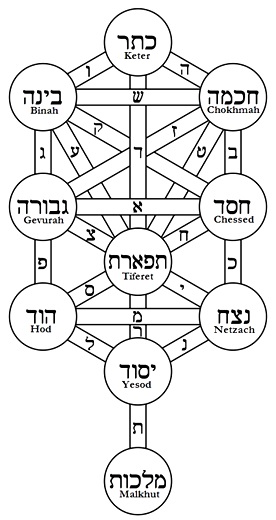

Between the holidays of Pesach and Shavuot it is customary to read one chapter of Pirkei Avot on each of the six Sabbaths. While the plain text of the Mishnaic tractate Avot is already full of significant statements that can be meditated on at length, a closer look reveals much more beneath the surface. One thing that becomes clear is that each chapter has its own unique structure and essence. When it comes to Chapter One, we find an obvious pattern—a hidden geometry based on a fundamental Kabbalistic principle. As is well-known, the central concept of Jewish mysticism is the framework of the Ten Sefirot. These are arranged in three columns, and in three rows:

The most important of the three rows is the middle one; composed of Chessed on the right, Gevurah on the left, and Tiferet in the centre. In fact, mystical texts often see the entire right column as an extension of Chessed, and the entire left column as Gevurah, and the entire middle column as Tiferet. The dichotomy between Chessed and Gevurah permeates Jewish writings, both mystical and plain. For example, in Jewish law one must put on their right shoe first and their right sleeve first, and just about everything is done with the right side first—to favour the side of Chessed, kindness. This is also why the right tefillin strap is longer than the left, and why we wash the right hand first in netilat yadayim. We favour the right because the left is Gevurah, “restraint” or “severity”, also known as Din, “judgement”. The left is a more “negative” quality, and is also associated with the impure forces of the Sitra Achra, along with the evil inclination. We favour the right in order to overpower the left.

Balancing these two is Tiferet in the middle, also referred to as Rachamim, “mercy” or “compassion”, as well as Emet, “truth”. Too much Chessed is not good, just as too little Gevurah is not good. A person should judge themselves regularly in order to iron out their own weaknesses and improve. And a person should not be too kind and easy-going, for then they might become a pushover and get taken advantage of. The true path is Tiferet, where severity is mitigated by kindness—hence the term Rachamim, or mercy (for more, see ‘The Meaning of Tiferet’). This is actually where many practices in Judaism come from.

For example, it is customary to add a few drops of water to the Kiddush cup of wine. This is because the red, bitter wine represents Gevurah, while the clear, life-giving water represents Chessed. Adding water serves to “sweeten the judgement”, and brings balance to the opposing forces. For the same reason, Israel has three patriarchs: first came the overly hospitable and generous Abraham, who was Chessed; then came the tough, reclusive Isaac (whose relationship with God is described as pachad, “fear”), who was Gevurah; only then came the wholesome Jacob to balance the previous two. Due to his measured approach, it was Jacob who merited becoming “Israel” and fathering the nation. Abraham leaned just a bit too far to the right, while Isaac was just a bit too far on the left. In Jacob, God had the perfect balance. Fittingly, our tractate is called Avot, literally “patriarchs”, so there is an obvious allusion to our three patriarchs here. Indeed, we find that the first chapter is built all around such threes.

Truth in Threes

The Kabbalistic trifecta described above is not just a mystical idea, but is seen as the foundation for all of Creation. It represents the cosmic balance of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Three is a most special number, and the Talmud (Shabbat 88a) points out that God “gave a three-fold Torah to a three-fold people through a third-born, on the third day, in the third month.” There are three parts to the Holy Scriptures (Torah, Nevi’im, Ketuvim), and three parts to the Jewish people (Kohen, Levi, Israel), and Moses was a third-born child (after Miriam and Aaron), and the Torah was given on Sinai after three days of purification, in the third month of Sivan. All of these threes reflect the mystical trio of Chessed, Gevurah, and Tiferet.

Similarly, we see that many statements in Pirkei Avot are relayed in three clauses. In fact, every single verse in the first chapter of Pirkei Avot is split into three. When further examining each verse, we see how the Sages clearly paralleled each of their three clauses to one of the three Sefirot. The first teaching comes from the men of the Great Assembly who taught: “Be cautious in judgement, raise many disciples, and make a fence around the Torah.” The first explicitly speaks of din, “judgement”, referring to the Sefirah of Gevurah. The second is about having many students, just as Chessed represents abundance (while Gevurah is restraint), and just as Abraham was famous for having many students (while Isaac, our Sages say, only had one). The last clause is about the Torah, and the Kabbalists always speak of the Torah as emanating from the central Sefirah of Tiferet, or Emet.

In the next verse, Shimon haTzadik teaches that “the world stands on three things: on the Torah, on the service of God, and on acts of kindness.” Once more, the parallel to the three Sefirot is clear: kindness is Chessed, service (avodah, literally “labour”) is Gevurah, and the Torah is Tiferet. Shimon’s student Antigonus taught: “Do not be as servants who serve their master for the sake of a reward; rather, be as servants who serve their master not for the sake of a reward; and may the awe of Heaven always be upon you.” The one who serves his master (or Master) only out of obligation and fear is in the difficult realm of Gevurah, while the one who serves his master out of love is, of course, in Chessed. Whatever the case, one should never forget the truth of who the real Master is, and have the awe of Heaven upon them (Tiferet).

