This week’s Torah reading is named after Moses’ cousin, Korach, and describes his rebellion against the leader of the Jewish people. Rashi’s commentary quotes a number of Midrashic texts to explain Korach’s motivation. Korach was a very wealthy and very wise man. Yet, despite being a distinguished member of the community, and Moses’ cousin, he was not appointed to any prominent roles. The high priesthood was bestowed upon Aaron, while the leadership of the Kohatithes (one of the major divisions of the Levites) was given to Elitzaphan, who was younger than Korach.

Upset by these developments, Korach gathered 250 others and protested: “…the entire congregation, all of them, are holy, and God is in their midst, so why do you raise yourselves above God’s assembly?” (Numbers 16:3) Korach essentially accused Moses of nepotism: putting his own favourites in holy positions to rule over the people, when in reality all the people should be on a high and exalted level, as they are all equally part of God’s assembly.

This was a very good argument, and many were swayed by Korach. After all, God had said to the people that “… you will be a kingdom of priests, and a holy nation” (Exodus 19:6). Amazingly, Rashi writes that Moses himself agreed with Korach! Moses said:

“Among the nations, there are many forms of worship and many priests, and they do not all gather in one temple. We, however, have only one God, one ark, one Torah, one altar, and one High Priest, but you two hundred and fifty men are all seeking the High Priesthood! I, too, would prefer that. Here, take for yourselves the service most dear [to God] of all: it is the incense, more cherished than any other sacrifice, but it contains deadly poison, by which Nadav and Avihu were burnt, so be warned…” (Rashi on 16:6)

The Incense Offering

The ketoret, or incense offering, was the greatest of Temple services, and could only be performed by the High Priest. It is said that anyone else who attempted it (including the High Priest if he was not in the highest state of purity) would die immediately. The Torah already relayed the story of Nadav and Avihu, the sons of Aaron who tried to bring their own incense, and perished.

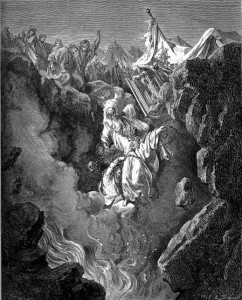

“Death of Korah, Dathan, and Abiram” by Gustave Doré

So, Moses told Korach and his supporters that he would have loved for everyone to be at the level of high priesthood. This is how God had originally intended it after all, and one day in the future it would be so. At the present moment, though, the people were simply not ready for it. If they indeed thought they were all capable of being the High Priest, Moses suggested for them to each bring their own incense. He warned them, though, not to forget what had happened to Nadav and Avihu.

The narrative continues with Korach and his supporters bringing their own incense offering, with the result being utter failure, and every one of them losing their life for it (16:35). Korach himself, together with his main supporters Datan and Aviram, was given a more severe punishment: they were swallowed up by the earth. Interestingly, this specific punishment was decreed by Moses. Why did Moses specifically want Korach to be swallowed up by the earth?

Cain and Abel

The Arizal explains that Moses and Korach were reincarnations of Abel and Cain (Sha’ar HaGilgulim, Ch. 29 and 32). Cain had risen up against Abel, argued with him, and then murdered him. The text states that the earth had “opened its mouth” to receive Abel’s blood (Genesis 4:11). This time around, Cain’s soul (within Korach) again rose up against Abel’s soul (within Moses) and quarreled with him. Now, to complete the spiritual rectification, measure for measure, it was Abel that buried Cain in the earth, with the text once again saying that the earth had “opened its mouth” (16:32).

Water and Ice

Practically speaking, Moses and Korach represent two types of people, indicated by their names. Moses, Moshe, was a name given by the Pharaoh’s daughter, who said ki min hamayim meshitihu, “For I drew him out of the water.” Korach, on the other hand, has the exact same Hebrew spelling as kerach, ice. Moses represents water; Korach represents ice. The latter is cold, hard, and unyielding, expanding ever larger as it freezes, symbolic of an inflating ego. The former is fluid, life-giving, and always flows to the lowest possible point, symbolic of humility. The lesson here is for each person to emulate the watery traits of Moses, and not the frozen qualities of Korach.