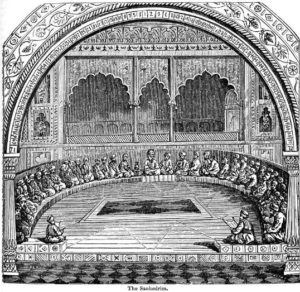

This week’s parasha begins with the command to appoint shoftim v’shotrim, “judges and officers” who will enforce the law. The Torah warns that judges must not pervert justice, show favouritism, or accept bribes (Deuteronomy 16:19). If there is some kind of civil dispute, the Torah instructs the nation to turn to the “kohanim, Levites, and judges who will be in those days, and you shall inquire, and they will tell you the words of judgement.” (Deuteronomy 17:9) From this the Sages derive that the Sanhedrin, the supreme court of the Jewish people, must contain a mix of all three types of Jews: kohanim, levi’im, and Israel. What exactly is the Sanhedrin? When did it emerge, and why is it referred to by a Greek word?

The Seventy Elders

In Numbers 11, we read how Moses had grown tired of leading the people on his own, and asked God for some assistance. God replied:

“Assemble for Me seventy men of the elders of Israel, whom you know to be the people’s elders and officers, and you shall take them to the Tent of Meeting, and they shall stand there with You. I will come down and speak with you there, and I will increase the spirit that is upon you and bestow it upon them. Then they will bear the burden of the people with you so that you need not bear it alone.” (Numbers 11:16-17)

This is the earliest origin of the Sanhedrin, the council of seventy judges that lead the Jewish people by majority rule. Moses served on top of the council as nasi, “president”, bringing the total number of judges to 71, which would prevent a 35-35 split in the decision-making process.

The Sanhedrin had a variety of roles and powers. One of these was proclaiming a new month at the first sighting of a new moon. This would determine the dates of upcoming holidays. Another was to institute various “fences”, additional prohibitions designed to protect the integrity and observance of the Torah. The Sanhedrin also dealt with difficult civil cases, like a Supreme Court, and had the power to try capital cases, though death sentences were extremely rare. (The Mishnah [Makkot 1:10] famously states that a Sanhedrin which sentenced someone to death once in seven years, or even just once in seventy years, was described as a “murderous” or “bloody” one.)

The Sanhedrin had a variety of roles and powers. One of these was proclaiming a new month at the first sighting of a new moon. This would determine the dates of upcoming holidays. Another was to institute various “fences”, additional prohibitions designed to protect the integrity and observance of the Torah. The Sanhedrin also dealt with difficult civil cases, like a Supreme Court, and had the power to try capital cases, though death sentences were extremely rare. (The Mishnah [Makkot 1:10] famously states that a Sanhedrin which sentenced someone to death once in seven years, or even just once in seventy years, was described as a “murderous” or “bloody” one.)

While the Sanhedrin is generally referred to as a council of seventy elders, in some places it is described as having 71 or 72 judges. Some say the extra judge refers to the av beit din, the vice-president or “speaker of the house”. Others refer to this person as the mufla, the top judge who can cast the final vote or put an end to a particular debate (see Shir HaShirim Rabbah 7:3). In the Wilderness, this role was fulfilled by Joshua, the vice-president. According to the Zohar on this week’s parasha (III, 275b), it was Aaron the high priest.

How do we reconcile the various sources that speak of the Sanhedrin as either having 70, 71, or 72 judges? The number of elders was certainly seventy—which is why the Sanhedrin is referred to as a court of seventy—plus the nasi, which makes for 71. There has to be 71 to prevent that split decision. In that case, how could there be 72? This would also create a possibility for a split! I think the most likely answer is that the nasi was usually too busy to preside over the Sanhedrin and be the mufla, so his vice, the av beit dein, was there instead to fulfil that role. This is why he is called the av beit din, suggesting that he is the “father” or head of the court in place of the president.

That was precisely the case with Moses, who had Joshua preside over the elders while he was busy with other matters. This is in line with the foundational teaching that Moses would receive the law from God, teach it to Joshua, then Joshua would teach it to the Sanhedrin of seventy elders. Moses generally did not preside over the Sanhedrin himself, but had Joshua serve in his place as the mufla. This explains the incident with Eldad and Meidad which follows the appointment of the first Sanhedrin (Numbers 11).

