This week’s Torah portion, Balak, is named after the Moabite king who sought to curse the Jewish people in the Wilderness. Seeing how the Hebrew nation had grown so large and powerful, and had earned God’s favour, Balak feared the Jews. He knew that taking them on physically would fail, so he decided on a spiritual solution to his problem. He summoned Bilaam (or Balaam), the greatest prophet among the gentiles, to curse the Jewish people in return for vast riches. Bilaam, however, refused the generous offer, knowing that there was no way he could curse the Jews if God did not wish it. Bilaam admitted that as a genuine prophet, he could only pronounce what Hashem would put in his mouth, and nothing more. Nonetheless, Balak continued to entice Bilaam until the prophet acquiesced, and agreed to give it a shot. Every single one of his attempts failed, and each time that Bilaam would open his mouth to curse the Jews, a blessing would emerge instead. Frustrated, Balak and Bilaam give up.

The story does not end there, though. Having failed to curse the Jews, Balak and Bilaam come up with another plan. Knowing that God’s favour only rests upon the Jews when they act righteously and in a holy manner, the two realized that they could tempt the Jews towards sin. Once the people are mired in sin, God’s divine protection would be lost, and the nation would in effect be cursed. This time, their plan worked like a charm.

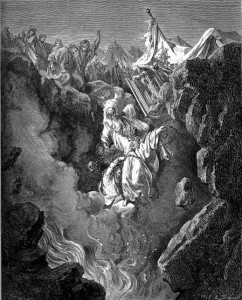

Balak and Bilaam sent a great number of gentile women to bring the Jewish men into sexual immorality and licentiousness. From there, they enticed them further into idolatry. Everything spins out of control, and Moses seems powerless to stop the endless cycle of sin. This reaches a climax when Zimri, the prince of the tribe of Shimon, publicly engages in sexual acts with a Midianite woman.

It is Pinchas, the grandson of Aaron, who finally steps in to end the tragedy. He slays Zimri, shocking the nation and waking the people. Pinchas is given an everlasting blessing for bringing an end to the immorality. According to some opinions, he later slays Bilaam as well. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 106a) states that it was precisely when Bilaam went to redeem his reward that he was killed.

Interestingly, all of the ancient texts agree that Bilaam was a true prophet, and was even equal in prophecy to Moses! How did Bilaam attain the merit for prophecy, and how did he fail so miserably?

The Origins of Bilaam

The Midrash relates how the gentiles brought a complaint against God. They argued that had God given them a leader like Moses, they too would have surely become holy and righteous nations. So, God did indeed send them a prophet like Moses. This was Bilaam.

In fact, the Arizal states that Moses and Bilaam stem from the same spiritual root: they were both reincarnations of Abel, the son of Adam (Sha’ar HaGilgulim, ch. 29). The spiritual spark corresponding to the letter Hei in Abel’s name (הבל) was given to Moses (משה), while the sparks corresponding to the letters Bet and Lamed in Abel’s name (הבל) were given to Bilaam (בלעם). So, it isn’t surprising that the two are often described as being of equal greatness in prophecy.

Unfortunately, the gentiles’ request for a prophet did not bring the result they had expected. Instead of using their prophet as a leader for goodness, they adopted him to further their own evil ends. And this began long before Balak summoned him.

The Talmud (ibid.) recounts how Bilaam was once one of the three main advisors and soothsayers to the Pharaoh in Egypt. The other two were Iyov (Job) and Yitro (Jethro). When Pharaoh’s astrologers saw that the Redeemer of the Hebrews would soon be born, it was Bilaam who advised that all the male firstborn be drowned. Job was against the idea, but remained silent. For this, he was so severely punished (as described in the Book of Job). Jethro was the only one who spoke up and tried to avert the decree. For his opposition to the Pharaoh, he was forced to flee the kingdom. In poetic fashion, the very redeemer he was trying to save at birth ended up being his own son-in-law! Bilaam, meanwhile, ended up working with Balak to try and finish the job he started over a century earlier. Once again, he failed.

A Balance in the Universe

The Midrash (Tanchuma on Balak, Passage 1) elaborates that for every great leader, king, or prophet that God had sent the Jews, he equally sent one to the non-Jews. King Solomon’s counterpart was Nebuchadnezzar. While the former used his talents to build the First Temple, a House for God and a place of holiness and unity, the latter used those same talents to destroy that very same holy place. King David’s counterpart was Haman. Both were blessed with wealth and success. The former used these resources to bring the people together and unify all the tribes, bringing peace to the region; the latter used his resources to incite a genocide. Moses’ counterpart was Bilaam. The former used his prophecy to bring God’s message of holiness, peace and goodness; the latter used his prophecy for idolatry, destruction, and immorality. The passage in the Midrash concludes that God subsequently took away all forms of prophecy from non-Jews. Bilaam was the last true prophet among the gentiles.