This week’s parasha, Terumah, begins outlining the construction of the Mishkan, the mobile Tabernacle. As is well-known, the Mishkan was a microcosm of the universe, and also paralleled the human body and its components. Commenting on the construction materials listed at the start of the parasha, Midrash HaGadol states:

“Gold” is the soul; “silver”, the body; “copper”, the voice; “blue” [tekhelet], the veins; “purple”, the flesh; “red”, the blood; “flax”, the intestines; “goat hair”, the hair; “ram skins dyed red”, the skin of the face; “tachash skins”, the scalp; “shittim wood”, the bones; “oil for lighting”, the eyes; “spices for the anointing oil and for the sweet incense”, the nose, mouth and palate; “shoham stones and gemstones for setting”, the kidneys and the heart.

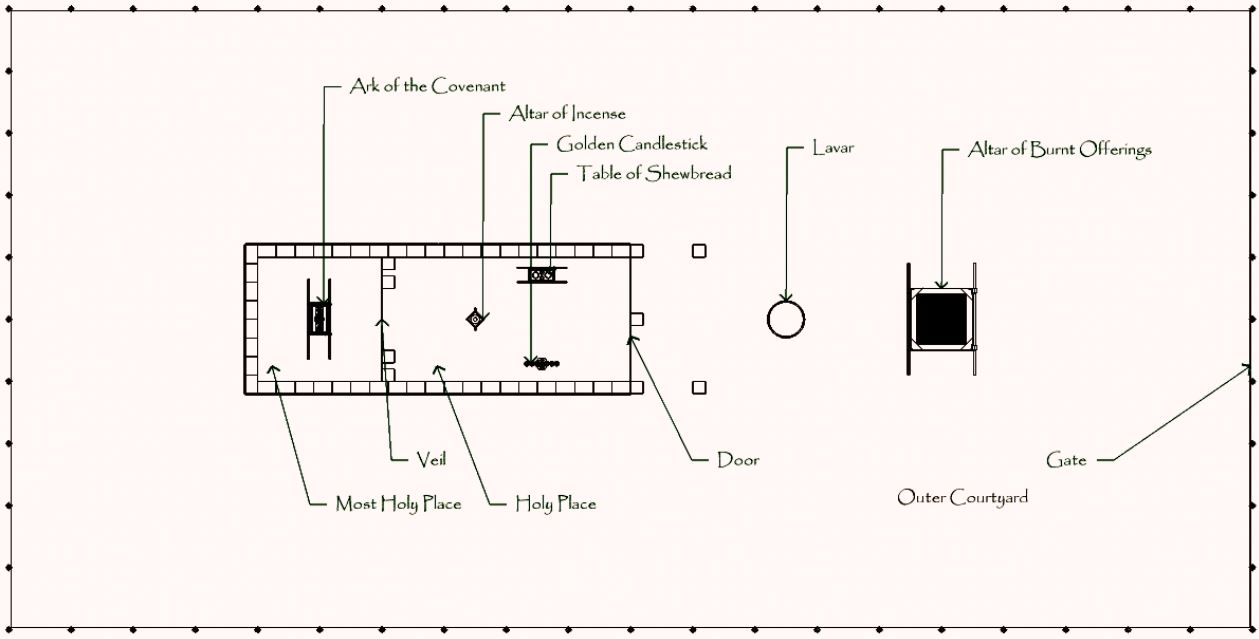

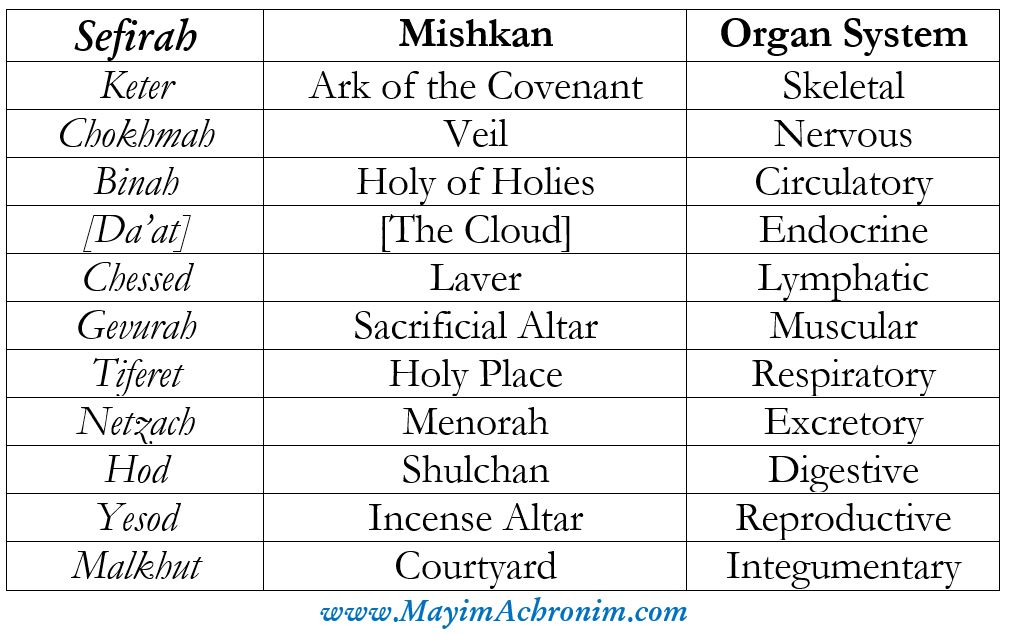

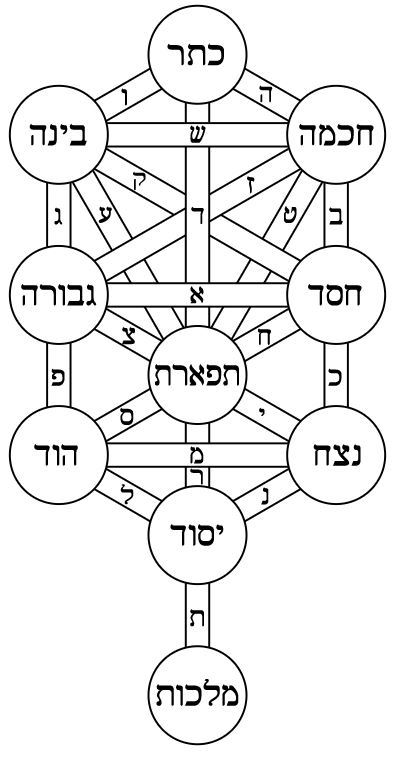

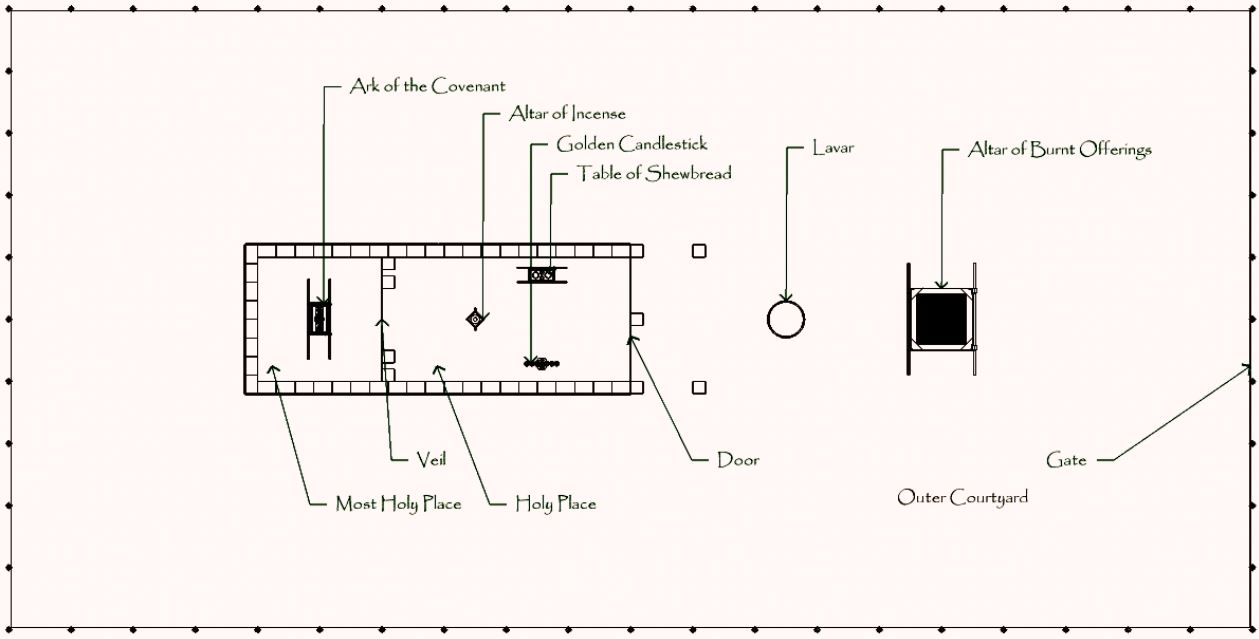

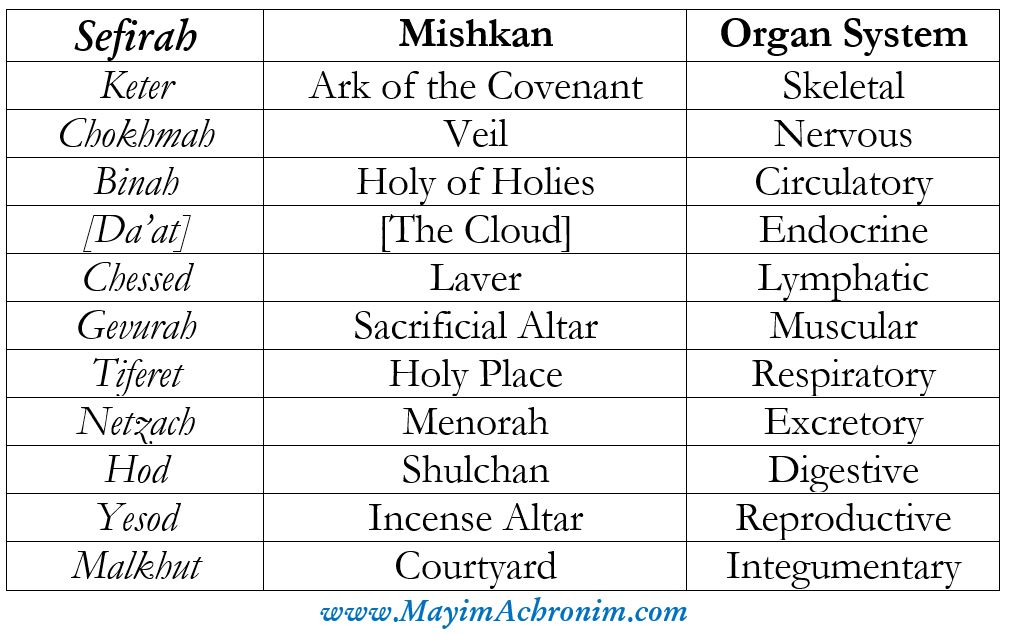

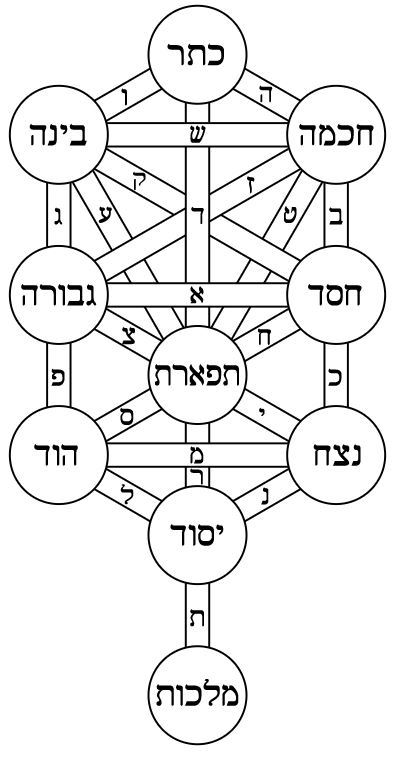