Then comes Yose ben Yoezer: “Let your home be a meeting place for the wise; dust yourself in the soil of their feet, and drink thirstily of their words.” The wise, like the Torah, stem from the Sefirah of Tiferet. One should roll around in the dust of their feet (meaning to humble one’s self before them, which is Gevurah) and drink thirstily (evoking water and abundance, both symbolic of Chessed).

His partner, Yose ben Yochanan, taught: “Let your home be wide open, and let the poor be members of your household, and do not engage in excessive conversation with the woman…” To have one’s door open is to be hospitable—Chessed. To remember the poor, who are undoubtedly experiencing tremendous din upon them, is Gevurah. We have already discussed in the past the real meaning of not speaking excessively to “the” woman. Rabbi Yose explains that this will ultimately lead a man to “neglect the study of Torah”—Tiferet.

Yehoshua ben Perachiah then famously says: “Assume for yourself a master, acquire for yourself a friend, and judge every man to the side of merit.” One’s master will (hopefully) lead them to the balanced life and teach them truth—Tiferet; a friend is a companion in Chessed; judging others favourably is the right way to approach Din and Gevurah.

Nitai haArbeli speaks next: “Distance yourself from a bad neighbor, do not cleave to a wicked person, and do not abandon belief in retribution.” While one should always be kind to their neighbours, they should also be weary of the bad apples. Remember, too much Chessed is not a good thing! One should certainly distance from the wicked person (who is attached to that negative Left Side). And no matter how hopeless it may seem (especially now with what’s going on in the world), there will in fact be a great reckoning to come, just as the Torah promises—do not lose hope in this truth! The “era of Tiferet” will soon be upon us, so don’t abandon belief in divine retribution.

Yehuda ben Tabbai then says that one should not act like a lawyer (Chessed), and one should be neutral when judging (Gevurah), and once judgement is passed one should see both litigants as righteous since they have accepted the truth (Tiferet). His colleague Shimon ben Shetach similarly teaches that a judge should be diligent in questioning witnesses in order to reach the correct verdict (Chessed), though a person should be restrained in their speech and careful with every word (Gevurah), lest their speech lead to the proliferation of falsehood (the opposite of Tiferet and Emet).

One can continue in this manner for the rest of the chapter and unravel the three-part structure of every phrase, with clear allusions to Chessed, Gevurah, and Tiferet each time. The very last verse mirrors the first, and gives the most explicit reference to these three Sefirot. In the beginning, Shimon haTzadik told us that the world stands on three things, and now at the end Shimon ben Gamliel tells us the world endures through three things: Din, Emet, and Shalom, three alternate names for Gevurah, Tiferet, and Chessed, respectively. In this way, we can understand each line of the first chapter of Avot on a far more profound level.

Shabbat Shalom!

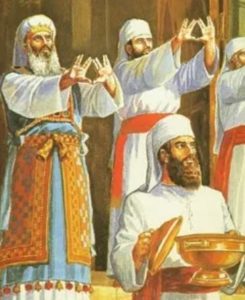

It is also why it is customary not to look directly at the kohanim when they relay the blessing. The hidden light may be far too intense, and might cause the observer’s eyes to dim (Chagigah 16a). The ancient mystical text Sefer haBahir (#124) adds that the kohanim put together their ten fingers in that unique arrangement in order to channel the energy of all Ten Sefirot. Elsewhere, we learn that the hands of the kohanim come together to roughly form an inner samekh, the only circular letter in the Hebrew alphabet, representing infinite cycles and endless blessings. Sefer haTemunah teaches that the proper shape of a samekh is a combination of a kaf and a vav. (The sum of the values of kaf and vav is 26, equal to the Tetragrammaton, God’s Ineffable Name.) Kaf literally means the “palm” of the hand, and the linear vav represents a shining ray of light. These are the hidden rays of light, the light of koh, emerging through the hands of the kohanim as they bless.

It is also why it is customary not to look directly at the kohanim when they relay the blessing. The hidden light may be far too intense, and might cause the observer’s eyes to dim (Chagigah 16a). The ancient mystical text Sefer haBahir (#124) adds that the kohanim put together their ten fingers in that unique arrangement in order to channel the energy of all Ten Sefirot. Elsewhere, we learn that the hands of the kohanim come together to roughly form an inner samekh, the only circular letter in the Hebrew alphabet, representing infinite cycles and endless blessings. Sefer haTemunah teaches that the proper shape of a samekh is a combination of a kaf and a vav. (The sum of the values of kaf and vav is 26, equal to the Tetragrammaton, God’s Ineffable Name.) Kaf literally means the “palm” of the hand, and the linear vav represents a shining ray of light. These are the hidden rays of light, the light of koh, emerging through the hands of the kohanim as they bless.