This week’s parasha, Bo, describes the final three plagues that God brought upon Egypt. There is an allusion to this in the very name of the parasha, since the gematria of “Bo” (בא) is 3. It is not a coincidence that the Torah divides the Ten Plagues between two parashas, seven in last week’s and three in Bo. In fact, all things that are “Ten” in the Torah (such as the Ten Utterances of Creation, the Ten Commandments, or the Ten Trials of Abraham) follow the same pattern of 7 and 3. The pattern is based on the Ten Sefirot, where there are three higher mochin, “mental” faculties, above the seven lower middot, “emotional” faculties or character traits. Since the Ten Sefirot permeate all aspects of Creation, this same pattern reveals itself in many places.

In the Utterances of Creation, for instance, the first three Utterances brought forth the cosmos and the Heavens, while the remaining seven formed this lower Earth and its inhabitants. In the Ten Commandments, the first three are mitzvot dealing directly with God Above, while the remaining seven deal with what goes on down here below. In nature, too, we see seven major visible colours in the light spectrum and hear seven major musical notes on the scale. (Mystical texts hint to those three “higher” colours and notes that we might experience in a future world.)

On that note, seeing and hearing are the most important senses, and allow us to make sense of the world far more than touch, taste, or smell. In fact, the latter three are not really necessary when it comes to most forms of learning; it is through seeing and hearing that we grow wiser. Not coincidentally, in rabbinic texts there are two expressions used to introduce a teaching: ta chazei (“come and see”) and ta shma (“come and hear”).

Having said that, if Creation is built on a pattern of 3 and 7, we might expect to see the same when it comes to that human senses. And we do. Although people generally speak of 5 senses, there are actually 10. (This is also reflected in the Ten Sefirot, which are grouped into Five Partzufim, “faces”. It is why we see many fives in Creation, too, including the five levels of the soul and the five books of the Torah. We will leave this aside for now.) In addition to seeing, hearing, touching, tasting, and smelling:

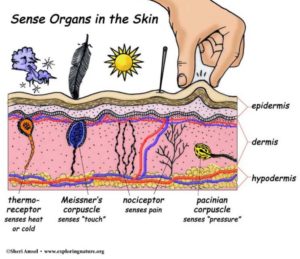

There is a sense of temperature, which uses unique cellular structures called thermoreceptors. There is a sense for pain—not to be confused with touch—again using unique cellular structures called nociceptors. (The sense of touch is mainly produced by a family of mechanoreceptors, such as the Meissner or Pacinian corpuscles in the diagram on the right). Interestingly, there is a disorder called congenital analgesia where a person is unable to feel pain, even though their sense of touch is generally normal.) We sometimes forget that we also have a sense of time, as well as a sense of space, ie. we know when we are upside down or lying down, stationary or in motion. This latter sense is called proprioception, or kinesthesia. And finally, there is the sense of self; being conscious and aware of one’s own existence. It involves sensing one’s own inner environment (including what scientists call introception), one’s emotions and thoughts, as well as that voice in a person’s head. (It has been pointed out by many a philosopher that the voice in your head is not actually you. You are perceiving thoughts, too, and are capable of reflecting on them!)

There is a sense of temperature, which uses unique cellular structures called thermoreceptors. There is a sense for pain—not to be confused with touch—again using unique cellular structures called nociceptors. (The sense of touch is mainly produced by a family of mechanoreceptors, such as the Meissner or Pacinian corpuscles in the diagram on the right). Interestingly, there is a disorder called congenital analgesia where a person is unable to feel pain, even though their sense of touch is generally normal.) We sometimes forget that we also have a sense of time, as well as a sense of space, ie. we know when we are upside down or lying down, stationary or in motion. This latter sense is called proprioception, or kinesthesia. And finally, there is the sense of self; being conscious and aware of one’s own existence. It involves sensing one’s own inner environment (including what scientists call introception), one’s emotions and thoughts, as well as that voice in a person’s head. (It has been pointed out by many a philosopher that the voice in your head is not actually you. You are perceiving thoughts, too, and are capable of reflecting on them!)

We find that the ten senses can also be neatly divided into 3 and 7. Like the Sefirot, three of the senses parallel the upper mochin. These are the “invisible” senses of time, space, and self, all of which involve internal body structures. The other seven senses parallel the lower middot and have structures that are on the external surface of the body (eyes, ears, nose, skin, etc.) Also, the first three are those that all human beings share and every living human possesses. Whereas there are people who are completely unable to see or hear, taste, or smell, every human has at least some sense of time, space, and self. Finally, the first three are far more mysterious than the latter seven—the physiology of which we understand down to the molecular level.

The sense of self is, of course, one of the biggest mysteries in science and we are no closer today to unravelling the nature of consciousness. The sense of time, too, is mostly a puzzle. Back in university, I once took a fascinating course on biological timekeeping. I vividly recall the professor, himself a renowned expert in the field, describe how even bacterial cells know what time it is, and that scientists have been able to isolate just three bacterial proteins and put them in a dish—and still the proteins bizarrely work according to a timed rhythm! The sense of proprioception is a little better known, especially regarding the semilunar canals in the inner ear that play a big part in the process. However, those canals are just a tiny piece of a much bigger and more complex operation. (Interestingly, plants have been shown to have a sense of proprioception, too.)

Now, what does all of this have to do with the Ten Plagues?