At the same time, we find that there were (not surprisingly) ten major components in the structure of the Mishkan: (1) the courtyard, (2) the laver for washing, (3) the sacrificial altar, (4) the inner “Holy” place, and its three components (5) the Table of Showbread, (6) Menorah, and (7) Incense Altar, followed by (8) the Veil, behind which was (9) the “Holy of Holies”, containing (10) the Ark of the Covenant. As with all tens in the Torah, they correspond to the Ten Sefirot. One way to parallel them to the Sefirot is as follows:

At the same time, we find that there were (not surprisingly) ten major components in the structure of the Mishkan: (1) the courtyard, (2) the laver for washing, (3) the sacrificial altar, (4) the inner “Holy” place, and its three components (5) the Table of Showbread, (6) Menorah, and (7) Incense Altar, followed by (8) the Veil, behind which was (9) the “Holy of Holies”, containing (10) the Ark of the Covenant. As with all tens in the Torah, they correspond to the Ten Sefirot. One way to parallel them to the Sefirot is as follows:

In mystical texts, the trifecta of Binah-Tiferet-Malkhut always represent divine space and Divine Presence. These neatly correspond to the three spaces within the Mishkan: the large and mostly empty courtyard is Malkhut, often described as an “empty” vessel, but also identified most closely with the Shekhinah, the Divine Presence of God as manifest in this lowest of worlds. As soon as a person entered the Mishkan, they would sense the Shekhinah in the courtyard. When one passed the next partition, they entered the Holy space, corresponding to Tiferet. Finally, the innermost sanctum of the Mishkan was the Kodesh Kodashim, the Holy of Holies, the space of which parallels lofty Binah.

Before performing their services, the kohanim first needed to wash in the copper laver. The purifying waters of the laver, of course, represent Chessed, always associated with pure water, kindness and positive energy. Following this, the kohanim could bring offerings on the sacrificial altar to atone for sins, representing the realm of Gevurah and Din, harsh severity and judgement, always associated with fire. Fittingly, this is the place of slaughtering and burning in the Mishkan.

Inside the Holy place, there were three structures. First and foremost was the Menorah, its eternal, ever-burning flames representative of eternal Netzach. The Menorah became a symbol of all of Israel, the oldest symbol of Judaism. It is indicative of our flame that shall never be extinguished, and that no matter how much we are oppressed, we emerge victorious. Opposite the Menorah stood the Shulchan, a table with twelve loaves of bread that remained miraculously fresh. This is symbolic of splendorous Hod. The root of Hod literally means to “acknowledge” and to “thank”, and the Torah commands that it is specifically after eating a bread-meal that we must recite birkat hamazon to thank God and acknowledge all the good that He bestows upon us. (Almost all other berakhot requirements are of rabbinic origin.) Last of the three structures in the Holy is the incense altar, facilitating atonement of the gravest sins, especially those in the sexual realm, associated with Yesod.

