In this week’s parashah, Beshalach, the Israelites finally leave Egypt. We read how Moses made sure to take with him ‘atzamot Yosef, the “bones of Joseph” (Exodus 13:19). It is interesting that a bone is called an ‘etzem (עצם), which literally means an “essence”. As an adjective, ‘atzum (עצום) means “strong”, as well as “shut” or “closed up”. This is fitting since bones are the strongest components of the body, and “closed up” within muscles and other tissues. (For those who like numbers, the gematria of עצום is 206, which is the total number of bones in the human body!) There is something especially significant about bones. God made Eve from Adam’s bone, and Adam later declared that Eve is “bone of my bone” (‘etzem mi’atzamai), implying that her essence is like his essence, and now he would finally be happy and no longer feel alone. What is so special about bones that they hold the very essence of a person?

One of the amazing wonders of biology is that each and every cell of our bodies contains our entire genome (except, of course, the reproductive cells). So, the DNA inside the nucleus of eye cells contains the genes that also program toenails, and the toes have the DNA of the retinal proteins in our eyes! It remains one of the great mysteries of biology how cells are able to control exactly which genes are turned “on” or “off” in every cell, and how they make sure that eyes don’t have nails, and nails don’t grow eyes. In our adult bodies, most cells have already been differentiated into something specific (like eyes or toes), but there is one place where cells remain undifferentiated, and could become anything. These are called stem cells, and they exist mainly within our bones. Here in the bone marrow, we do indeed find our ‘etzem, the core essence of who we are, still undifferentiated and full of potential to become anything.

This explains why God made Eve from Adam’s bone specifically, as if He took some of Adam’s undifferentiated stem cells to create Eve! This is precisely how a modern-day scientist experimenting with genetic engineering or organ printing would do it. Better yet, when scientists and surgeons need to extract bone marrow for stem cell transplants today, the rib bone is actually a great place to get them, since they are near the surface and easily accessible, with little meat around them. (I know that some people will quote a different opinion from our Sages, as in Berakhot 61a, that Eve was “split” from a two-faced Adam, or that she was made from his “tail”, but the rib opinion makes a great deal of sense from a scientific perspective.) In any case, when we remember that our bones contain our undifferentiated cells and our untampered DNA, we appreciate the beauty of divine Hebrew in calling a bone an “essence”.

