The essay below is an excerpt from the newly-released third volume of Garments of Light, available here (and now on Amazon here).

In parashat Tzav, we read about the many details of the sacrificial procedures. One of the strange practices described is that Moses took some of the blood of the sacrifices and smeared it on the right ear, the right thumb, and the right toe of the kohanim (Leviticus 8:23). This procedure was later replicated by the kohanim when purifying others (Leviticus 14). What is its significance? One beautiful explanation is given by Rabbeinu Bechaye (1255-1340).

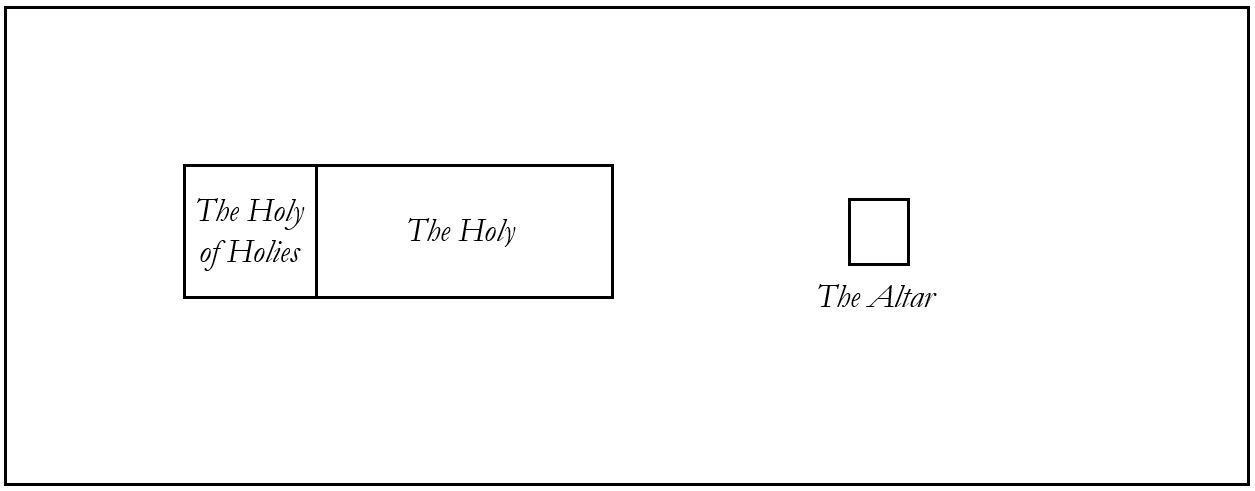

He begins by saying that the universe God created has three domains: the “world of angels”, the “world of spheres”, and the “lower world” which we inhabit. The highest world is mostly spiritual, while our lower world is mostly physical. In between is the cosmos, the “world of spheres”, referring to all the stars and planets. Moses constructed the Mishkan to mirror the three parts of Creation. The inner-most Holy of Holies corresponded to the world of angels; then the Holy space around it to the world of spheres; and the courtyard within the Mishkan to the lower world.

Outlines of the Mishkan, with the inner “Holy of Holies” (Kodesh haKodashim), the antechamber known as “the Holy” (Kodesh), and the outer courtyard (chatzer) with the sacrificial altar.

Similarly, since man is an olam katan, a microcosm of the universe, the human body also has three parts: head, upper body, and lower body. The head corresponds to the highest worlds, and hence this is where divine speech emerges from—speech containing the very powers of Creation, just as God spoke the cosmos into existence. The upper body, containing the heart that gives life to the whole body, corresponds to the world of spheres. Just as the heart is intertwined with the entire body, and circulates blood and nutrients all around, so too is the world of spheres entirely intertwined, with spheres orbiting around other spheres along precise paths in a dance held together by gravity (and other forces). Finally, the lower body from the waist down corresponds to the earthly world, as expected. With this in mind, we can better understand the procedure of the ear, thumb, and toe.