Then came the Holy of Holies, corresponding to the highest three Sefirot of the Mochin. The kohen gadol entered past the special Veil, paralleling Chokhmah, and stood before the Ark of the Covenant, representing the very Will of God, Keter. The Ark contained the Ten Commandments, inscribed with a total of 620 letters, the gematria of “Keter” (כתר)! From between the Cherubs above the Ark came the voice of God, revealing His Divine Will. Better yet, mystical texts speak of two higher energies emanating from Keter, called Ta’anug (“Pleasure”) and Emunah (“Faith”). This tie in neatly with the two other items in the Holy of Holies: the jar of manna, representing delicacy and Ta’anug; and the almond-rod of Aaron, representing true Emunah in God and His laws. The hidden Sefirah of Da’at was represented by the “Cloud” of God that descended upon the Tabernacle.

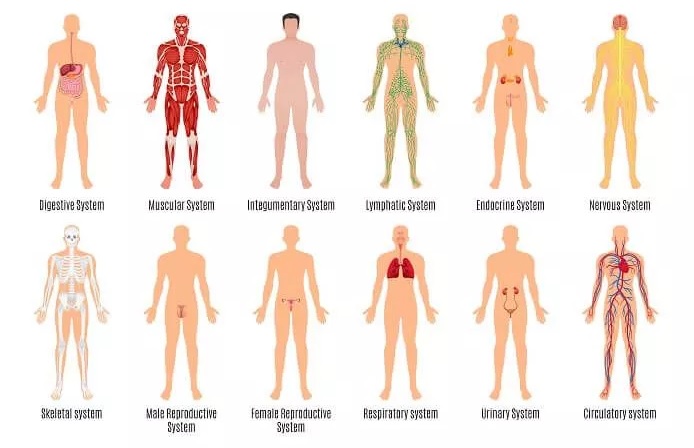

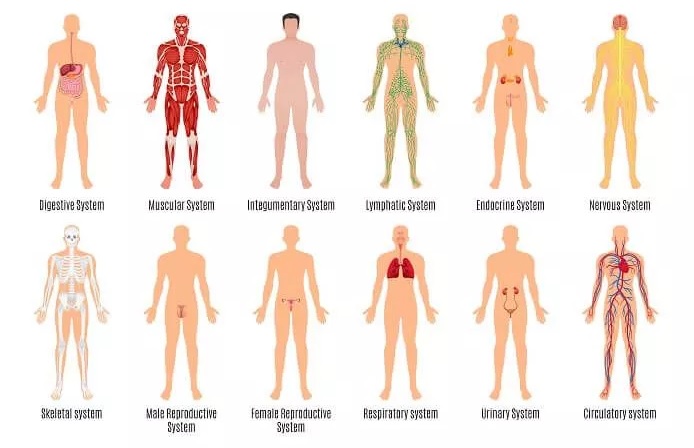

Tying this back to the beginning—the Mishkan as a model of the human body—we find that there are also ten organ systems in the human body that work together to keep us alive and functioning. These organ systems correspond to the Sefirot, too. Keter, the origin from which all the divine energy emerges, is often called the “skull”. It corresponds to the skeletal system that gives structure to the entire body, and without which the body would collapse and have no form or function. Chokhmah is the brain and the nervous system (self-explanatory).