An Attack on the Senses

There is a principle in Jewish mystical texts that all tens are related. This is because all things ten emanate from the pattern of the Ten Sefirot. It is well-known that the Ten Plagues correspond to the Ten Utterances (in reverse order, so the death of the firstborn corresponds to “Beresheet”, the first spark of Creation; then the plague of darkness corresponds to “Let there be light”, and so on). If all tens are related, how do the Ten Plagues correspond to the ten senses? A careful analysis shows a perfect match:

The first plague of blood was an attack on the sense of taste. Anything that the Egyptians tried to drink took on the bitter, metallic taste of blood. The second plague of frogs was an attack on the sense of smell, as the Torah specifically tells us that the Egyptians “gathered them together in heaps; and the land stank.” (Exodus 8:10) Then came itchy lice, an attack on the sense of touch.

The nature of the fourth plague is subject to some debate. We know Egypt was overrun by animals; the question is what kinds of animals? The oldest translation of the Torah (the Greek Septuagint) has ‘arov as a swarm of flies. Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Itzchaki, 1040-1105) says a mix of all animals, though he specifically notes snakes and scorpions. Sforno (Rabbi Ovadia of Sforno, c. 1475-1550) also says snakes, along with other “creepy crawlers”. Rashbam (Rabbi Shmuel ben Meir, 1085-1185) likes wolves, since ‘arov may allude to the night, erev, when wolves come out and howl. The Ibn Ezra (Rabbi Avraham ben Meir ibn Ezra, 1089-1167) is among multiple commentators who hold that they were great land beasts like “lions, wolves, bears, and leopards”. The latter is generally the most accepted opinion in Jewish tradition. In any case, we can parallel this plague with the sense of hearing. Whether it was the frightening howls of wolves, the roars of lions and leopards, the hisses of waves of snakes, or simply the incessant buzzing of countless flies (or all of the above)—the fourth plague was not good to the ears.

The fifth plague was the death of the Egyptians’ livestock. Considering that much of a person’s wealth in those days was invested in their livestock, the Egyptians could do nothing but watch as their animals dropped dead, ironically through a contagion that was invisible! At the same time, the livestock of the Israelites was perfectly healthy. In disbelief, Pharaoh even sent his people to see for themselves and confirm the impossible phenomenon: “And Pharaoh sent, and, behold, there was not so much as one of the cattle of the Israelites dead.” (Exodus 9:7) The Torah alludes here to the sense of sight.

Then came the sixth plague of agonizing boils, corresponding to the sense of pain. The seventh plague is an obvious nod to the sense of temperature: hail that was both freezing-cold and simultaneously burning hot.

That brings us to this week’s parasha and its final three plagues. It should first be noted that the sense of sight is mentioned with regards to all three—a point we will get back to. However, these three correspond to the higher three Sefirot and the three higher senses. The eighth plague of locust was so thick it was impossible to see, and at the same time filled every inch of the Egyptians’ homes (Exodus 10:5-6). One might imagine how it would cause total disorientation and claustrophobia—an attack on proprioception.

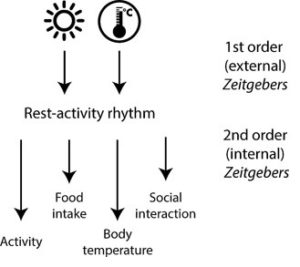

The ninth plague of darkness also made it impossible to see, but wasn’t about sight. In those days there were no wristwatches or wall clocks. The primary means of keeping track of time was by observing the sun and moon, together with the procession of stars. The ninth plague blotted all of that out. There was no way to know the time. From a scientific perspective, our bodies are still able to keep track of time even in total darkness. However, the body does need a regular zeitgeber, some kind of signal to keep its clocks aligned. The main zeitgeber is light, perceived through the eyes. In total darkness, without zeitgebers, a person’s circadian rhythm will slowly drift away from a 24-hour cycle. To make matters worse, the Torah states that the darkness was thick and made it so that the Egyptians couldn’t even move (Exodus 10:23). This made it all the more impossible for the Egyptians to experience any passage of time, while “for all the children of Israel there was light in their dwellings.”

Finally came the death of the firstborn. For the firstborn, this was the obliteration of their very sense of self. For the parent who lost a child, it was an attack on their sense of self, too, as every parent sees their self-reflection in their child, especially their firstborn. In these ways, the Ten Plagues had an additional purpose in striking the Egyptians through each sense of the body.

Senses and Sefirot

On a final note, we can see how the senses and plagues parallel the Sefirot. The first is Chessed, always associated with water, which in Egypt was transformed to blood. Chessed is the Sefirah of love, kindness, and hospitality, so it is fitting that it relates to the sense of taste. Gevurah is the second Sefirah and the sense of smell. Recall that Gevurah is also known as Din, “judgement”, which our Sages associate with the sense of smell. (Perhaps the clearest statement of this is that Mashiach will judge through his sense of smell, see Sanhedrin 97b.)

Touch is the one sense felt literally on every inch of the body, much like the third Sefirah of Tiferet is the only one linked to all the other Sefirot. Netzach and Hod are the Sefirot of prophecy, and neatly parallel hearing and seeing. Prophecy is that ability to peer into the higher worlds—the mochin—which brings us back to the question of why the sense of vision was implicated in those final three plagues that parallel the mochin. Yesod is the Sefirah of sexuality, and corresponds to the sense of pain. That might help explain why the genitals are densely packed with pain receptors, and why injuries to the genitals are among the most painful. (There really is a fine line between pleasure and pain.) That leaves the final Sefirah of Malkhut for temperature.

The mochin are time, space, and self. The feminine Sefirah of Binah relates to the feminine quality of time. (This relates to the general principle that women are exempt from time-bound mitzvot.) Chokhmah is the Sefirah of Creation, and relates to the space of the cosmos. (Interestingly, it corresponds to the creation of light, the photons of which appear to take up space but are seemingly not subject to time!) Lastly, Keter is the Sefirah of will, ratzon, and is the sense of self.

Shabbat Shalom!