This week’s parasha is Shemini, “eighth”, referring to the eighth day of the Mishkan’s inauguration ceremony. On this day, the sons of Aaron, Nadav and Avihu, brought an unsanctioned incense offering, and perished because of it. The Torah goes on to describe various sacrificial and priestly laws before going into the rules for kosher food.

When it comes to land animals, those that have split hooves and chew cud are kosher. Animals that do not have both signs are not kosher. The Torah then goes on to give four examples of animals that have one of the signs, but not the other: the camel chews cud, but does not have a completely split hoof; the pig has a split hoof, but does not chew cud; and the shafan and arnevet (unknown species often described as rabbits, hyraxes, or badgers), who chew cud but do not have split hooves.

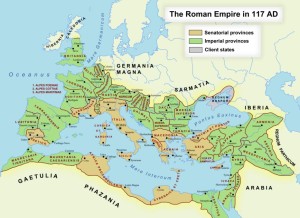

The Torah uses these as examples of non-kosher animals that were present in Israel and surrounding regions in those days; animals that were familiar to the Israelites. The Torah does not state anywhere that these must be the only four non-kosher animals in the entire world that possess one sign, and not the other. Yet, somehow it became popular for Torah lecturers, particularly in the world of kiruv (Jewish outreach), to suggest that thousands of years ago, the Torah predicted there are only four such animals in the whole world, and to this day, no other animals have been found that only offer one sign. While ancient Jewish literature has plenty of amazing foresight into scientific matters – which may be used to show people its deep wisdom and divinity – this particular argument is highly flawed. The truth is, there are other animals that have one of the two signs, and not the other. Let’s take a look at a few examples.

Hippos & Llamas

A famous problem was the case of the hippopotamus. A hippo has the same foot structure as a pig, and like a pig, does not chew its cud. (While it is herbivorous, eating mostly grass and aquatic plants, hippos have been noted to even eat meat on occasion.) A hippopotamus is thus a perfect example of another animal that has split hooves but does not strictly chew cud.

Hippo and Pig Hooves

Despite this, people will still go out of their way to insist that the Torah’s four animals must be the only four. Some even suggest that the hippopotamus must really just be another type of pig! Of course, hippos are no more pigs than they are cows, or any other animal. In fact, today scientists know that hippos are most closely related to whales (and DNA analysis confirms this).

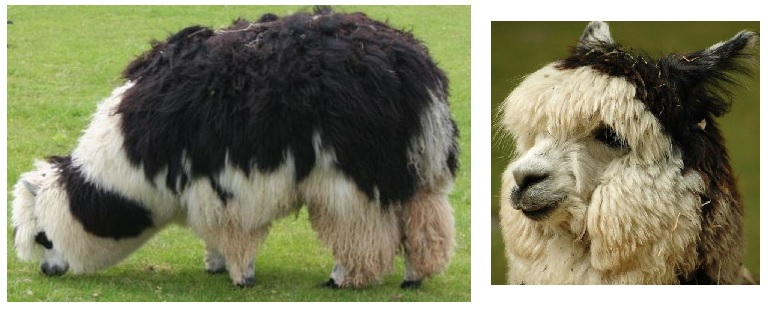

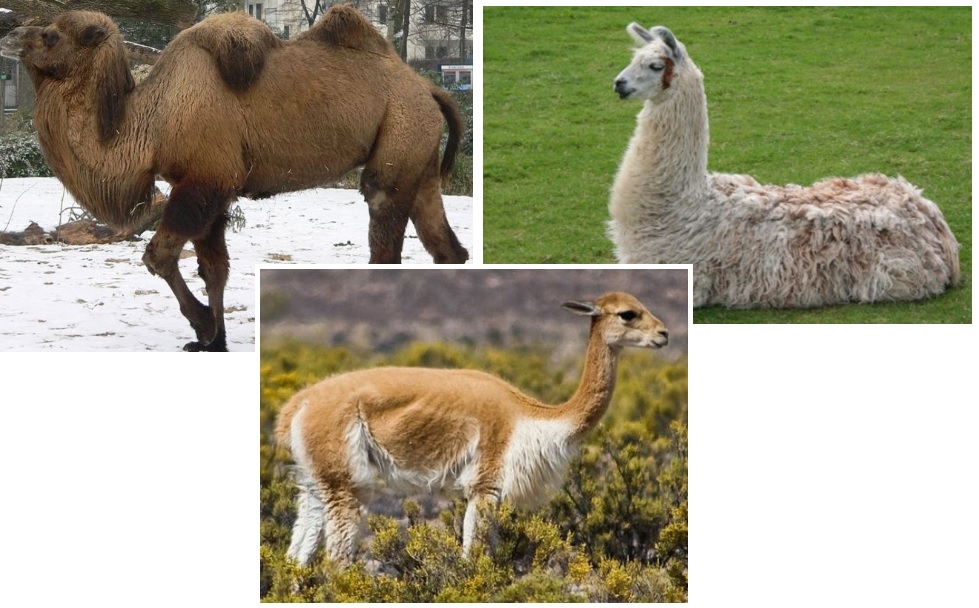

On the other side of the spectrum are the animals that chew cud but do not have fully-split hooves. The llama and alpaca are good examples. Once again, there are those that will insist these must be just another type of camel – even though they have wool, and no humps, are commonly used for their meat, and were once thought to be closer to sheep.

