It is therefore said that the Lost Tribes are hidden [or, more accurately, trapped] there—perhaps until the End of Days.)

On the other side of the map, some of the Beta Israel of Ethiopia have claimed descent from the “Lost Tribes”. There are rabbinic sources that link them to the tribe of Dan. However, there is no indication anywhere that the Lost Tribes were exiled to Africa. Genetic studies have shown no link between modern Ethiopian Jews and ancient Israelites, though their DNA certainly contains Jewish elements from Jews that settled in Africa in the 4th and 5th centuries CE.

Somewhat ironically, a number of white Europeans have claimed descent from the tribe of Dan, too. There are those who say this is why “Dan” mysteriously appears in so many European locations such as the Danube River (as well as the Dnieper and Dniester), Dunkirk, and even Sweden and Denmark (which they call Danemark). As far back as the 15th century, there were Scandinavians that believed they were the descendants of the Israelite Danites (this is referred to as “Nordic Israelism”). Some Irish scholars have claimed the Celts originated from sea-faring Danites that settled Ireland, which explains why the Celts claimed descent from Tuatha Dé Danann. As explored in the past (see ‘When Jews and Greeks Were Brothers: The Untold Story of Chanukah’ in Garments of Light, Volume Two), there are those who made the case that even the Greeks came from the Israelites, since one of their legendary founders is called Danaus.

Meanwhile, some Brits claimed that they were descended from the Lost Tribes, too (this is referred to as “British Israelism”). They argued that the “Saxons” were so named because they were “Isaac’s sons” (!) and London also has a Danite origin. I’ve even heard the suggestion that “Britain” comes from the Hebrew brit, “covenant”. (Unfortunately, they missed the part where Britain would actually mean “no covenant”.) British Israelism began in the 17th century, and played a role in the British allowing Jews to return to England (having been expelled in 1290 CE). It gained even more popularity in the 19th century, and some adherents supported Zionism. Still, this does not mean that they especially liked Jews; in fact, it was often used as an antisemitic canard, that Jews are not true Israelites, but British Christians are!

On that note, one of the key players in getting Jews back to England was Rabbi Menashe ben Israel (Manoel Dias Soeiro, 1604-1657). Although he was a respected rabbi in Holland, and head of its first Hebrew printing press, he found it hard to make a living. Two wealthy Jews offered Rabbi Menashe to move to the Dutch colony of Recife in Brazil to head a new yeshiva, so he did. While there, he became convinced that the Native Americans were descendants of the Lost Tribes! After returning to Holland, he published The Hope of Israel to explain. The notion that the Native Americans were the lost Israelites later inspired the Mormons, who built their entire religion around this claim.

(A fascinating aside: Rabbi Menashe was one of two rabbis in Dutch Brazil, along with Rabbi Isaac Aboab da Fonseca. Both of them had to flee when the Dutch lost their colony to the Inquisitionist Portuguese. Over the course of the nine-year war, most of the Jewish refugees returned to Holland. However, one of the ships took a detour and ended up founding the first Jewish community in North America, in New Amsterdam, later renamed New York City!)

To conclude, the tribes of Israel were never really lost, but simply amalgamated into Yehuda. There are no “Ten Lost Tribes”, and never were, aside from the countless Jews lost to history through assimilation (whether by force, by choice, or by time). All Jews probably carry some minute genetic elements from a mix of all the ancient Israelites. With this in mind, perhaps we need to rethink how we understand the Haftarah for this week’s parasha, where God tells the prophet Ezekiel:

Behold I will take the stick of Joseph, which is in the hand of Ephraim and the tribes of Israel his companions, and I will place them with him, with the stick of Judah, and I will make them into one stick, and they shall become one in My hand… And I will make them into one nation in the land upon the mountains of Israel, and one king shall be to them all as a king; and they shall no longer be two nations, neither shall they be divided into two kingdoms anymore.

Instead of seeing this as a prophecy exclusively for the End of Days, maybe we should read it as a prophecy already fulfilled in the Second Temple era. Already back then, all of Israel were unified into a single nation, and were no longer “divided into two kingdoms”. In the Second Temple era, Israel had enjoyed a period as a unified, independent state. Now, again, we live this reality, and all that is left to be fulfilled is the remainder of the passage:

And they shall dwell on the land that I have given to My servant, to Jacob, wherein your forefathers lived; and they shall dwell upon it, they and their children and their children’s children, forever; and My servant David shall be their prince forever. And I will form a covenant of peace for them, an everlasting covenant shall be with them; and I will establish them and I will multiply them, and I will place My Sanctuary in their midst forever…

Pingback: The Economics of Jewish History | Mayim Achronim

Pingback: The Last Oppression | Mayim Achronim

Pingback: The Truth About the Lost Tribes of Israel | Mayim Achronim