The Haftarah of this week’s parasha, Vayishlach, ends with these words (Ovadiah 1:20-21):

And this exiled host of the children of Israel who are among the Canaanites as far as Tzarfat, and the exile of Jerusalem which is in Sepharad shall inherit the cities of the Negev. And saviours shall ascend Mount Zion to judge the mountain of Esau, and the kingdom shall be the Lord’s.

This verse happens to be the origin of the term “Sephardic Jew”. By the 13th century, Jews on the European continent were divided into four groups: the Ashkenazis were those in the Germanic lands, the Sephardis in the Iberian Peninsula, the Tzarfatis in France, and the “Canaanites” in Bohemia and Moravia (roughly what is today the Czech Republic). Those last two groups have been forgotten in our days. Yet, Jewish texts from that era make it clear that Tzarfati Jews were once a distinct category, as were the Canaani Jews (which in some texts appear to refer to those Jews living in all Slavic lands). These divisions were based on the verse above from this week’s Haftarah, which describes the Jewish people exiled as far as Tzarfat and Sepharad, and dwelling among distant Canaanites. (It is important to remember that in the Tanakh the word “Canaan” does not always refer to the ethnic Canaanites, but can also mean “merchant” more generally.)

Today, the Jewish world is often divided more simply among Ashkenazi and Sephardi lines. Having discussed the origins of Ashkenazi Jews in the past, we now turn to the Sephardis. However, I don’t want to focus here on the history of Sephardic Jewry. (In short: Jews arrived in Iberia at least as far back as Roman times, and began to migrate on mass after the Muslim conquest in 711.) The big question is: what makes a person “Sephardi” today, considering that Spain expelled all of its Jews in 1492—and didn’t officially rescind that decree until 1968!

In other words, few Sephardis today are actually Spanish or Portuguese, and haven’t had any real connection to Iberia for centuries. There is also the question of who counts as a Sephardi? Are the vast numbers of Jews from the great communities of the Middle East and Central Asia (including Syrians, Iraqis, Bukharians, and Yemenites) to be considered Sephardi? Are they a distinct group of “Mizrachi” Jews? What exactly makes someone Sephardi?

Ethnicity or Hashkafa?

A map of my ancestry results from a 23andMe genetic test. Blue regions represent the highest percentages of genetic origins; green represent low percentages.

One thing that is generally not appreciated today is how much migration and exchange there was between cultures in olden times. Communities were not as isolated as we tend to think. Jews especially were prone to migrate from one place to another. I’m fully Bukharian, but also know that an ancestor going back 6 generations from my father’s side came to Bukhara from Iran, while an ancestor from my mother’s side going back 7 generations came to Bukhara from Morocco. Even though Bukhara is firmly in Central Asia, my DNA test showed that less than 2% of my DNA is actually Central Asian in origin. Another 2% is North African, while over 90% is Middle Eastern. Only 0.3% is Spanish (and 0.1% Ashkenazi!) Most “Sephardis” who take a test like this will probably get a similar result. In that case, what makes us “Sephardi”?

The question was once posed to Rav Ovadia Yosef, the greatest Sephardic authority of recent times. He himself was born in Iraq, and would be more properly defined as a “Mizrachi” Jew. Nonetheless, his answer was that we are Sephardi because we follow the halakha and opinions of the great Spanish Sages, namely the Rambam and Rav Yosef Karo (both of whom were born in Spain proper). And so, what makes a person “Sephardi” is not so much their ethnicity or their genetics, but their style of Jewish thought and practice.

More than anything else, what characterizes Sephardic Judaism is its openness—to art, philosophy, science, and mysticism. The first Hebrew grammarians and poets were Sephardic, including the Radak (Rabbi David Kimhi, 1160-1235) and Shlomo ibn Gabirol (aka. Avicebron, c. 1021-1070). The Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1135-1204) was a world-renowned physician and philosopher, while Avraham ibn Ezra (c. 1089-1167) was a great mathematician and astronomer (for whom scientists have named a crater on the moon). The astronomical tables of Rabbi Avraham Zacuto (c. 1452-1515) were so important that few sailors traveled without them, and they once saved the life of Christopher Columbus!

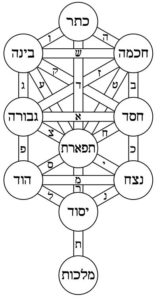

The Sephardis sought to re-establish an independent Jewish state at least as far back as Donna Gracia (1510-1569) and her nephew Joseph Nasi (1524-1579), and the Zionist movement would have nothing without the foundational work of Rabbis Yehuda Bibas and Yehuda Alkali, as well as the great Sir Moses Montefiore. Of course, it is needless to say that almost all of Kabbalah and Jewish mysticism is the work of the Sephardic Sages: the Raavad (Rabbi Avraham ben David, 1125-1198, who originated the now-popular diagram of the Ten Sefirot) and Avraham Abulafia, followed by the circle of Rabbi Moshe de Leon (c. 1240-1305) who revealed the Zohar to the world.

