On Chanukah we commemorate the victory of the Maccabees over the Seleucid Greek oppressors. The leader of the revolt was an elder kohen named Matityahu ben Yochanan. The second chapter of the Book of Maccabees describes how the revolt broke out: the Greek officers came to Modi’in requesting a sacrifice be made in honour of the wicked king. As Matityahu was the most illustrious elder in the city, he was approached specifically and told that he would be rewarded greatly if he brought the offering. Matityahu replied:

I and my sons and my kindred will keep to the covenant of our ancestors. Heaven forbid that we should forsake the law and the commandments! We will not obey the words of the king by departing from our religion in the slightest degree. (2:20-22)

Another Jew then came up to offer the sacrifices, and Matityahu “sprang forward and killed him upon the altar. At the same time, he also killed the messenger of the king who was forcing them to sacrifice, and he tore down the altar.” (v. 24-25) The Book of Maccabees compares Matityahu to Pinchas, who had struck down the wicked Zimri back in the generation of Moses.

We are then told that Matityahu “and his sons fled to the mountains, leaving behind in the city all their possessions.” (v. 28) They launched a full-scale revolt against the Seleucids, and “Then they were joined by a group of Hasidim, mighty warriors of Israel, all of them devoted to the law.” (v. 42) Originally, the warriors were not called “Maccabees”—that was only the nickname of Yehuda—but rather Hasidim, the “pious ones”. History’s first Hasidim were mighty warriors!

Matityahu himself passed away soon after and, following an impassioned final speech, left Yehuda in charge of the military, while placing Shimon in charge of making decisions (v. 65-66). Shimon would go on to be the only son to survive, and became the leader of Israel when peace was achieved. Though he did not take the title of “king”, he established the Hasmonean dynasty. (We previously explored his true identity here.)

In the Second Book of Maccabees (8:22-23), we learn how Yehuda divided up his forces:

He appointed his brothers also, Shimon and Yosef [Yochanan] and Yonatan, each to command a division, putting fifteen hundred men under each. Besides, he appointed Elazar to read aloud from the Holy Book, and gave the watchword, “God’s help!” Then, leading the first division himself, [Yehuda] joined battle against Nicanor.

‘Death of Eleazar’ by Gustav Doré

It’s amazing to read that Yehuda made sure to leave his brother Elazar with a group of people to learn Torah and pray. Later, Elazar himself would join the fray, and tragically died by being trampled under a war elephant, in an attempt to strike down a Greek general. Strangely, in the passage above one of the brothers is called “Yosef”, when we know that he is actually called “Yochanan”. Is this a simple error? Did Yochanan have two names or is, perhaps, the text alluding to a mystical secret about the spiritual nature of the five sons of Matityahu? I believe the latter is a very real possibility, for we find the story of Matityahu and his five sons seemingly repeated in a different group of people, some three hundred years later.

Rabbi Akiva’s Rebellion

In the 2nd century CE, the Seleucids were long gone and the oppressor of the Jewish people was the Roman Empire. The Jerusalem Temple had been destroyed back in 70 CE, and now in 132 CE, a warrior called Shimon bar Kochva rallied the Jews again to fight off the Romans. He succeeded at first, managed to expel the Romans, minted new coins, and even cleared the Temple Mount to get ready for the Third Temple. Rabbi Akiva was convinced Shimon bar Kochva was the real deal, and declared him the presumptive messiah. He gave full backing for the rebellion. As we know, it didn’t end well. Rabbi Akiva was executed by the Romans, and lost 24,000 students in the conflict (as explained here).

Before his death, Rabbi Akiva managed to find five new students: Rabbi Meir, Rabbi Yehuda bar Ilai, Rabbi Yose ben Halafta, Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, and Rabbi Elazar ben Shammua. (That said, we have evidence that Rabbi Meir and Rabbi Shimon had been his students for some years prior already.) Rabbi Akiva did not have a chance to actually ordain them, so it was Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava that later did, and paid the ultimate price:

He went and sat between two great mountains, between two large cities; between the Sabbath boundaries of the cities of Usha and Shefaram, and there ordained five sages: Rabbi Meir, Rabbi Yehudah, Rabbi Shimon, Rabbi Yose, and Rabbi Elazar ben Shammua…

As soon as their enemies discovered them, Rabbi Yehudah ben Bava urged them: “My children, flee!” They said to him: “What will become of you, Rabbi?” He replied: “I will lie down before them like a stone which none can overturn.” It was said that the enemy did not stir from the spot until they had driven three hundred iron spears into his body, making it like a sieve… (Sanhedrin 14a)

Thanks to Rabbi Yehuda ben Bava’s martyrdom, the five new rabbis escaped with their lives. They went on to revive Judaism in the years following the Bar Kochva Revolt (Yevamot 62b). Of the five, one in particular stood out: Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai. He was the one that revealed the mystical teachings of Judaism, and gave over what would become the Zohar. These revolutionary teachings saved Judaism and kept the flame burning through centuries of persecution and exile.

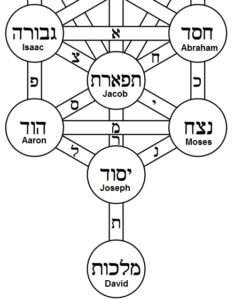

Reading the account of the Maccabees and the account of Rabbi Akiva’s students, one can’t but help see the striking parallels. Each revolt begins with a daring elder sage supporting an uprising against a powerful empire. Each describes Torah-observant, pious Jewish warriors hiding in caves and mountains and fighting guerrilla-style. In the case of the former, the Temple is purified and rededicated; in the case of the latter the Temple Mount is cleared and previous Roman plans to build an idolatrous shrine to Jupiter are halted. Five sons of Matityahu lead the war against the Greeks and save Judaism from extinction. Five students of Rabbi Akiva survive the war, lead the post-rebellion recovery, and save Judaism from extinction. The two sets of five have much in common, too:

Shimon the Maccabee goes on to set the foundations for a prosperous new Jewish kingdom, and for a proliferation of Torah learning. Shimon bar Yochai goes on to help produce the Mishnah, set the foundations for Kabbalah and the proliferation of the deepest dimensions of Torah. The initial leader of the Maccabees (and the greatest warrior overall) was Yehuda, while the initial leader of the students of Rabbi Akiva was Yehuda bar Ilai, who is actually the most-oft cited sage in the whole Mishnah! In both cases there is a Rabbi Elazar to “read aloud from the Holy Book” and call in God’s Name. Rabbi Akiva had a student named Yose, and it seems there is no such parallel among the Maccabees, until we remember that strange verse in II Maccabees cited above that calls Yochanan “Yosef”. I believe this is a cryptic allusion that Yochanan should be equated to Rabbi Akiva’s Yose (short for “Yosef”).

Coins depicting King Alexander I Balas

Finally, according to many opinions the illustrious Rabbi Meir actually had a different name, and meir was only a nickname because he was such a holy “illuminator”. The illustrious Yonatan was chosen from the brothers to serve as kohen gadol once the Temple was reclaimed, and held the post for some two decades as the conflict with the Greeks raged on. As kohen gadol, he henceforth stayed away from battle and focused on diplomacy. We know that Rabbi Meir, too, was not a big fan of Bar Kochva’s Revolt, and seems to have maintained good relations with the Romans. In fact, the Talmud tells us he once put on the garments of a Roman officer and went to free his sister-in-law from captivity (Avodah Zarah 18a). Meanwhile, we know that Yonatan was the first to ally with the Greeks, supporting up-and-comer Alexander Balas for the Seleucid throne, after which a grateful Balas invited Yonatan to his wedding and dressed him in royal Greek garments.

So, how do we make sense of the striking similarities between Matityahu and his five sons and Rabbi Akiva and his five students? Could it simply be history repeating itself? Or is it something more profound, perhaps a set of reincarnations for the purposes of tikkun? The major fault of the Maccabees was that, while they ensured the physical survival of the Jewish people, they did not do enough to preserve long-term spiritual success. Very quickly after them, their Hasmonean descendants became Hellenized, took on Greek names, and even persecuted rabbis. It is said that this is one reason why Hasmonean history—along with the Books of Maccabees—was suppressed by the Sages. (Chanukah is the only holiday without a Talmudic tractate devoted to it!)

With this in mind, one might suggest that God gave Matityahu and his five sons another chance, and the second time around they came to ensure the survival of the Jewish faith, the transmission of the Mishnah—most of which is relayed in the name of these six figures—as well as the transmission of major parts of Talmud, Midrash, and Kabbalah. In the second go, their military victory was not as successful, but the spiritual and moral victory was far greater, ensuring the long-term survival of the Jewish people.

Chag sameach!