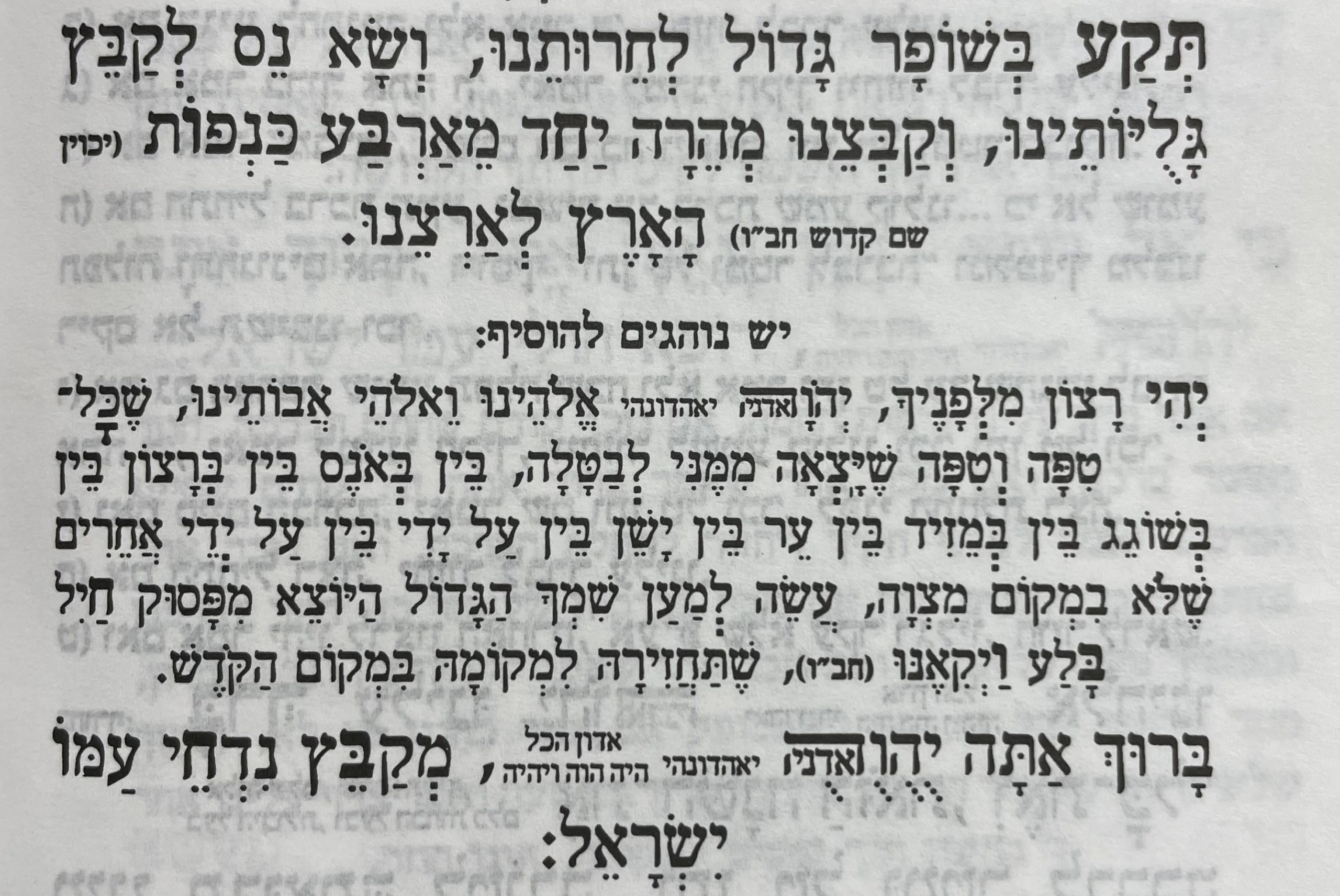

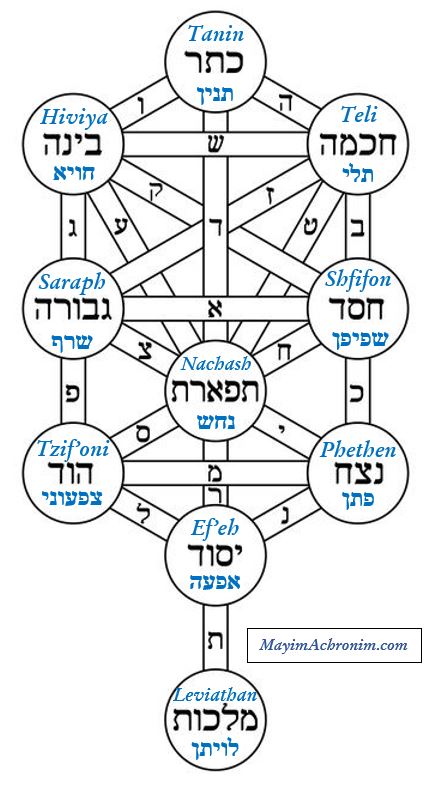

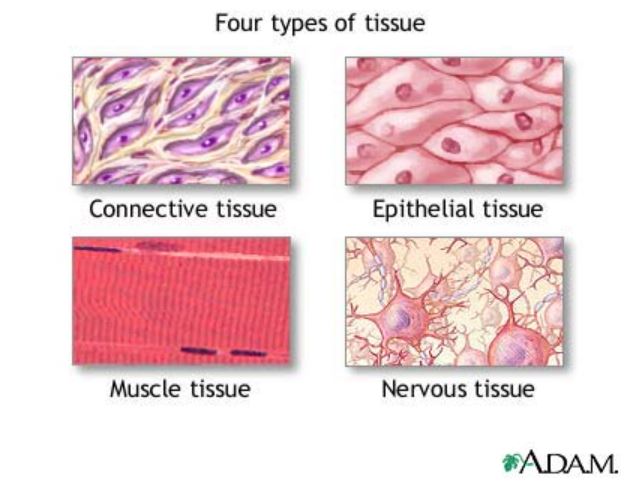

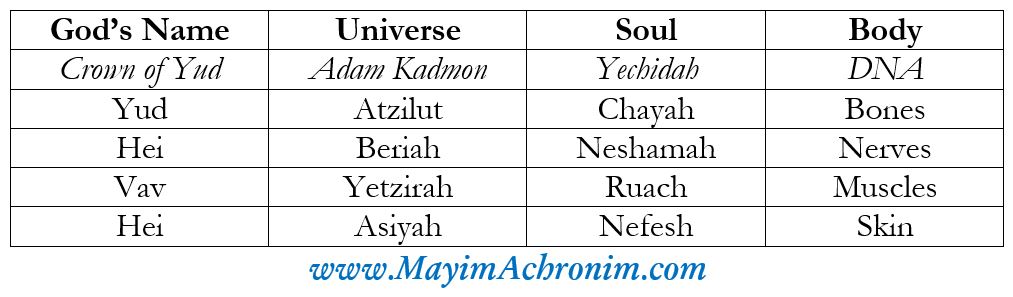

Scientifically speaking, the human body has four main types of tissues: bones are a type of connective tissue, and then there is muscle tissue, nervous tissue, and epithelial tissue. The Torah, too, speaks of four types of tissues: bones, plus bassar (meat), gidim (nerves), and ‘or (skin), neatly paralleling the four biological categories. We know that all fours in the Torah—such as the four mystical universes, the four Pardes aspects of Torah study, and the four letters of God’s Ineffable Name—match up and correspond to each other. We can link these up yet again with the four tissue types, to see once more the divine anatomy with which we were created:

Skin represents the surface level of Torah study, pshat (פשט), corresponding to the lowest realm, the physical and superficial Asiyah (as well as the lowest level of soul, the nefesh). Interestingly, the word in Hebrew to undress, ie. to remove one’s surface garments and reveal the skin, is lehitpashet (להתפשט)!

Beneath the skin is muscle, the bulkiest and heaviest part of the body, representing the sub-surface level of Torah study, remez, and the angelic realm of Yetzirah, as well as the next level of soul, ruach. The ruach is typically associated with the heart, also a muscle. With this we can understand why bassar (בשר), “flesh” or “meat”, shares a root with revealing news, levasser (לבשר)—for what is levasser but to reveal something currently hidden and as yet unknown? Levasser is to give more information beyond the obvious surface pshat that is already known! Moreover, we can now better understand why the Torah specifically uses the term yetzirah to describe the creation of Adam’s body (Genesis 2:7), and the command later for him to specifically become one bassar with his wife (2:24).

Going onwards, the muscles are innervated and controlled by nerves, paralleling drash, the metaphorical and allegorical level of Torah study, and the higher realm of Beriah, along with the neshamah level of soul. The neshamah is seated in the brain, the largest bundle of nerves in our body.