Rabbeinu Bechaye explains that the blood on the ear of the head corresponds to (and rectifies) the world of angels, the blood on the thumb of the upper body corresponds to the world of spheres, and the blood on the toe of the lower body corresponds to the lower world. He also mentions how these correspond to the soul. Recall that there are three major levels to the soul, the lowest being the animalistic nefesh, above it the more spiritual ruach, and the highest being the intellectual neshamah. The nefesh corresponds to the lower body, the ruach to the upper body, and the neshamah is seated in the brain. Thus, the sacrifice is able to atone for the entire soul, and for the entire body, as well as rectifying every aspect of the universe and of God’s Creation.

Souls and Senses

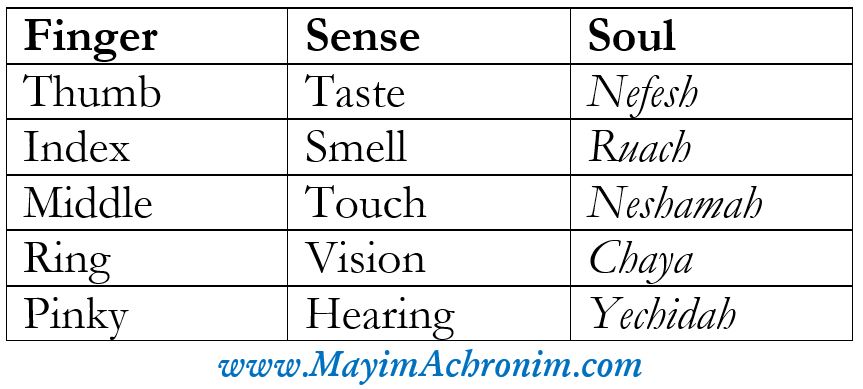

Rabbeinu Bechaye continues further on in his commentary to explain how the fingers are connected to the senses. He states that, of course, every organ and body part has a specific purpose, and nothing in God’s design is superfluous. (Classic case: for decades it was thought that the appendix is useless and an unnecessary “vestigial organ” that can be removed without a second thought. Today we know that the appendix does, in fact, play an important role in the digestive system.) The sense of taste requires the mouth and Rabbeinu Bechaye points out that people typically clean their teeth and mouth with their thumbs or thumb-nails. The sense of smell is in the nose, and people typically clean their nose with their index finger. The sense of touch is associated mostly with our hands, and people tend to feel things and sense textures by using their middle finger (or rubbing something between the thumb and middle finger). The ring finger is commonly used to clean and rub one’s eyes. Finally, the small pinky finger is the right size to clean the ear. In this way, every finger is connected to one of the five senses, and every finger can be used to clean the organ of that particular sense!

Rabbeinu Bechaye stops here, but there is more to be said. Although we typically speak of three main souls (nefesh, ruach, and neshamah), there are two more levels to the soul (sometimes described as the “neshamahs of the neshamah”) called chayah and yechidah. This complete array of five soul-levels further corresponds to the five fingers, and to the five senses. The short thumb is the lowest nefesh. As the lowliest “animal” soul, it sits separately from the other fingers. The nefesh is the one that always remains with the body, while the other parts are able to migrate. We learn, for instance, that when one is asleep the four higher souls can wander, while the nefesh always remains in the body (otherwise the body will not survive). Moreover, the Torah always says the nefesh is contained within the blood, and this is why meat must be drained of all blood before being consumed. We can now better understand why the blood of the sacrifice had to go specifically on the thumb of the person, and not any other finger.

The ruach part of the soul is the most “active”, and is the one that animates a person. Fittingly, it corresponds to the index finger, which is the most active and most-used of the digits. The biggest and longest of the fingers naturally corresponds to the biggest part of the soul, the neshamah. The ring and pinky fingers are the least-used, just as the chayah and yechidah are the loftiest and least accessible. The chayah is associated with one’s aura, the only part of the soul that might be perceived visually, so it neatly fits with the ring finger that is associated with eyes and vision. (The chayah plays an important, albeit subtle, role in the relationships and interactions between people so it is also appropriate that wedding rings are typically worn on this finger!)

The highest level of soul corresponds to the pinky finger and to the sense of hearing. That might explain why Moses’ final song to his people, the climax of his prophecy right before his passing, was Ha’azinu, literally charging the people “to listen”. And it might explain why the most powerful dictum in all of Judaism, the Shema, similarly commands the nation “to hear”. And it might further explain why the Talmud often introduces a new teaching with the words ta shma, “come and hear”. To summarize:

Left and Right

In Jewish thought, the right side is always associated with positivity and Chessed, kindness, while the left side is associated with Din and Gevurah, judgement and restraint. In mystical terms, the right side represents the realm of goodness and holiness, while the left side is commonly referred to as the Sitra Achra, the “other side”, the realm of impurity and evil. Indeed, we find that in many languages and cultures, the right side is associated with goodness and correctness (like being “right” in English) while the left is associated with evil. In Latin, for instance, the word for “left” is sinister! In Hebrew, there is a similar connection between the word “left”, smol, and the wicked angel that embodies evil, Samael. In Russian, something described as being “left” is a fake or a knock-off. Throughout history, being left-handed was perceived as somehow inappropriate, and left-handed people were often forced to use their right hands instead.

This is certainly unnecessary and, needless to say, there is nothing wrong with being left-handed! All humans were endowed with two hands, left and right, and on a mystical level they are simply meant to represent the two sides within Creation. This ties back to the gift of free will, with the hands standing as symbols of our ability to choose. The ultimate choice is whether to believe or not; whether to serve God and fulfil His commands, or not. Our Sages famously declare that “all is in the hands of Heaven [hakol b’yadei shamayim], except the fear of Heaven” (Berakhot 33b), while King Solomon taught that “death and life are in the hand of the tongue”, mavet v’chayim b’yad lashon (Proverbs 18:21). Over and over again, we see the hands used as symbols of choice between good and evil, between right and left, holiness and unholiness. Just as we have the power to use our hands, we have the power to subdue evil and act with goodness and kindness.