Recall that Eldad and Meidad were two members of the Sanhedrin who prophesied negatively of Moses, causing Joshua to run to Moses and tell him what happened (v. 27-28). Joshua had to run over to Moses because Moses was not himself present at the Sanhedrin! Therefore, while at any given time there were 72 people who were part of the Sanhedrin and had the power to cast a vote, there would only be 71 people voting during an actual session, the 71st being either the nasi or av beit din, serving as the mufla.

This also explains why the nasi and av beit din were called a zug, “pair”. The earliest rabbinic era is referred to as the time of zugot, when there was always a pair of leaders. The first pair was probably Shimon haTzadik (the last of the Knesset HaGedolah, the “Great Assembly” of 120 prophets and sages who revived Judaism in Israel at the start of the Second Temple era, following the Babylonian exile) and Antigonus of Socho. After them were Yose ben Yoezer and Yose ben Yochanan. The last of the zugot were Hillel and Shammai. Henceforth, the nasi was generally a direct descendant of Hillel (who was himself a descendant of King David), while the office of the av beit din appears to have fallen from significance (a notion possibly supported by a discussion in Moed Katan 17a), ending the era of zugot.

The First Sanhedrin

The term Sanhedrin comes from the Greek synhedrion, “sitting together”. In ancient Greece, the synhedrion was a local council of ruling elders that debated matters and ruled by majority vote. Like almost everything else, the Romans adopted this democratic institution from the Greeks. The Greek historian Polybius (c. 200-118 BCE) referred to the Roman Senate as a synhedrion. And so, when the Greeks ruled over Israel they naturally described its Jewish council of elders as a synhedrion, too, and the name stuck. Josephus records that the Romans established five synhedria in Israel in 57 BCE (Antiquities of the Jews, xiv. 5). This is in line with the Sages’ ruling that every town could have a smaller “Sanhedrin” of 23 judges. Josephus also speaks of an earlier gerousia in Jerusalem, another Greek word for a ruling council that comes from the Greek root for “elders” (ibid. xii. 3). The first gerousia was established by the legendary Lycurgus in Sparta. (We’ve written in the past about the once-close relationship between Jews and Spartans.)

Back in 67 BCE, the Hasmonaean queen of Israel, Salome Alexandra (Shlomtzion) passed away. She was the sister of the great Mishnaic sage Shimon ben Shetach, who also served as nasi of the Sanhedrin. Unfortunately, her husband was the cruel Alexander Yannai, who had persecuted the rabbis and shut down the Sanhedrin. When he was out of the picture, Salome took over the reins, summoning the exiled rabbis (including her brother) back from Egypt and reopening the Sanhedrin. She is also credited with instituting the ketubah. When she died, her two sons fought for the throne, starting a nasty civil war. Unable to resolve the conflict on their own, they invited the Romans to help settle it for them.

Back in 67 BCE, the Hasmonaean queen of Israel, Salome Alexandra (Shlomtzion) passed away. She was the sister of the great Mishnaic sage Shimon ben Shetach, who also served as nasi of the Sanhedrin. Unfortunately, her husband was the cruel Alexander Yannai, who had persecuted the rabbis and shut down the Sanhedrin. When he was out of the picture, Salome took over the reins, summoning the exiled rabbis (including her brother) back from Egypt and reopening the Sanhedrin. She is also credited with instituting the ketubah. When she died, her two sons fought for the throne, starting a nasty civil war. Unable to resolve the conflict on their own, they invited the Romans to help settle it for them.

The Roman general Pompey (later to rule Rome as part of the First Triumvirate) had just finished a war in nearby Syria and Armenia. Long story short, instead of settling the dispute between the Hasmonean brothers, Pompey decided to keep Israel for himself. After a short siege on Jerusalem in 63 BCE, Pompey triumphed and entered the Temple. He treated his new subjects relatively well, and left them with a semi-autonomous government. Pompey’s general Aulus Gabinius divided the former Hasmonean kingdom into five provinces, and set up a smaller sanhedrin in each one, thus temporarily diminishing the authority of the nasi and the Great Sanhedrin in Jerusalem. In 37 BCE, Herod took over as King of Judea, and also sought to suppress rabbinic authority wherever possible. After he died in 4 BCE, the authority of the Sanhedrin and nasi slowly started to make a comeback. The Romans recognized the Great Sanhedrin of Jerusalem as the official lawmaking body of Israel, and the nasi as the patriarch and representative of the Jews.

