This week’s parasha (outside of Israel) is Korach, about the eponymous revolutionary who sought to change the social structure of the nation in the Wilderness. Korach infamously accused Moses and Aaron of consolidating all the power for themselves and their family. After all, the supreme leader was Moses, the high priest was his brother Aaron, the military chief of staff was best friend Joshua, and the chief of the Levites was cousin Elitzafan. The final straw may have been when, at the end of last week’s parasha, God promised the kohanim numerous privileges for their priestly service (Numbers 15). Understandably, many did not like this. Korach argued that “we are all holy”, not just the priests. As Rashi comments, Moses did agree with Korach in principle, however, the reality is that people are not the same. Moses replied to Korach with something often echoed today by those on the political right against those on the left: equality does not mean sameness.

Interestingly, the Zohar (I, 17a) tells us that Korach represented the left side of Gevurah, while Moses and Aaron stood on the right side of Chessed. It seems the divide between Left and Right already existed over three millennia ago! There is an important message here for today: we would actually expect the platform of Korach to be on the side of Chessed, “kindness”, the side of unlimited giving—after all, they want everyone to be equal and the same and receive the same benefits. And we would think that Moses should be on the left side of Gevurah, “severity”, separation, and restraint. Yet, the Zohar says it is exactly the opposite. Trying to make everyone the same is not an act of kindness at all, and will ultimately fail. The real Chessed is the position of Moses and Aaron: we are indeed equal, and should have equal opportunities, but people are not the same, and sameness cannot be imposed on society.

The total failure of the Soviet Union proved the futility of attempting to impose sameness in the form of communism and excessive socialism. The kibbutz movement in Israel was closer to the original communist ideals, and was voluntary, not imposed. It enjoyed far more success than the USSR for a time, but ultimately floundered anyway. Such utopian societies sound good in principle, but never work in reality. As the old saying goes, one who is not a socialist at age 20 has no heart, and one who is still a socialist at age 40 has no brain. Still, Jews have played prominent roles in communist history, and antisemites often accuse Jews of pushing socialism. (Ironically, antisemites also accuse Jews of being greedy capitalists at the same time!) What is the actual Jewish approach to proper government and social structure? How does the Torah envision the ideal society?

Three Branches of Government

In the Wilderness, Moses was the leader of the nation but bore no special title. His successor was not one of his sons, but Joshua, who hailed from a different tribe altogether. Joshua’s successor was also unrelated to him, Othniel of the tribe of Yehuda. Such “judges” were not appointed or anointed, and rose to power through their merits and the recognition of their fellows, as well as the blessing of God. The first several hundred years of Jewish history reflect a simple meritocracy. (Some scholars have called this type of rule by judges a “kritocracy” or “kritarchy”.) The Torah served as the constitution and the law of the land. It was further upheld by a council of seventy elders, first appointed by Moses, later giving rise to the Sanhedrin. It was a difficult time, though, as the Tanakh makes clear, and a stronger governing body soon became necessary. The Torah did state that a king may be selected, but it took over 400 years until Israel officially had one. It was only at the time of King David that the ideal Torah government was finally realized.

Today, we are familiar with the three branches of government found in most Western states: an executive (the president or prime minister), a legislative (such as a parliament or senate), and a judicial (the supreme court). Israel similarly had three branches: the king was the executive, the Sanhedrin was part legislative and part judicial, and there was a priesthood that played an active role in government and society. We see a semi-separation of church and state, too, since a priest was forbidden from being a king. (Centuries later, when the Hashmonean kohanim of Maccabee fame took over the kingship, it set off a massive revolt among the masses—and may have resulted in the final split between the Pharisees and Sadducees, as explored here.) Nonetheless, the king was expected to abide by Torah law, which places limits on his powers and largesse, and includes a distinct mitzvah for a king to write a Torah scroll of his own, which would be symbolically bound to his arm. It appears that the ideal Torah government is something like a theocratic constitutional monarchy.

The ancient Greeks were the first to formally explore the philosophy of government. They generally spoke of three main forms of government: a monarchy (rule by one), an aristocracy (rule by a few elites), or a democracy (rule by many). Aristotle, for instance, gave pros and cons of each type, and didn’t specifically say which form of government is the absolute best. We can see how the Torah government fuses the best elements of all three: there is a singular king, and a distinct aristocratic class in the kohanim, but also a Sanhedrin to which anyone could aspire to and participate in. Even the poorest man and a foreigner, like Hillel the Elder, could reach the top of the Sanhedrin and become nasi, “president”.

It was the Sanhedrin that had the most impact on daily life and law. The king’s primary role was militaristic and diplomatic, to defend the nation and to deal with foreign affairs. The priesthood’s role was, of course, spiritual and Temple-oriented. The Sanhedrin was the legal department, and in charge of day-to-day affairs. When the Jewish kingdom and the Jerusalem Temple were destroyed by the Babylonians, putting aside the monarchy and the priesthood, the elders of the Sanhedrin received even more authority. They became the dominant governing body. Upon returning to the Holy Land seventy years later, under Persian dominion and with no Jewish king, an even larger governing body was necessary: the Knesset haGedolah.