Finally, the inner-most part of the body is the bone, representing sod, the deepest part of Torah and its very essence. This is the level of soul called chayah, fitting because our Sages taught that Eve (made from Adam’s bone) was originally called Chayah, and only after the consumption of the Fruit did she become Chavah (see Kli Yakar on Genesis 3:20). The bone-sod level corresponds to the highest realm of God’s pure emanation, Atzilut. (The pure white colour of bone symbolically adds to this, along with the alliteration between Atzilut and ‘atzamot!) Atzilut is the place of pure, unadulterated light. Light is אור, with a value of 206, again like the total number of bones in the human body. We see a beautiful phonetic relationship between the surface level of skin, ‘or, spelled עור, and the deepest-most level of bone, corresponding to secret light, or, אור. (A word for an even more profound secret is raz, רז, with a value of 207, going one step further.) Without bones, the body would fall apart into a shapeless mass, just as would Torah without sod. (The Chida, Rabbi Chaim Yosef David Azulai [1724-1806] pointed out that if you take the sod out of Pardes [פרדס], you are left with pered [פרד], a mule!)

And what of the hidden-most “fifth” part—the “crown” atop the Yud of God’s Name and the yechidah soul, paralleling the most mysterious and mystical Adam Kadmon? Perhaps it’s the DNA itself, the very code that gives rise to all four tissue types of our bodies.

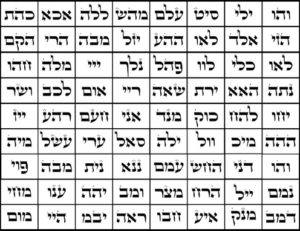

To summarize:

A final thought: Damage to the skin often heals back to the way it was before. Muscle and nerve damage is much harder to reverse, and sometimes irreparable. Bones, however, tend to heal back even stronger than they were. There is a wonderful lesson here for each of us, both individually and collectively as a nation: If something hurts us deeply and damages our very essence, we should bounce right back and recover, growing even stronger than we were before, so that our inner essence shines brighter than ever.

Shavua Tov and Happy Tu b’Shevat!

For more on ‘The Divine Anatomy of the Human Body’, see here.