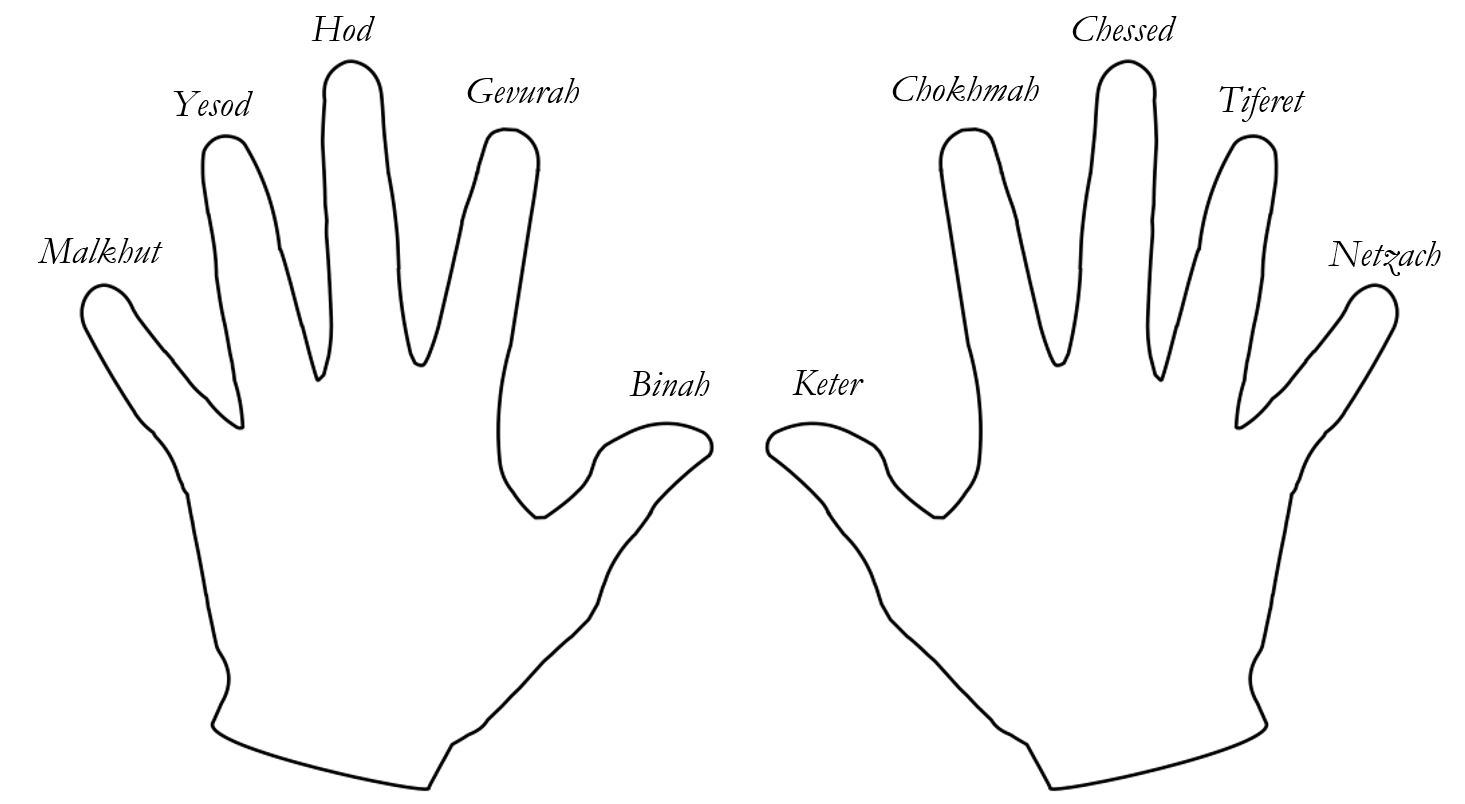

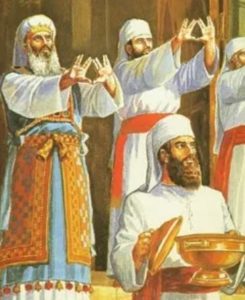

Thus, altogether the ten fingers of both hands embody all aspects of Creation. The ancient Sefer haBahir explains that the ten fingers correspond to the Ten Sefirot, as well as the Ten Utterances of Creation (see #124 and 138). Moreover, the Bahir says this is why kohanim have to arrange all ten fingers in that particular shape when blessing the congregation, thereby channeling all Ten Sefirot and activating all aspects of Creation. In later Kabbalistic texts, we are taught that the right thumb and index finger are Keter and Chokhmah, while the left thumb is Binah. The right middle finger is Chessed, the left index finger is Gevurah, the right ring finger is Tiferet, the left middle finger is Hod. The right pinky is Netzach, the left ring finger is Yesod, and the left pinky is Malkhut. The five Sefirot of Keter, Chokhmah, Chessed, Tiferet, and Netzach veer to the right, while the five Sefirot of Binah, Gevurah, Hod, Yesod, and Malkhut veer to the left. (We might learn from this yet another good reason for the common practice of wearing a wedding ring on the left ring finger, since it corresponds to Yesod, the domain of intimacy and reproduction.)

All of this can help us further appreciate the power of netilat yadayim and mayim achronim. The fingers link up to all aspects of our bodies, our senses, our souls, and even the cosmos at large. Thus, when we purify them correctly with life-giving waters, the unseen cosmic effects of these rituals are truly monumental.

What about the feet and toes?