Knesset: Past, Present, and Future

At the start of the Second Temple era, the Jewish government was run by the Anshei Knesset haGedolah, the “Men of the Great Assembly”. This was a legislative body made up of 120 prominent leaders. Of the 120, roughly 85 were sages, Levites, and priests (a list of their names is given in Nehemiah 10:2-28), while the rest were the last generation of true prophets, among them Zechariah, Haggai, and Malachi. It isn’t clear whether the Knesset haGedolah lasted only for that one generation of Jewish exiles returning to Israel, or continued for several generations before dissolving and being replaced by the regular Sanhedrin of 70.

When Jewish exiles once again returned to rebuild their country in the last century, the model for a new parliament for the new State of Israel was the ancient Knesset haGedolah. The person who proposed this was Rabbi Zerach Warhaftig (1906-2002). He was born in what is now Belarus to a Religious Zionist family associated with the Mizrachi movement. The son of a rabbi, he took up rabbinic studies himself, and afterwards studied law in Warsaw and at the Hebrew University. It was Warhaftig who masterminded the famous move of the Mir Yeshiva to Shanghai to save it from Nazi destruction. Warhaftig played an active role in the establishment of the State of Israel, too, and was one of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence. He said that the new Israel must seek every possible means to be connected to the old, “since we are renewing and resurrecting an ancient state”. He argued that since “the first parliament after the first return to Zion was called the Knesset haGedolah”, then the new one should also be called the Knesset and also have 120 members. His advice was taken, and the following year, on Tu b’Shevat of 1949, the first Knesset convened, with Warhaftig sworn in as one of its first members. (He was part of the religious alliance that included Mizrachi and Agudat Yisrael. Warhaftig went on to serve as deputy minister of religion, and then minister of religion, until 1974!)

Today, like other Western democracies, the State of Israel has three branches of government: the executive under the prime minister (and a mostly-symbolic president), the legislative Knesset, and the judicial supreme court of 15 appointed judges, commonly known as Bagatz, an acronym for Beit Mishpat Gavo’ah LeTzedek, “supreme court for justice”. This is not to be confused with a traditional and religious court of justice, the badatz, or beit din tzedek. For now, the Israeli government is not a Torah government, and we all await the return of the Davidic dynasty, the re-establishment of the Sanhedrin (one of the key roles of Mashiach, as per Yalkut Shimoni II, 429), rebuilding of the Temple, and return of the priesthood to run it. Even that, though, will be temporary, perhaps lasting three generations (see Sanhedrin 99a). After this transition period, evil will have been entirely eliminated, all rectifications completed, and people will not require governing. God Himself will rule over the entire world, as Zechariah (14:9) prophesied: “And God shall be king over all the Earth; on that day, God will be one and His name one.”

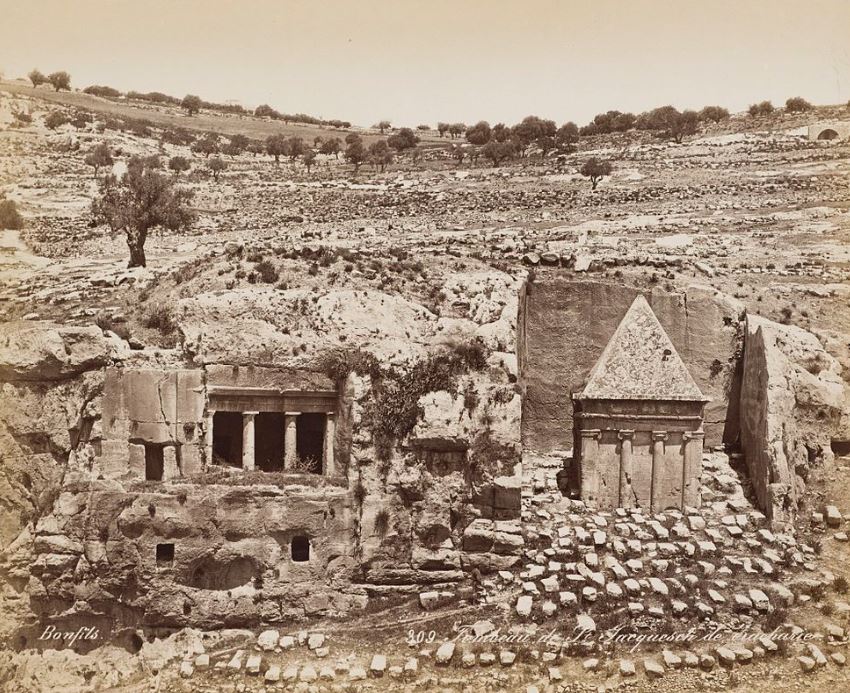

Above: the new building of the Israeli Supreme Court, with the Knesset building in the background. Clearly visible is a pyramid with all-seeing-eye, frequently the subject of many Illuminati conspiracy theories. The official explanation is that the Supreme Court building includes elements of all Jewish and Holy Land history, and this pyramid feature is modeled on the 1st century Tomb of Zechariah uncovered in Jerusalem’s Kidron Valley, an 1870 photo of which is below: