This week’s parasha, Korach, has a hidden theme: hair. In fact, the name of the villain himself, Korach (קרח), is spelled exactly the same way as kere’ach, “bald”. As we shall see below, Korach’s rebellion began when he saw himself bald-headed following his initiation ritual as a Levite. Hair comes up again in the famous story of one of Korach’s co-conspirators, a man named On ben Pelet. On is strangely mentioned right at the beginning of the parasha (Numbers 16:1), and never again. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 109b-110a) explains that he was saved thanks to his wife: She told her husband that he had nothing to gain from joining the rebellion; now he was subservient to Moses, and if the rebellion would be successful he would just become subservient to Korach!

On understood, but worried that he had already agreed to join the group. So, his clever wife got him drunk and sleepy, and On passed out in bed. Meanwhile, she went out to the entrance of their tent and “exposed her hair”. When Korach’s collaborators approached, the Talmud says they turned away due to the immodest sight of the woman. By the time On recovered from his drunken stupor, the whole episode was over, and he was spared. This story implies that Jewish women cover their hair, and for a woman to expose her hair publicly is immodest. Yet, nowhere in the Torah is there an explicit command for a Jew to cover their hair at all times (male or female). Hair-covering is not listed among the 613 mitzvot! If it isn’t a Torah mitzvah, where did it come from?

Aside from the mitznefet or migba’at turban mandated for a kohen serving in the Temple, the Written Law doesn’t demand a head covering. The first such discussion appears in the Oral Law, the Mishnah. In Ketubot 7:6, we are given a list of reasons that permit a man to divorce his wife, and groups them into two general categories: dat Moshe and dat Yehudit, or “Mosaic law” and “Jewish law”. There is quite a bit of discussion in rabbinic texts about what exactly is meant by “Mosaic law” and “Jewish law” and how they are different. In short, the former is thought to date all the way back to Moshe himself, while the latter is a Jewish custom of later origin that has become binding. The Mishnah provides examples of what can be grounds for divorce under “Mosaic law”, including a woman feeding her husband untithed produce or being intimate with him while niddah; and examples under “Jewish law”, including “one who goes out with her hair parua, or spins wool in the marketplace, or speaks with every man”. What does it mean for a woman to have her hair parua?

Definitions

The Talmud (Ketubot 72a) discusses the above Mishnah and says that hair being parua is an allusion to the Sotah procedure described in the Torah, where the same mysterious term is used (Numbers 5:18). Recall that the Sotah was a woman suspected by her husband of having had an adulterous affair. She would be brought to the Temple to drink a special mixture that would prove her guilt or innocence. As part of the procedure, the Torah says that the kohen must farah the woman’s head. The assumption in the Talmud is that this word means to “uncover”, and that the woman’s hair would be exposed. Rabbi Ishmael asserts, therefore, that hair covering for women must be d’Oraita, a law directly from the Torah, and not of rabbinic origin. According to Rabbi Ishmael, what is rabbinically forbidden is to even cover the hair partially with something like a basket or hairnet or headband. Other opinions state that covering the hair with such a “basket” is fine. The Terumat haDeshen (Rabbi Israel Isserlin, 1390-1460; I, 242) would later explain that Rabbi Ishmael didn’t mean hair covering is literally d’Oraita (because it clearly isn’t), but that the Torah only alludes to hair covering (רמז דאורייתא יש לה). Whatever the case, it actually isn’t so clear that parua even means “uncovered”!

On the same Talmud in Ketubot, Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Itzchaki, 1040-1105) comments that parua means the kohen should unbraid her hair to make her look unkempt and unattractive. He seems to suggest that this is the same as having one’s hair “uncovered”. This would fit with rabbinic opinions that modest hair doesn’t necessarily mean to cover up every inch, but even to keep the hair tied up in a bun or tightly braided. The Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1138-1204) similarly defines parua as “undone” or “partially covered” describing, for example, a woman that has a handkerchief over her head, but not a full covering. Interestingly, he puts totally “uncovered” (galui) as a dat Moshe, and “partially covered” (parua) as a dat Yehudit (Hilkhot Ishut 24:11-12).

The Rambam goes one step further and rules that the “daughters of Israel should not go with heads uncovered in the marketplace, whether single or married.” (Hilkhot Issurei Biah 21:17) This is right in line with earlier sources, because if an uncovered head is immodest, it makes no difference whether a woman is married or not married in this regard. Logically, all women should cover their heads! The Shulchan Arukh (Rabbi Yosef Karo, 1488-1575) rules the same way in one place (Even haEzer 21:2). Yet, this has not caught on as the accepted practice, and it is only married women that are expected to cover their hair.

The Malbim (Rabbi Meir Leibush ben Yehiel Michel Wisser, 1809-1879) explains the term parua most precisely, pointing out that the exact same word is used by the Torah in reference to the nazir, who was not allowed to cut his hair. The Torah says the nazir must gadel pera se’ar rosho, which is translated that he must grow out his hair long and unkempt, without neat haircuts (Numbers 6:5). Pera does not mean “uncovered”, because a nazir is obviously not forbidden from wearing a kippah or a tallit over his head!

The Malbim further points out that the same word is used in Ezekiel 44:20, where the prophet instructs that kohanim must maintain proper appearance when serving Hashem, and cannot have their hair fera because they must “surely keep their hair trimmed”. Thus, the meaning of the term is quite clear and unambiguous: pera (פרע) means unkempt, untrimmed, and messy; it does not mean uncovered! The same root means to “interrupt” or “disturb”. (And it may very well be related to per’e, פרא, with an aleph, which means “wild” and “unruly”, as Ishmael is described in the Torah.)

With this in mind, we can go back to our Mishnah: it says a woman cannot go out with her hair parua, unkempt and untidy, messy like a Sotah. A Jewish woman (and a man, for that matter) must maintain proper and respectable appearance, as one would expect of a representative of God. A Jewish woman must look like a daughter of Hashem, not a wild and untidy person. This is closely related to another discussion of our Sages elsewhere:

In Shabbat 6:5, the Sages address the prohibition of carrying outside on Shabbat and state that a woman can go out with a wig or hairnet or even just hair extensions (made from her own hair, or her friend’s hair, or the hair of an animal). The Talmud (Shabbat 64b) begins its exploration of this Mishnah by defining various terms before moving into a discussion of a woman’s appearance. The general rule is that women must look dignified and presentable, and the Sages cannot impose stringencies that will take away from this. When some authorities tried to forbid a niddah from putting on makeup, Rabbi Akiva stopped them because it could have resulted in women becoming unappealing to their own husbands, and divorce rates would skyrocket!

To summarize where we are so far: covering hair is not explicitly from the Torah, and not a mitzvah listed among the 613. The Torah and Mishnah (meaning the original Written and Oral Law) only prohibit a woman from going out with her hair unkempt, untidy, and unruly (parua). It is only from the Talmud onwards that there is an assumption that women must cover their hair entirely, but even there we find voices that say covering partially with a basket, net, wig, or cap is sufficient. The Rambam rules that hair must be covered completely, and even lists fully-uncovered hair under the more stringent category of dat Moshe.

One last element worth noting is that the same Talmud in Ketubot (72b) differentiates between various public and private areas. Going out to the “marketplace” (shuk) uncovered is forbidden, but being uncovered in the “courtyard” (chatzer) is not. Meaning, in the immediate area around one’s house—the common space that might be shared by close neighbours and families; that is not a public thoroughfare for strangers—a woman could be uncovered. Otherwise, the Talmud says, “not a single daughter of Avraham would remain married to her husband”! The Sages were realistic and did not want to impose overly difficult stringencies.

The big question still unanswered is why does a woman need to cover her hair at all? The first and most common answer is, of course, modesty.

Modesty

In Scotland, it is still customary to wear a kilt to a wedding. Jews in Scotland wear kilts, too. (Credit: Brian at XMarksTheScot.com)

Under the overall umbrella of a Jew always appearing dignified and graceful in public is to be modest. Definitions of modesty change over time, and wider society often dictates what is modest and what isn’t modest, what is appropriate and what isn’t appropriate. For example, a Jewish man is forbidden from wearing a skirt—but not in Scotland! One might find men wearing kilts on special occasions in Scotland, even at a Jewish wedding. Local custom does impact halakhah in this regard, and the Rambam (in Hilkhot Avodat Kokhavim 12:10) writes, for instance:

A woman should not adorn herself as a man does. She may not place a turban or a hat on her head or wear armor or the like. She may not cut [the hair of] her head as men do. A man should not adorn himself as a woman does. He should not wear coloured garments or golden bracelets in a place where such garments and such bracelets are worn only by women. Everything follows local custom.

In Jewish law, what constitutes “modesty” does depend on local custom and wider societal norms. Regarding hair covering, one might apply the same logic. Back in the day, when essentially all women in all parts of society were expected to cover their hair in public, this was a basic standard of modesty. Today, when the vast majority of women no longer cover their hair in public, is it still “immodest”?

The Ben Ish Chai (Rabbi Yosef Chaim of Baghdad, 1832-1909) wrote a halakhic work on modesty for women, in Arabic, called Kanun al-Nisa. He noted (in chapter 17) the argument that in Europe hair is no longer ervah (“nakedness”), sexually arousing, since women there no longer covered their hair anyway. Presumably, though, it was still ervah in his native Iraq, where many women did continue to cover their hair. Several decades later, Rav Yosef Messas of Morocco (1892-1974) ruled that uncovered hair is permissible considering the wider societal changes. He explained that he ruled this way regrettably because, again, the vast majority of Jewish women were already going uncovered anyway, and he saw no way of “returning the matter to the way it once was”. Based on the wider social changes, he went so far as to say that “the prohibition has been fundamentally uprooted and has become permissible.”

Now, what actually is ervah? The Talmud discusses the term in Berakhot 24a, in the context of a man reciting Shema. The Sages there say that a man cannot recite Shema if his wife is exposed before him. Some go further and say one shouldn’t do so even if it’s just a handbreadth of his wife’s skin that’s exposed. A few more individual opinions are given: Rav Hisda says a woman’s thigh is ervah, Shmuel says a woman’s voice, and Rav Sheshet says a woman’s hair. Again, all of this is only in the context of a man praying in the same vicinity as his wife. If he can see her skin or her thigh or her hair, or hear her voice, it will surely distract him from prayer. Over the centuries, this understanding of ervah spread to all aspects of life more broadly, not just during prayer. Women’s hair became “immodest”.

This begs the question: why have wigs become acceptable in many branches of Orthodox Judaism? If hair is inherently immodest, where is the logic in covering hair with someone else’s hair? If covering hair is meant to attract less attention, what is the logic in exquisite wigs that can cost thousands of dollars and clearly enhance a woman’s beauty? Some will argue that it isn’t about suppressing the beauty or attractiveness—ie. it’s not really about modesty or discreteness—rather, hair covering is something much more spiritual and energetic.

Curses and Demons

One often hears religious women say they cover their hair to contain the “Shekhinah” emanating from there, or some other holy energy, or to embody the “feminine” Shekhinah in some other ethereal way. Based on this, one could argue that the method of covering hair is irrelevant, whether scarf or hat or wig. The point is to cover it up so that the energy is not lost. This is an interesting possibility, but one not sourced in anything ancient or particularly authentic. In fact, the reality appears to be exactly opposite!

The Zohar says that hair stems from the “Left Side” or “Other Side”, the Sitra Achra, the realm of evil. This is why hair is se’ar (שער), sharing a root with se’ir (שעיר), “demon”. Esau was very hairy because he was connected to that side (III, 64a). The Levites, too, stem from that side, and therefore had to be entirely shaved top-to-bottom in their initiation ritual to remove all the negative energy (III, 48b). The Zohar says that this is precisely what precipitated the whole Korach incident! “Korach was the greatest of the Levites”, the Zohar notes, and when he had to be entirely shaved and saw himself bald, while his cousin Aaron was beautifully adorned in priestly garments, “he felt degraded and jealous”.

The Arizal later added that hair on the head in particular represents harsh Din, “judgement” (see Sha’ar haGilgulim, Ch. 34, and Sha’ar haMitzvot on Kedoshim and Nasso). This is why, the Arizal says, it is actually good for a man to go bald! Rabbi Akiva was bald-headed, and was nicknamed kere’ach, “the bald one” (which again circles back to this week’s parasha, Korach). A man can trim his head hair short and neat, or even entirely shaved off, to keep the Din and negative energy subdued. (It should be noted that white hair is not Din, but rachamim gemurim, “complete mercy”, and shouldn’t be shaved!)

Since women are expected to have long, flowing hair, this apparently becomes a source of tremendous negative energy and Din exuding outwards. The Zohar (III, 79a) even suggests that a woman’s hair (and nails) grow long because of powerfully impure forces stemming from the Primordial Serpent. Thus, the idea is to cover it all up and contain it. This might explain the custom among some ultra-Orthodox women to actually shave their heads entirely and wear a wig. Indeed, it is the Zohar (III, 125b) that is first to describe head covering in extremely harsh language:

A curse shall come upon the man who allows his wife’s hair to be seen. This is one of the matters of modesty in the home. If a woman reveals her hair, she causes poverty in her home, and makes her children disrespected in the generation, and causes “another thing” to rest in the home. This is the hair that she reveals, and if it is so within the home, how much more so outside in the marketplace… Therefore, a woman should make sure that even the beams of her house do not see her hair, and all the more so outside!

The Zohar here is echoing an earlier Talmudic story about Kimchit, a woman who merited to have seven sons all become kohen gadol. When asked what was her merit, she replied that “the beams of my house never saw the braids of my hair.” (Yoma 47a) The novel element added by the Zohar is that hair is inherently negative and impure, connected to the Primordial Serpent and the “Original Sin” of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. In short, it’s not about retaining any kind of positive energy or “Shekhinah” divinity as some today claim; on the contrary, it is about negative energy and impurity. If that’s the case, why is it that a woman’s hair is described so negatively? Here, we can finally get to the bottom of the issue. What follows is the real reason that women are required to cover their hair, and it may come as a shock:

The Torah tells us that after the consumption of the Forbidden Fruit, the four parties involved were all cursed by God. Although the Torah’s language is brief, the Sages derive that a total of 39 curses were pronounced: ten upon Adam, ten upon Eve, ten upon the Serpent, and nine upon the Earth itself (see Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer, Ch. 14). These 39 curses correspond to many things, including the 39 lashes one might get for certain transgressions (which, mystically, rectifies the First Transgression of Adam and Eve, since all transgressions ultimately stem from there). It corresponds to the 39 prohibited melakhot of Shabbat, too. On a deeper level, Shabbat is meant to reverse those curses of Eden. On Shabbat, we get a taste of what it would be like if those curses never entered the world, including the curse of hard labour. (For lots more on this, see ‘Reversing the Curses of Eden’ in Volume Two of Garments of Light.)

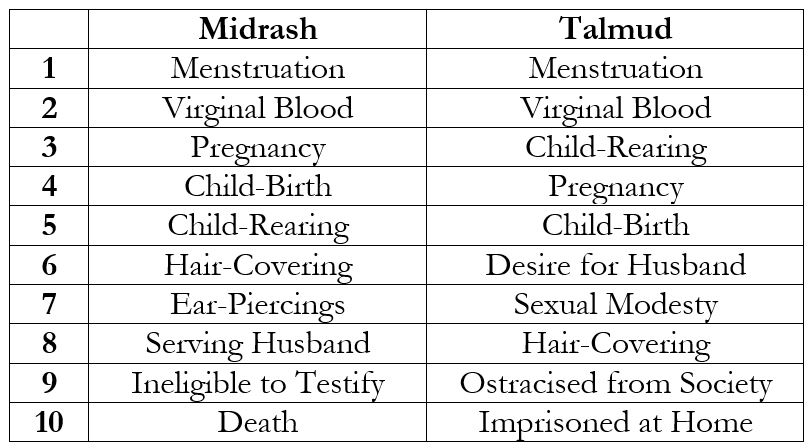

The Midrash (ibid.) delineates what exactly the curses were, and here we want to focus on the curses of Eve:

He gave the woman nine curses and death: [1] the afflictions arising from menstruation, and [2] the tokens of virginity; [3] the affliction of conception in the womb; and [4] the affliction of child-birth; and [5] the affliction of bringing up children; and [6] her head is covered like a mourner… and [7] her ear is pierced like [the ears of] perpetual slaves; and [8] like a hand-maid she waits upon her husband; and [9] she is not believed in [court] testimony; and after all these, [10] death.

The Talmud (Eruvin 100b) similar lists the curses as:

“To the woman He said: I will greatly multiply” – these are the two drops of blood: [1] the blood of menstruation and [2] the blood of virginity. “Your pain” – this is [3] the pain of raising children. “And your travail” – this is [4] the pain of pregnancy. [5] “In sorrow you shall bring forth children” – in accordance with its plain meaning. “And yet your desire shall be to your husband” teaches that [6] the woman desires her husband when he sets out on the road, “and he shall rule over you” teaches that [7] the woman demands her husband in her heart [but is too shy to voice her desire], but the man demands his wife verbally. Rav Itzchak bar Avdimi says: This is a good trait in women! …Now these are only seven. When Rav Dimi came from Israel to Babylonia, he said that the other curses are: [8] A woman is wrapped up like a mourner [she must cover her head]; and [9] she is ostracized from all people, and [10] she is incarcerated within a prison [as she spends all her time in the house].

Comparing the two lists, we have:

We find that the first five are identical, just in a different order. The only other item that is the same in both lists is hair covering! Apparently, for a woman to cover her hair is a bona fide curse. And many righteous Jewish women who do cover their hair would agree with this statement, often reporting how uncomfortable and unpleasant it is to always have to be “wrapped up like a mourner”.

Of course, these curses were a result of a mistake, and were always meant to be temporary. When Mashiach comes, we will return to the original idyllic world that Hashem created. And in that world, there are no curses at all, and therefore women will not cover their hair, just as Eve originally did not in the Garden of Eden. In fact, we are clearly already transitioning into this world now. Take a look at that list of curses again. Menstruation can now be controlled or stopped entirely with medications and intrauterine devices (and many religious Jewish women today choose not to have periods at all). The pains and aches of pregnancy can be significantly reduced and alleviated through all the advances in medicine, technology, psychology, midwifery, and so on. The pain of childbirth can be greatly mitigated with epidural anaesthetics and other means. Women are no longer “imprisoned at home” and are free to participate in all aspects of society. Women are no longer simply “servants” of men, or second-class citizens. Religious Jewish women are studying, working, starting businesses, serving in government, running large organizations, and so on. The reality is that most of the curses of Eden have already been lifted. Hair-covering remains, but as surprising as it might be to hear, it’s only a matter of time before it’s gone, too.

The reality is that hair doesn’t have to exude negative energy; it can exude positive energy, too. After all, the same se’ar root is also the root of sha’ar (spelled the same way), “gate”, and it is women in particular that are associated with the “motherly” Sefirah of Binah, and its 50 Gates of Understanding (Nun Sha’arei Binah). As the Geulah approaches, this is precisely what is supposed to happen: the forces of Gevurah and Din will give way to the forces of Chessed, and to the forces of Binah which sits above Gevurah on the tree of Sefirot. Recall that the 50th gate is associated with the Yovel, the “Jubilee”, and the “proclamation of freedom throughout the land” (Leviticus 25:10), with all of God’s people returning to their ancestral homes, as all Israel will when Mashiach comes.

