This Sunday evening brings Tu b’Shevat, the “New Year for Trees” and the start of a new agricultural and fruit-tithing season. Fruits play a huge role in Judaism, starting right at the beginning of the Torah with a special double-blessing on Day Three of Creation when fruit-bearing trees emerged. Then comes the Forbidden Fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, setting in motion all of history as we know it. The importance of fruits carries over into the Talmud, where the Sages teach that a Torah scholar should not live in a place that does not have a wide variety of fruits! The passage (Sanhedrin 17b) begins like this:

וְתַנְיָא: כׇּל עִיר שֶׁאֵין בָּהּ עֲשָׂרָה דְּבָרִים הַלָּלוּ אֵין תַּלְמִיד חָכָם רַשַּׁאי לָדוּר בְּתוֹכָהּ: בֵּית דִּין מַכִּין וְעוֹנְשִׁין, וְקוּפָּה שֶׁל צְדָקָה נִגְבֵּית בִּשְׁנַיִם וּמִתְחַלֶּקֶת בִּשְׁלֹשָׁה, וּבֵית הַכְּנֶסֶת, וּבֵית הַמֶּרְחָץ, וּבֵית הַכִּסֵּא, רוֹפֵא, וְאוּמָּן, וְלַבְלָר, וְטַבָּח, וּמְלַמֵּד תִּינוֹקוֹת. מִשּׁוּם רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא אָמְרוּ: אַף מִינֵי פֵירָא, מִפְּנֵי שֶׁמִּינֵי פֵירָא מְאִירִין אֶת הָעֵינַיִם

And it is taught: A Torah scholar is not permitted to reside in any city that does not have these ten things: A court that has the authority to flog and punish transgressors; and a charity fund for which monies are collected by two people and distributed by three. And a synagogue; and a bathhouse; and a public restroom; a doctor; and a craftsman; and a scribe; and a ritual slaughterer; and a teacher of young children. They said in the name of Rabbi Akiva: The city must also have varieties of fruit, because fruits illuminate the eyes.

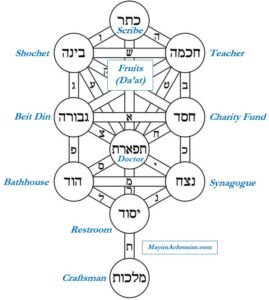

It’s easy to see how the ten requirements neatly parallel the Ten Sefirot: a charity fund is Chessed, while a beit din is Gevurah (or Din). A doctor (rof’e) is tied directly to Tiferet, the root of balance and healing. A beit knesset is a place to connect and communicate with the Eternal One, Netzach. The bathhouse is tied to the Sefirah of Hod (as explained in detail in the recent class on health). Today’s equivalent of the Roman bathhouses they used to have in Talmudic times is probably something like a country club or fitness room (with amenities like pool, sauna, and hot tub). A restroom corresponds to Yesod for obvious reasons. Thankfully, we live in an age where there are restrooms everywhere, including in our own homes. A craftsman who can construct things ties to the “kingdom” of Malkhut. (In fact, numerically, the value of “craftsmanship”, אמנות, is 497, one more than Malkhut, מלכות, which is 496.) Rashi says that “craftsman” here is referring to a bloodletter (also discussed in the same class on health linked to above). Kabbalistically, blood parallels the lowest level of soul, the nefesh, which parallels Malkhut.

The remaining three correspond to the upper three Sefirot, the Mochin. The shochet to Binah (since he must be both God-fearing and Torah-learned, but also knowledgeable in the biology and physiology of the animals), the teacher to Chokhmah (as his job is to spread wisdom and educate others), and the scribe to Keter (for reproducing the Word and Will of God). Then Rabbi Akiva adds an eleventh requirement, which is appropriate since there is a hidden “eleventh” Sefirah, too, the opposite face of Keter, called Da’at. The requirement corresponding to Da’at is having fruits, fittingly reminding us of the Etz haDa’at, the Forbidden Fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. The big question is: why are fruits so important that they are a fundamental requirement for a Torah scholar?

The remaining three correspond to the upper three Sefirot, the Mochin. The shochet to Binah (since he must be both God-fearing and Torah-learned, but also knowledgeable in the biology and physiology of the animals), the teacher to Chokhmah (as his job is to spread wisdom and educate others), and the scribe to Keter (for reproducing the Word and Will of God). Then Rabbi Akiva adds an eleventh requirement, which is appropriate since there is a hidden “eleventh” Sefirah, too, the opposite face of Keter, called Da’at. The requirement corresponding to Da’at is having fruits, fittingly reminding us of the Etz haDa’at, the Forbidden Fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. The big question is: why are fruits so important that they are a fundamental requirement for a Torah scholar?

The simple answer that Rabbi Akiva gives is that fruits are good for the eyes. Indeed, fruits are very nutritious and have things like vitamin A (retinol) which is helpful for vision, as well as different pigments that help with eye health. Today we know that carotenoids (which give fruits and vegetables their yellow and orange colours) protect the eye’s retina, while anthocyanins (which make fruits and flowers blue or purple) have been shown to boost rhodopsin proteins which allow one to see. Evidence suggests that both lycopene (the red pigment) and vitamin C reduce cataracts, the leading cause of blindness. So, modern science confirms Rabbi Akiva’s teaching. And it’s all the more important for Torah scholars to have good vision since they spend so many hours a day pouring over books and fine print.

Fruits are also important for Jewish practice, and are intricately tied to the Jewish calendar. We need various fruit and tree varieties for Rosh Hashanah simanim, and for the four species of Sukkot; to fulfil mitzvot like orlah and bikkurim, to recite a bor’e pri ha’etz blessing, to make charoset for Pesach, and to conduct a proper Tu b’Shvat seder. So, of course, having access to fruit is absolutely vital for a Torah scholar. That said, how can we understand Rabbi Akiva’s teaching on a deeper level?

Rabbi Akiva says that fruits are meirin et ha’eynaim, “illuminate the eyes”. This is a clear allusion to the Garden of Eden, where the Serpent told Eve that if she eats of the Fruit, “your eyes will be open and you will become like Elohim” (Genesis 3:5). The next verse says that Eve now saw that the Fruit was good to eat and “desirable for the eyes”. And the following verse says that once Adam and Eve consumed the Fruit, “the eyes of both of them were opened”. There is a constant repetition of “opening eyes” in relation to the Fruit, taking us right back to Rabbi Akiva’s teaching of fruits being good for opening one’s eyes. Because, ultimately, what is the purpose of the Torah scholar? The goal is cosmic tikkun, rectification, restoring the world to its primordial holy state, as it was in the Garden of Eden. That means reversing the “primordial sin” of the Forbidden Fruit—and the curses that came about as a result—and recreating a reality where Hashem is openly revealed.

So a Torah scholar needs ten things to facilitate this work and to accomplish that ultimate goal. What follows is “illuminating” one’s eyes as it was originally for Adam and Eve, where they could see Hashem openly revealed and communicate with Him directly. Recall that Rabbi Akiva’s primary disciple, Rabbi Meir, taught that Adam and Eve were originally clothed with “garments of light” (כׇּתְנוֹת אוֹר), and only after did that get replaced with “garments of skin” (כׇּתְנוֹת עוֹר), or “garments of leather” (3:21). Rabbi Akiva specifically uses the expression meirin et ha’eynaim, reminding us of Rabbi Meir’s teaching about being able to see the divine light openly revealed. This is the world we are working towards—and something deeper to meditate on as we consume our illuminating Tu b’Shevat fruits.

Chag Sameach!