“Esau and Jacob” by Adolf Hulf (1919)

In this week’s parasha, Toldot, we are introduced to Jacob and Esau. The latter is born hairy and admoni, “red” (Genesis 25:25). There is only one other person in the entire Tanakh who is described the same way: King David (I Samuel 16:12). In fact, the Ba’al haTurim (Rabbi Yakov ben Asher, 1269-1343) comments that when the prophet Samuel came to anoint David and first saw him, he was surprised by his redness and immediately thought “this one is murderous like Esau!” However, Samuel then saw David’s soft and compassionate eyes and understood he is not like Esau. Nonetheless, it is certainly not a coincidence that Esau and David are described the same way, and that Samuel’s first impression of David was Esau. On a mystical level, their souls are deeply linked, and David served as the spiritual rectification of Esau.

When reading about the life of David in the Tanakh, we find that he was indeed quite similar to Esau. Both were physically strong and great warriors, with a long list of victims. Not longer after defeating the dreaded giant Goliath, David single-handedly struck down 200 Philistines. David’s hands were so bloody that God didn’t let him build the Jerusalem Temple! (I Chronicles 28:3) David would go on to raise an initial fighting force of 400 men (I Samuel 22:2), just as we read that Esau led an army of 400 warriors (Genesis 32:7). Even their armed forces were similar!

Another parallel is that both were voluntarily polygamous. I say voluntarily because Abraham and Jacob were polygamous, too, but not of their own choice. It was Sarah who orchestrated Abraham’s union with Hagar, while Jacob was tricked into marrying Leah when all he wanted was Rachel. All the other patriarchs and tribal fathers—including Isaac, Joseph, and Judah—were monogamous. (One tradition does suggest Benjamin had two wives. For more on that, see ‘The Names of the Torah’s Hidden Women’ in Garments of Light, Volume Two). David took on multiple wives by choice, as Esau had done long before him. And while she was truly his soulmate, we mustn’t forget the infamous incident with Batsheva. We therefore find that, like Esau, David had a strong physical desire. Unlike Esau, though, David was ultimately able to channel that energy in the right direction. He repented wholeheartedly—so much so that the Sages said he completely destroyed his yetzer hara—and was a godly man who spent much of his time in prayer, meditation, Torah study, and the composition of psalms praising God. This is who Esau was supposed to be.

Recall that in God’s original plan, Jacob and Esau were born as twins to fulfil twin roles: Jacob would be the one to bring goodness and light into the world, while Esau would combat evil and defeat darkness. This is why Jacob’s predisposition was to be “innocent, sitting in tents”, a scholar and teacher of the highest calibre, while Esau’s was to be “a skilled hunter, a man of the field” (Genesis 25:27). Each was given the abilities and talents needed to fulfil their task in rectifying the world and making it a dwelling place for the divine. Unfortunately, Esau was unable to use those blessings in the right way, and descended into a life of sin. This is where David came in, given the same “red” spark that Esau once carried. David was able to channel those blessings in the right way, and rectified the spark of Esau.

In the past, we already explored how David also carried the soul of Jacob. Within David was the embodiment of the twin roles. And because he was successful in both, he merited to establish the eternal Davidic dynasty, and become the progenitor of Mashiach. Mashiach, too, must fulfil both: to bring in the light and to defeat the darkness, restoring peace and unity to the globe. This involves not just teaching depths of Torah and punctiliously fulfilling mitzvot, but also confronting evil and fighting wars, which was originally the task of Esau:

In the same comment cited above, the Ba’al haTurim points out that the gematria of “Esau” (עשו) is 376, the same as shalom (שלום). He adds that “Esau” is ayin-shav (ע׳ שו), meaning he is equal to all 70 root nations of the world combined. We can learn from this that Esau had the strength to either destroy the entire world, or to establish peace upon it. He was unable to bring peace, and the task remains for Mashiach to complete. This might explain why Mashiach is described as “coming from Edom” (Isaiah 63:1). It doesn’t necessarily mean Mashiach will literally come from the ancient region of Edom (or Idumea) in southern Israel, or that he will come from the wider Western world which is referred to as “Edom” in rabbinic texts. It may really mean that Mashiach has a spiritual root coming from Edom, from Esau himself.

Now, we typically speak of two messiahs: a Mashiach ben Yosef that comes first, followed by a Mashiach ben David. Each of the two embodies one of the two tasks that date back to Esau and Jacob. Mashiach ben Yosef is called “the warrior messiah” who fights great wars and defeats evil. Mashiach ben David is the king who then establishes a better world and reigns in an era of peace and understanding. Ben Yosef and Ben David neatly parallel Esau and Jacob. Whether they are two distinct people or one person in two phases is subject to some debate and remains to be seen. Whatever the case, we continue to inch ever close to that time, and pray we witness it very soon.

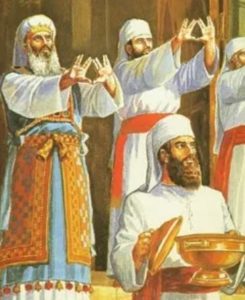

It is also why it is customary not to look directly at the kohanim when they relay the blessing. The hidden light may be far too intense, and might cause the observer’s eyes to dim (Chagigah 16a). The ancient mystical text Sefer haBahir (#124) adds that the kohanim put together their ten fingers in that unique arrangement in order to channel the energy of all Ten Sefirot. Elsewhere, we learn that the hands of the kohanim come together to roughly form an inner samekh, the only circular letter in the Hebrew alphabet, representing infinite cycles and endless blessings. Sefer haTemunah teaches that the proper shape of a samekh is a combination of a kaf and a vav. (The sum of the values of kaf and vav is 26, equal to the Tetragrammaton, God’s Ineffable Name.) Kaf literally means the “palm” of the hand, and the linear vav represents a shining ray of light. These are the hidden rays of light, the light of koh, emerging through the hands of the kohanim as they bless.

It is also why it is customary not to look directly at the kohanim when they relay the blessing. The hidden light may be far too intense, and might cause the observer’s eyes to dim (Chagigah 16a). The ancient mystical text Sefer haBahir (#124) adds that the kohanim put together their ten fingers in that unique arrangement in order to channel the energy of all Ten Sefirot. Elsewhere, we learn that the hands of the kohanim come together to roughly form an inner samekh, the only circular letter in the Hebrew alphabet, representing infinite cycles and endless blessings. Sefer haTemunah teaches that the proper shape of a samekh is a combination of a kaf and a vav. (The sum of the values of kaf and vav is 26, equal to the Tetragrammaton, God’s Ineffable Name.) Kaf literally means the “palm” of the hand, and the linear vav represents a shining ray of light. These are the hidden rays of light, the light of koh, emerging through the hands of the kohanim as they bless.