After the Spanish Expulsion, it was Rabbi Yosef Saragossi (1460-1507) who established Tzfat as the world capital of Jewish mysticism. The town became the home of the Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, 1522-1570) and Rav Yosef Karo (1488-1575), who produced the Shulchan Arukh, still the primary code of Jewish law. And perhaps the best example of what it means to be Sephardi is the Arizal, Rabbi Isaac Luria (1534-1572). Despite having an Ashkenazi father, and being referred to as HaAshkenazi, he lived his life as a “Sephardi”, praying in the Sephardi style and generally following Sephardi rites. (With some exceptions; for example, he would pray in the Ashkenazi style during the High Holidays).

In characteristic Sephardi fashion, the Arizal taught that a Jew must learn Torah on all four levels of Pardes, the “orchard” (the root of the word “paradise”), standing for: pshat, the simple reading; remez, reading between the lines; drash, the allegorical; and sod, the secret and mystical. Accordingly, he instructed that one should divide their study into quarters: a quarter for the Written Torah (including Nevi’im and Ketuvim), a quarter for Mishnah (and Midrash), a quarter for Talmud, and a quarter for Kabbalah. These correspond to the four levels of Pardes (as well as to the Ten Sefirot and the four mystical universes, as follows: Tanakh in Asiyah, Mishnah and Midrash in Yetzirah, Talmud in Beriah, and Kabbalah in Atzilut). The Arizal went so far as to say that a Jew who does not learn Torah on all four levels has not fulfilled the mitzvah of Torah study! And this is precisely the Sephardic approach. It has been beautifully pointed out that the word Sephard (ספרד) has the same letters as Pardes (פרדס). Better yet, the final letter samekh comes first, signifying that the Sephardi approach is to prioritize the spiritual, esoteric, and mystical. It comes right back to the idea of the Sephardi openness to art, philosophy, and science—all of which are deeply intertwined with mysticism and Kabbalah.

And it is because of this that Sephardic Judaism has always thrived. There was no “Reform” movement in the Sephardic world, no need for “Maskilim”, and no mass secularization like that experienced in the Ashkenazi world. To this day, while the majority of the world’s Ashkenazis are totally secular (if not anti-religious), the majority of Sephardis are traditional, and at the very least have tremendous respect for the Torah. All of this was well-known among the early Hasidic Jews, who sought to inject a little Sephardi-ness into the Ashkenazi world. (The Hasidic siddur is still referred to as “Sephard”! Having said that, it is one of the great ironies of Jewish history that today’s Hasidim—possibly with the exception of Chabad and Breslov—are the exact opposite of what the early Hasidim stood for.)

So, what does it mean to be Sephardi? Like Rav Ovadia said, it means to emulate the great Sephardi Sages of the past. It means being like the Rambam—a rationalist who can balance his study of Torah and Talmud with science and philosophy. It means being like Rav Yosef Karo—a punctilious halakhic Jew who is simultaneously a mystic. It means one can be a renowned poet like Rabbi Yehuda haLevi (c. 1075-1141, who is today more famous for his Kuzari), and a playwright like the Ramchal (Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto, whose works are now standard yeshiva reading), or even a painter and physicist like Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan (1934-1983). It means being immersed in the world of Torah without separating from the world at large. It means being a proud, fearless (but God-fearing) Jew.

Sadly, in recent decades Sephardiness has been disappearing at precisely the time it is needed most. Now is the time to show the world (including the Jewish world) what “Sephardi” really means. And this has nothing to do with ethnicity. The supposed ethnic labels of “Ashkenazi”, “Sephardi”, and so on mean nothing anyway. We are all just Jews, and anyone can be “Sephardi” in their outlook. Rav Ovadia Yosef’s life mission was, in his words, lehachzir atarah leyoshnah, “to restore the crown to its former glory”. He was referring most directly to Sephardic Judaism, but I think he really meant all of Judaism.

Rav Ovadia may have been Iraqi, and the Arizal may have been Ashkenazi, and I may be Bukharian, but we’re all still Sephardi. How about you?

Pingback: The Origins of Ashkenazi Jews | Mayim Achronim

Pingback: Define: Ashkenormativity – Virtually Jewish

Pingback: Mayim Achronim