During the Great Revolt, the president of the Sanhedrin at the time, Shimon ben Gamliel (great-grandson of Hillel) was executed by the Romans shortly before the Temple was destroyed in 70 CE. Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai took over the top job in his place, and saved the Sanhedrin from destruction. In the well-known story, Rabban Yochanan pretends to be dead and is carried out of besieged Jerusalem in a coffin. He then goes out to meet the Roman general Vespasian. In one version of the story, Vespasian already knows of Rabban Yochanan’s greatness and wants to grant him one wish. In another version, Rabban Yochanan greets Vespasian with a “Hail Caesar” and Vespasian is about to punish him for treason before a messenger arrives saying Vespasian had just been elected Rome’s new emperor. The impressed Vespasian then decides to grant Rabban Yochanan one wish. The wish is to spare Yavneh, for this is where the Sanhedrin had previously been relocated (more on this below). The wish is granted.

Interestingly, some scholars have proposed that there were two Sanhedrins in ancient Israel: a political one and a religious one. It is possible that the head of the political Sanhedrin was the nasi, whereas the head of the religious Sanhedrin, or beit din, was the av beit din—hence the need for zugot, pairs. This may also explain why sometimes the Sanhedrin is described as meeting in the Temple’s lishkat hagazit, “hall of hewn stone”, and other times in the lishkat parhedrin, hall of the high priest. Some believe the political Sanhedrin was always led by the high priest, who also served as nasi, hence the gathering in his chambers. The term parhedrin appears to come from a Roman title for an elected official. According to this theory, when the Temple was destroyed—and Judea’s autonomy put to an end—the political Sanhedrin ceased to exist. The religious Sanhedrin, or beit din, continued to function in Yavneh, now with both a nasi and an av beit din! (This theory may also explain why henceforth the pair were no longer referred to as a zug, and the era of zugot was deemed over.)

The Last Sanhedrin

In 80 CE, ten years after the Great Revolt when things had calmed down somewhat, the post of nasi was once more filled by a descendant of Hillel, Rabban Gamliel II. He moved the Sanhedrin to a new location, the town of Usha in the Galilee. Before the end of his tenure, Rabban Gamliel had to relocate the Sanhedrin back to Yavneh once more.

The Sanhedrin was disbanded during the Bar Kochva Revolt, then reformed in Usha around 142 CE under the leadership of Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel II. His son was the great Rabbi Yehuda haNasi, compiler of the Mishnah. The Sanhedrin would move from place to place several more times before finding a permanent home in Tiberias around 193 CE. Unfortunately, the court slowly lost power and prestige, and its authority was increasing curtailed by the Roman overlords. Finally, the emperor Theodosius I banned the Sanhedrin entirely around 380 CE. It was then that Hillel II, the nasi, fixed the Jewish calendar for good so that the new months would no longer rely on proclamation from the Sanhedrin. This is considered to be the last edict of the Sanhedrin.

The office of nasi—as representative of the Jews—continued for a little while longer, and occasionally secret gatherings of the Sanhedrin took place. Around 429 CE, Theodosius II formally banned the office of nasi as well, and had the traditional tax levied on Jews to support the nasi be switched to a tax to support his own royal treasury. The last president was Gamliel VI. Many Jews migrated across the border to the Persian Sassanian Empire where the king at the time, Bahram V, was the son of a Jewish queen, Shushandukht.

The ancient city of Mahoza was near the Sassanian capital of Ctesiphon and currently al-Mada’in in Iraq.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t long after Bahram and Shushandukht that persecutions against the Jews began once more in the Sassanian realm. In 469 CE, King Peroz I shut down all Jewish academies and oppressed the rabbinic authorities. This development was partly responsible for the close of the Talmudic period. Interestingly, the Jewish leader (reish galuta) in Sassania at the time was Mar Zutra II, who eventually organized a revolt in 495 CE and managed to establish an independent Jewish state in Mahoza! The state survived for seven years before being crushed by the Persians. Mar Zutra II was crucified. His son, Mar Zutra III—according to legend born on the same day his father was killed—was saved and taken to Israel. When he turned 18, Mar Zutra III was appointed reish pirka, the head of a newly-re-established, secret Sanhedrin in Tiberias that didn’t last very long. There has been no Sanhedrin since, though several groups of rabbis in the past have tried to re-establish it.

Who is a “Rabbi”?

One of the roles of the Sanhedrin was to facilitate semikhah, “ordination”, of new rabbis. This ceremony could only be done when a Sanhedrin was around, and only in the land of Israel. This is why the Sages of the Babylonian Talmud are not called “rabbi” but simply “rav”. For example, if you read about “Rabbi Yehudah” without any other description, it is probably talking about Rabbi Yehudah bar Ilai, a student of Rabbi Akiva, who was ordained during the Bar Kochva Revolt (Yevamot 62b). If you read about “Rav Yehudah”, however, it is most likely referring to the Babylonian sage Yehudah ben Ezekiel. He was not called “rabbi” since he was not from Israel and did not receive formal semikhah.

After the Sanhedrin was put to an end at the end of the fourth century, no official ordination of new rabbis was possible. The vast majority of Jewish leaders went by the title “rav”, for the Sages state that any teacher of Judaism can go by this title (see, for instance, Avot 6:3). The term “rabbi” only started to make a comeback in in the 13th and 14th centuries, starting in Europe. This came as a response to the first universities conferring degrees and titles. Ashkenazi institutions started to do the same, equating ordination with a university-type graduation and conferring the title of “rabbi”. Sephardic authorities generally rejected this development, and refused to use the title of “rabbi”. For a long time afterwards, Sephardis continued to use the title rav, or hakham, “sage”. Eventually, the term “rabbi” became widespread enough that Sephardis started using it, too. This was further supported by a Sephardi attempt at reviving the ancient Sanhedrin.

In 1538 CE, Rabbi Yakov Berav (1474-1546) gathered twenty-five rabbis in Tzfat to re-establish the Sanhedrin. Berav was born in Toledo, Spain and settled in Fez, Morocco after the Expulsion of 1492. He became the chief rabbi of Fez, but eventually left and ended up in Egypt. In 1535, after becoming very wealthy, he settled in Tzfat which had a booming Jewish community thanks to the work done by Rav Yosef Saragossi.

For a number of reasons (mainly facilitating the return of Conversos into the Jewish fold), Berav wanted to bring back the Sanhedrin. Jewish law states that if a large gathering of rabbis in the Holy Land unanimously agrees to confer semikhah upon a worthy individual, the ceremony could be done and the ordination process revived (see Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot Sanhedrin 4:11). That individual would officially be a “rabbi” and could then ordain other rabbis. Berav gathered twenty-five prominent sages who all agreed to appoint him as head of a new Sanhedrin. Berav thus became the first official “rabbi” in a thousand years. Or so he thought.

The chief rabbi of Jerusalem at the time, the Ralbach (Rabbi Levi ibn Habib, c. 1480-1545) was not amused. He did not agree to Berav’s plan, which means there was no unanimous decision in the Holy Land on reviving the Sanhedrin. Berav countered by saying total unanimity is impossible; the law requires only a majority. Ralbach then pointed out that if the Sanhedrin really had been established, they would have to start proclaiming the new months based on the new moon sighting—which they did not do—automatically invalidating their supposed “Sanhedrin”. Berav disagreed, and saw no reason why the Sanhedrin must deal with calendar issues. He thought he could appease the Ralbach by making him the first to receive semikhah. Instead, Ralbach took it as an insult.

The Turks weren’t thrilled with Berav either, accusing him of plotting to re-establish a Jewish kingdom and overthrowing Turkish rule. Fearing for his life and freedom, Berav had to flee back to Egypt. Before he did that though, he made sure to ordain Rabbi Yosef Karo (1488-1575, who composed the Shulchan Arukh) and Rabbi Moshe di Trani (1505-1585) and possibly several others (including Rabbi Abraham Shalom, Rabbi Yosef Sagis, and Rabbi Israel di Curiel). These rabbis went on to ordain other rabbis. Rabbi Karo ordained Rabbi Moshe Alshich (1508-1593), who then ordained Rabbi Chaim Vital (1543-1620, primary disciple of the Arizal). With all these Sephardi authorities receiving semikhah and being called “rabbi”, the title became more and more widespread—even among those with no connection to the soon-defunct Sanhedrin of Berav.