To summarize: for a woman to cover her hair is not one of the 613 mitzvot, and it is one of the 10 curses of Eve. There is no doubt that the vast majority of halakhic sources clearly make it mandatory. That said, there is a debate to be had regarding changing societal standards of modesty and appearance, and whether hair should still be considered ervah. Lastly, there is no doubt that once the Geulah comes and all curses are lifted, hair covering will not be mandatory anymore. Amazingly, the Talmud actually states (Sotah 12a) that righteous women are spared the curses of Eve, and are not subject to them even now!

A young Rav Ovadia Yosef, with his Margalit and children Adina and Yakov, while serving as rabbi in Egypt.

To conclude, many have asked for my personal opinion on this matter, so here it is:

I certainly think it is praiseworthy for a woman to cover her hair with a headdress of some sort, because it is indeed more modest, can serve as a marital status symbol, as an indicator of being aware of God above, and because it does encourage others to focus on inner beauty instead of external appearance. Most of this would not apply to a woman wearing a nice wig, though, which I believe is nothing more than a loophole that accomplishes essentially nothing.

I do understand a woman who does not cover her hair because she feels that it is a curse (which it is, as per Midrash and Talmud), or sees it as a mark of oppression and subservience, or a punishment to always be “wrapped up like a mourner”. I also understand one who does not want to cover her hair because she feels it diminishes her appearance or makes her uncomfortable for whatever reason. There is room to be lenient in light of the wider change in society where exposed hair is no longer considered immodest or sexually arousing. And there have been poskim (like Rav Yosef Messas) that permitted it.

I think there is a middle-ground in all of this, where a woman can at least partially cover her hair with some sort of headdress—whether a hat or scarf or even a headband—that indicates she recognizes Hashem above (as a kippah does), that enhances modesty, or that might serve as an indicator of marital status.

In any case, I firmly believe we are in Ikvot haMashiach, and the return to Eden is fast-approaching. We’ve already seen nearly all the curses disappear, and it is only a matter of time before the remaining few curses are lifted, too, and righteous women (and men) will be free once more to choose as they wish without shame, prejudice, or punishment.

Shabbat Shalom and Chodesh Tov!

To continue the conversation, some vital questions to discuss at your Shabbat table or with your family, friends, and rabbis:

1) Is hair still ervah or immodest when the vast majority of women in wider society do not cover their hair, and we are all exposed to hair all the time?

2) If hair is immodest or seductive or exudes negative energy, why do we only require married women to cover up? Shouldn’t all ladies do so from bat mizvah on? Indeed, the Rambam and Shulchan Arukh codify the law as such, so why does halakhah today not follow?

3) If covering hair is meant to be about drawing less attention in public and preserving a women’s best only for her husband, why has it become normal for women to wear very attractive wigs (often nicer than their own hair, sometimes indistinguishable)? What is the logic of covering one’s hair with someone else’s hair?

4) How do we understand the progression of halakhah becoming increasingly more stringent over the centuries? The Talmud permits a woman to be uncovered in the courtyard around her home, but not in the marketplace, and some permit partial coverings even in the marketplace. Post-Zohar, women are seemingly not permitted to be uncovered at all, not even at home! By the time you get to recent centuries, you have some women shaving their heads entirely under their head-coverings, or wearing two head-coverings, such as a wig and a hat on top. How did we go from being okay with uncovered hair at home and outside around the home, to having multiple coverings even inside the home? (Today, there’s even a tiny minority of Ultra-Orthodox communities that have adopted Muslim-style burkas! They call them frumkas.) Where does one draw a line?

5) Most importantly, if the actual reason for covering hair is a curse going back to Eden—as our Sages clearly stated—and we are now in Ikvot haMashiach having already seen most of the curses lifted, why do we still insist on maintaining this particular curse of hair-covering? Does anyone argue that women should remain second-class citizens because Mashiach hasn’t come yet? Does anyone argue that epidurals should be forbidden because woman must remain cursed and suffer until Geulah? Probably not, so where’s the logic in insisting that women must continue covering their hair, especially in light of the wider changes regarding what constitutes modesty and ervah?

For further reading and an in-depth, multi-part halakhic analysis, see here.

See also the class on “Feminism and the Curses of Eve”.

Pingback: Ten Rectifications for Judaism | Mayim Achronim