Huacaya Alpaca

Some might argue that since camels and llamas are officially grouped by scientists in the same family of ‘camelids’, they can be thought of as being basically the same. In reality, a zoological ‘family’ could be a vast group with very different species. For example, donkeys and horses are in the same family, yet no one in Biblical times (or today) would consider them “the same”. In fact, a donkey has a totally different status in Judaism than a horse, and a firstborn donkey is required to be redeemed in Jewish law. No rabbi would permit a horse to be redeemed in place of a donkey!

Camelids: Bactrian Camel, Llama, and the deer-looking Vicuna

Truth in Kiruv

At the end of the day, the debate over the four animals listed in the Torah matters very little. The Torah does not claim these are the only four animals, so there is no need to make that conclusion. The problem is when people do make that conclusion, then use it as a proof to convince others of the divinity of Judaism. Those victims might be convinced initially, then go on to do their own research and discover that the “proof” was actually false, which may then serve to push them away from Judaism altogether.

Besides, there are many more solid arguments from ancient Jewish literature that can be used instead. Here are a couple of much better ones:

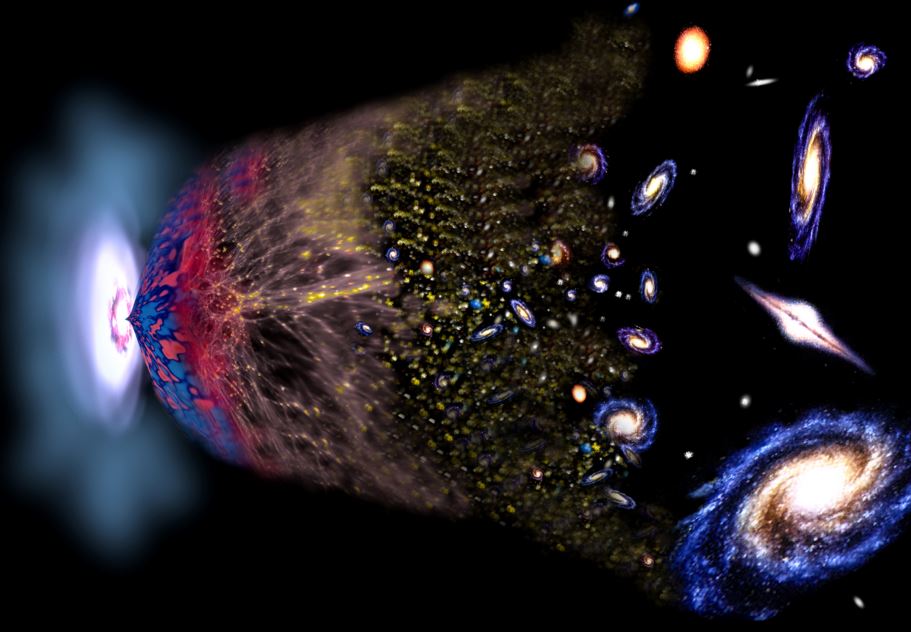

בְּשַׁעְתָּא דִּסְתִימָא דְכָל סְתִימִין בָּעָא לְאִתְגַּלְּיָא, עֲבַד בְּרֵישָׁא נְקוּדָה חֲדָא, וְדָא סָלֵיק לְמֶהֱוֵי מַחֲשָׁבָה. צַיֵּיר בָּהּ כָּל צִיּוּרִין חָקַק בָּהּ כָּל גְּלִיפִין… וְרָזָא דָא, בְּרֵאשִׁית בָּרָא אֱלֹהִים. זֹהַר, דְּמִנֵּיהּ כָּלְהוֹ מַאֲמָרוֹת אִתְבְּרִיאוּ בְּרָזָא דְאִתְפַּשְׁטוּתָא דִנְקוּדָה דְּזֹהַר סְתִים דָּא

זוהר חלק א (בראשית) דף ב/א, טו/א

“When God began to create, He first made a singular point, with which he then formed all formations, and carved out all things… And the secret of ‘In the beginning, God created…’ [Genesis 1:1] is radiance [zohar], from which all Utterances were created, in the secret of the expansion of the point of radiance.”

The Zohar, a mystical commentary on the Torah first published in the 13th century (based on much older teachings) describes that creation began from a singular point of radiation that expanded to give rise to all things. This is precisely what science tells us today with the Singularity that spawned the Big Bang, and the cosmic expansion and cooling that followed, giving rise to all matter. (See ‘Torah on the Big Bang and the Age of the Universe’ here for more.)

The Zohar also tells us:

דהא כל ישובא מתגלגלא בעגולא ככדור, אלין לתתא, ואלין לעילא, וכל אינון בריין משניין בחזוויהו משנויא דאוירא, כפום כל אתר ואתר

זוהר חלק ג (ויקרא) דף י/א

“… The entire planet is rotating in a circle like a ball. There are people below, and people above, all different in appearance due to the different atmospheres of each land.”

At least seven centuries ago, the Zohar already taught that the Earth is spherical, and more significantly, that it is rotating (which scientists only confirmed in the 19th century – see Foucault’s 1852 pendulum experiment). The Zohar also states that despite the Earth’s spherical nature, people live above and below, without falling off the planet, and that people living in different lands have different features because of different environmental conditions, hinting at biological adaptation.

Credit: Dailygalaxy.com