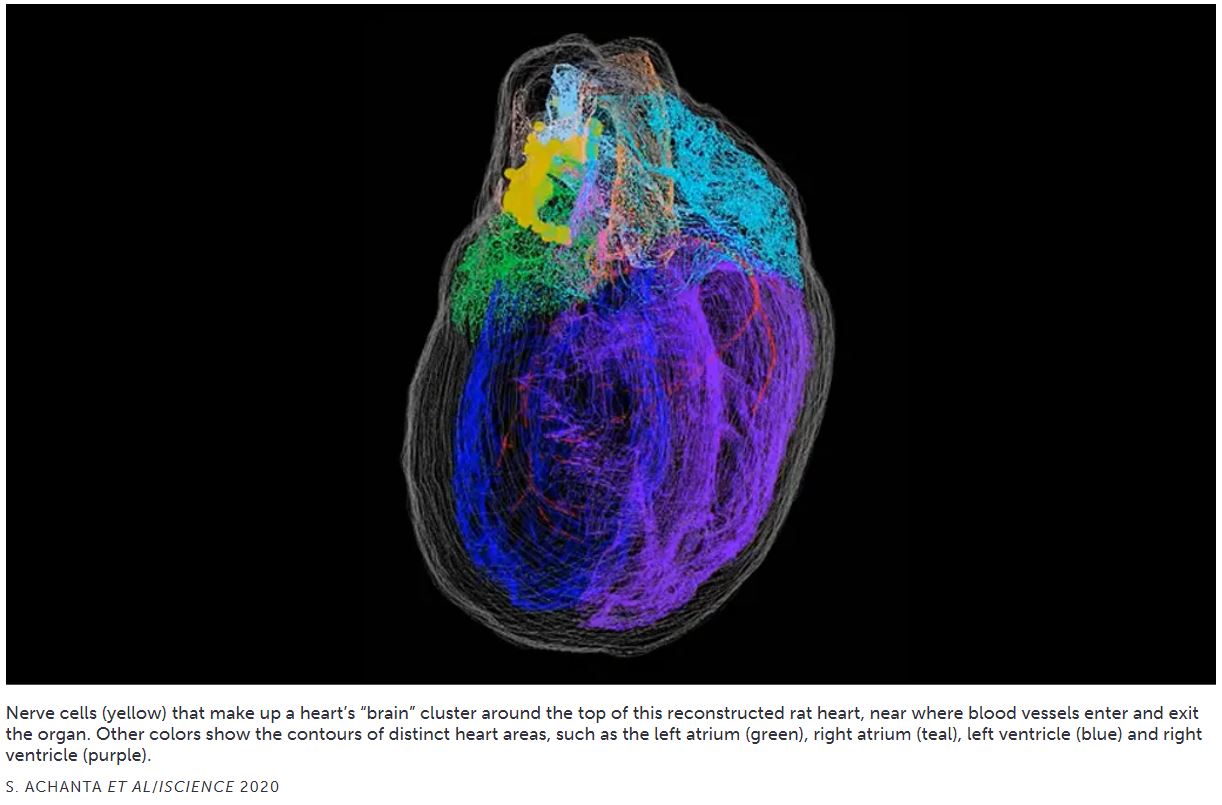

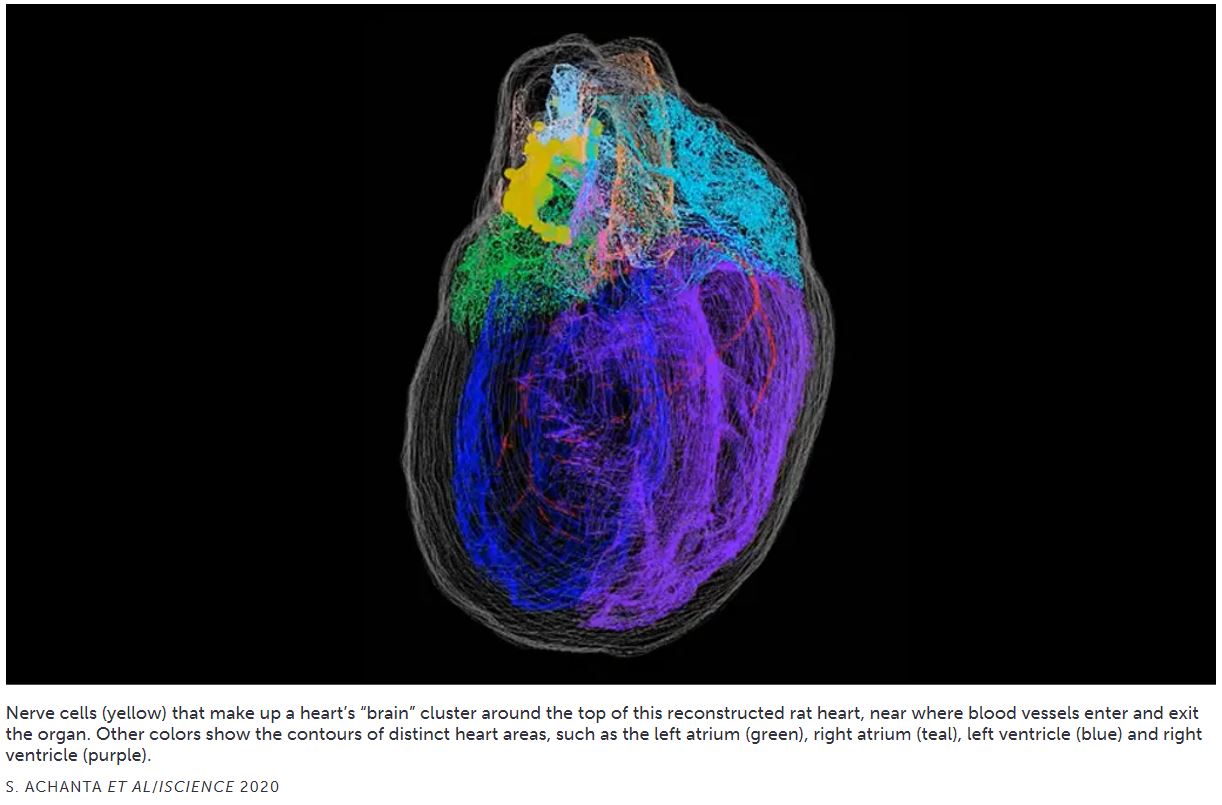

Although Binah is a mental faculty, it is also associated with the heart. Today, scientists know that the heart has a neural network of its own, and may indeed play some role in our emotions and unconscious. The heart has even been called “the little brain” by some researchers. Thus, Binah is a fitting place for the circulatory system. Binah is described as the “mother” that gives birth to the Sefirot below and keeps them nourished. Similarly, the circulatory system delivers vital oxygen and nutrients to every cell of the body.

It is intriguing to note here that Binah is considered a “feminine” Sefirah (being Ima, the “mother”) and we find that women have less issues with heart disease and cardiovascular disorders than men do. Meanwhile, Chokhmah is called the “father” and is a masculine quality, and studies show that women are three times more likely than men to have mental health issues! This gives us further evidence for seeing how the Sefirot manifest themselves in the organ systems of men and women.

The main interface between the nervous system and the circulatory system is the endocrine system, controlling the production and release of hormones. The endocrine system doesn’t actually have any major organs of its own, just a set of glands distributed around the body and overlapping with other systems (like the kidneys of the excretory system and the pancreas of the digestive system). The main control centre of the endocrine system is the brain’s hypothalamus, regulating which hormones get released into the bloodstream. Thus, the endocrine system bridges together the circulatory and the nervous systems—without having any specific organs of its own—nicely paralleling the hidden Da’at which bridges Chokhmah and Binah.

Next in the Sefirot is Chessed, associated with water and with excess and overflow (it is also known as Gedulah, “largesse”). This is the little-known lymphatic system of the body, which transports and regulates excess fluids around the body. The lymphatic system is also important in the development and transport of immune cells (lymphocytes) that protect the body from foreign invaders, another link to the protective energy of Chessed. Moreover, Chessed is typically associated with whiteness, like the milky lymph fluid and the immune system’s white blood cells. In the Mishkan, the laver of Chessed served to wash away germs and impurities (both spiritual and physical), another link to the germ-fighting power of the immune system and lymph nodes.