Upper and Lower Worlds

The prophet Isaiah tells us that God created the upper worlds with His hands as He “measured the waters with a hand’s hollow, and established the Heavens with a little finger [zeret].” (Isaiah 40:12) The Earth, meanwhile, is described as God’s “footstool” (Isaiah 66:1). Thus, the hands and the “upper fingers” of the body represent the upper spiritual worlds, while the feet and the “lower fingers” of the body represent the lower material world. Indeed, the Zohar (I, 20b-21a) tells us that when we look at the reflection of the flame on our fingernails during Havdallah, we should meditate upon the higher spiritual worlds that the fingers of the hands represent. (More specifically, just as God told Moses that he could only see God’s “back”, but not His face, so too do we look only at the “backs” of the fingers, the fingernails!)

Interestingly, with this information we may be able to understand—from a mystical perspective—the difference in arrangement of fingers between the hands and the feet. On the hands, the biggest finger is the middle one, corresponding to the neshamah, while on the feet, the biggest finger is the toe, corresponding to nefesh. This further reinforces the notion that in this lower world (represented by the feet), the lower animalistic nefesh dominates. In the upper worlds (represented by the hands), it is the spiritual and lofty neshamah that is supreme. Unlike with the hands, the big digit on the feet is not separated from the rest of the toes—the nefesh seems to enjoy equal status with the other souls! On the hands, though, there is a clear distinction, mirroring the realities of the upper worlds.

Finally, the feet are grounded in the impurities of this lowly world. They are the coarsest parts of the body, and often the filthiest. The generation of Mashiach is compared to the feet, and the time before Mashiach is referred to as ikvot haMashiach, literally the “heels of the Messiah”. Like the feet, the people of this generation tend to be coarse and lowly, materialistic, lacking true spirituality. At the same time, however, the feet are among the strongest parts of the body, and can withstand tremendous weights and pressures. The feet can bear the greatest burdens, and only the feet can move us steadily onwards towards the final destination, the Messianic Age. Most beautifully, in the divine anatomy of the human body each foot contains exactly 26 bones, reminding us that God Himself is carrying us forward, as 26 is the exact numerical value of His Ineffable Name.

It is also why it is customary not to look directly at the kohanim when they relay the blessing. The hidden light may be far too intense, and might cause the observer’s eyes to dim (Chagigah 16a). The ancient mystical text Sefer haBahir (#124) adds that the kohanim put together their ten fingers in that unique arrangement in order to channel the energy of all Ten Sefirot. Elsewhere, we learn that the hands of the kohanim come together to roughly form an inner samekh, the only circular letter in the Hebrew alphabet, representing infinite cycles and endless blessings. Sefer haTemunah teaches that the proper shape of a samekh is a combination of a kaf and a vav. (The sum of the values of kaf and vav is 26, equal to the Tetragrammaton, God’s Ineffable Name.) Kaf literally means the “palm” of the hand, and the linear vav represents a shining ray of light. These are the hidden rays of light, the light of koh, emerging through the hands of the kohanim as they bless.

It is also why it is customary not to look directly at the kohanim when they relay the blessing. The hidden light may be far too intense, and might cause the observer’s eyes to dim (Chagigah 16a). The ancient mystical text Sefer haBahir (#124) adds that the kohanim put together their ten fingers in that unique arrangement in order to channel the energy of all Ten Sefirot. Elsewhere, we learn that the hands of the kohanim come together to roughly form an inner samekh, the only circular letter in the Hebrew alphabet, representing infinite cycles and endless blessings. Sefer haTemunah teaches that the proper shape of a samekh is a combination of a kaf and a vav. (The sum of the values of kaf and vav is 26, equal to the Tetragrammaton, God’s Ineffable Name.) Kaf literally means the “palm” of the hand, and the linear vav represents a shining ray of light. These are the hidden rays of light, the light of koh, emerging through the hands of the kohanim as they bless.