Today, the term “rabbi” has become the norm, even among denominations and congregations that are not halakhic, and sometimes not even theistic! Suffice it to say that the title no longer carries the weight it once had. Perhaps it is worth mentioning a teaching at the very end of Tosefta Eduyot which states that the title “rabbi” is a great one, and greater still is the title “rabban”, but the greatest title of all is being referred to simply by one’s name. Your title is not what should make you great; your own name should be great! Indeed, we find that the greatest sages, such as Hillel and Shammai, did not have any title at all.

A New Sanhedrin?

The Midrash (Yalkut Shimoni, Isaiah 429) summarizes the late history of the Sanhedrin:

“[For He has brought down those that dwell on high, the lofty city] laying it low, laying it low even to the ground, bringing it to the dust.” [Isaiah 26:5] Said Rabbi Yochanan: “The Sanhedrin went through ten exiles: from lishkat hagazit to the “markets”, and from the “markets” to Jerusalem. From Jerusalem to Yavneh, and from Yavneh to Usha. From Usha to Shafra’am, and from Shafra’am to Beit She’arim. From Beit She’arim to Tzippori [Sepphoris], and from Tzippori to Tiberias, which is the “lowest” of them all… and from there it is destined to be redeemed, as it is written, ‘Shake off your dust, arise…’” [Isaiah 52:2]

The Midrash says that first the Sanhedrin left its place in the Temple complex and would convene in the markets of the Temple Mount. The Talmud (Shabbat 15a) adds that this happened forty years before the Temple was destroyed, when the Romans stripped the Sanhedrin of its ability to try capital cases. The Sanhedrin was then further removed from the Temple Mount and convened elsewhere in the city of Jerusalem. Sometime before the Temple’s destruction, it moved to Yavneh, then to Usha, and a number of other places before its last location in Tiberias. It is then prophesied, based on verses in Isaiah, that the new Sanhedrin will be re-established in the times of Mashiach specifically from Tiberias where it last convened.

Today, all the rabbinic authorities agree that we are living in the “footsteps of Mashiach”. And so, after many years of deliberation and planning, in 2004 a large group of rabbis gathered in Tiberias to re-establish the Sanhedrin. Because the law requires a majority of Israel’s rabbis to agree to such a move, a large marketing campaign was first launched, spreading over 50,000 pamphlets to Israel’s rabbis. Both the top Ashkenazi and Sephardi gedolim at the time, Rav Elyashiv and Rav Ovadia, respectively, agreed to re-establish semikhah, and agreed on who would be the person to get the first ordination, though they did not vocally support a new Sanhedrin, nor did they speak much about the whole initiative in public.

The first person to be conferred semikhah was Rabbi Moshe Halberstam (1932-2006). Rabbi Halberstam was selected because he was a renowned scholar and rosh yeshiva, and more importantly, because he was a rare symbol of unity who had great relationships withing his Ultra-Orthodox community as well as with the wider Modern Orthodox and Religious Zionist world. Rabbi Halberstam accepted the ordination, though not without great controversy within the Hasidic communities he was a part of. He then ordained Rabbi Dov Levanoni (1922-2019), after which he no longer had anything to do with the initiative. Rabbi Levanoni was a Holocaust survivor and an elder within Chabad, and the world’s top expert on the Temple. (His first yahrzeit is tonight.) Rabbi Levanoni then ordained Rabbi Tzvi Idan, a vocal activist who still strives to increase Jewish sovereignty over the Temple Mount.

It was Rabbi Tzvi Idan who gathered over 100 rabbis in Tiberias in October 2004 to formally re-establish the Sanhedrin. He ordained 70 rabbis, and they appointed him the temporary nasi. About a year later, the Sanhedrin unanimously selected Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz (1937-2020, who passed away two weeks ago) as the new nasi. He accepted reluctantly, saying he would only be a transitional figure, and ultimately resigned in 2008. The new “Sanhedrin” has gained little acceptance or recognition, and hasn’t been able to accomplish much at all. We must continue to wait for Mashiach himself to come and properly re-establish the ancient council of elders that first began with Moses so long ago.

Pingback: What are the True Borders of Israel? | Mayim Achronim

Pingback: The Little-Known Purpose of Deuteronomy | Mayim Achronim

Pingback: The Ideal Torah Government | Mayim Achronim