On the other side of Chessed is strict and fiery red Gevurah, “severity” and “strength”. This parallels the red musculature, the heaviest system in the body, and the one that burns the vast majority of the body’s energy. Like Gevurah, it is the muscles that give us strength. Fittingly, the meat of the sacrificial animal that was consumed in the Mishkan was, of course, muscle. Then comes Tiferet, associated with the element of air, and paralleling the respiratory system. Just as Tiferet plays a central role being in the middle of the Sefirot, and balances them all, the respiratory system is in the middle of the body, bringing in vital oxygen for every cell to stay alive. Tiferet is described as “God’s Throne”, where the Divine Light of Creation is concealed, and to which we all aspire. (The people and Land of Israel are rooted in Tiferet, as explored here.) It is the respiratory system that allows us to elevate our souls Heavenward, to have an “out-of-body experience”, whether through meditative breathwork or through (risky) shortcuts like inhaling various substances.

The dual Sefirot of Netzach and Hod are usually associated with the kidneys, and other filtering organs of the body. They neatly parallel the excretory (urinary) system and the digestive system, respectively. Netzach lies below watery Chessed (of the lymphatic system), and the kidneys filter the fluids in our bloodstream and work in tandem with the lymphatic system. In our prayers, we often speak of God “examining” or “testing” our kidneys (bochen klayot), and some might see in this a metaphor that whenever God gives us tests or tribulations, it is only to “purify” us, just as the kidneys do for the blood. This parallels what was said above about the Menorah as a victorious symbol of our ever-burning flame, despite the difficulties of our history.

Similarly, the digestive system of Hod nicely corresponds to the Shulchan and its loaves of bread in the Mishkan. Recall that Hod is the place of berakhot, through which we “acknowledge” and “thank” God—as mentioned above—and the most frequent way to do this is by reciting blessings on food for the digestive system! Hod lies beneath muscular Gevurah, and there is an important connection here: The digestive system depends on a network of involuntary smooth muscles to move food matter through the system (plus an extra layer of muscle around the stomach to “churn”). Without smooth muscles, digestion would be impossible.

In Kabbalistic texts, fiery Gevurah sometimes represents the entire left pillar of Binah-Gevurah-Hod, all of which is associated with redness and severity; while watery Chessed stands for the entire right pillar of Chokhmah-Chessed-Netzach, associated with whiteness and fluidity. With this in mind, it is especially appropriate that in the array of organ systems, the entire left side relies on red muscles (cardiac muscles of the heart for Binah, skeletal muscles for Gevurah, digestive smooth muscles for Hod); while the entire right side relies on fluids (cerebrospinal fluid for the nervous system of Chokhmah, lymph fluids for Chessed, blood plasma for the kidneys of Netzach).

Lastly, we have the reproductive system for Yesod (obviously), followed by the largest and most superficial integumentary system (of skin, hair, and nails) for lowliest and earthliest Malkhut. Just as skin envelops our bodies, curtains of animal skins enveloped the courtyard of the Mishkan, corresponding to Malkhut. In these ways, we can see how the ten organ systems of the human body neatly parallel the Ten Sefirot, and the ten components of the Mishkan—both a macrocosm of the human body and a microcosm of the universe. To summarize:

At the same time, we find that there were (not surprisingly) ten major components in the structure of the Mishkan: (1) the courtyard, (2) the laver for washing, (3) the sacrificial altar, (4) the inner “Holy” place, and its three components (5) the Table of Showbread, (6) Menorah, and (7) Incense Altar, followed by (8) the Veil, behind which was (9) the “Holy of Holies”, containing (10) the Ark of the Covenant. As with all tens in the Torah, they correspond to the Ten Sefirot. One way to parallel them to the Sefirot is as follows:

At the same time, we find that there were (not surprisingly) ten major components in the structure of the Mishkan: (1) the courtyard, (2) the laver for washing, (3) the sacrificial altar, (4) the inner “Holy” place, and its three components (5) the Table of Showbread, (6) Menorah, and (7) Incense Altar, followed by (8) the Veil, behind which was (9) the “Holy of Holies”, containing (10) the Ark of the Covenant. As with all tens in the Torah, they correspond to the Ten Sefirot. One way to parallel them to the Sefirot is as follows: