In this week’s parasha, Re’eh, Moses cautions the Israelites that they should observe every Torah mitzvah that he relayed to them, and not to add or detract from it (Deuteronomy 13:1). This always brings to mind the question of Rabbinic additions, expansions, fences, and stringencies that have been added to Jewish practice over the centuries. In light of the above verse, are such extras valid? Karaite Jews would argue with a resounding “no”, and this is why they stick to a strictly literal observance of the Torah.

The reality is that the Torah does also allow for the leaders and sages of future generations to make new rulings as necessary. Generally speaking, tough, such rulings must be based on something in the Torah itself, and rabbis are only attempting to extract the Torah’s true meaning and practice. Talmudic opinions are almost always supported by a Scriptural verse, even if it sometimes takes a lot of mental acrobatics to see how. We have 13 major rules of exegesis that the Sages followed in deriving rabbinic laws, and the general view is that the Sages did not invent anything new, but only rediscovered something lost:

The reality is that the Torah does also allow for the leaders and sages of future generations to make new rulings as necessary. Generally speaking, tough, such rulings must be based on something in the Torah itself, and rabbis are only attempting to extract the Torah’s true meaning and practice. Talmudic opinions are almost always supported by a Scriptural verse, even if it sometimes takes a lot of mental acrobatics to see how. We have 13 major rules of exegesis that the Sages followed in deriving rabbinic laws, and the general view is that the Sages did not invent anything new, but only rediscovered something lost:

In one passage, we are told that as soon as Moses passed away, some 3000 halakhot were forgotten (Temurah 16a). The Israelites asked Moses’ successor Joshua to get them back through prophecy, but he countered that no longer can laws be derived through prophecy—lo bashamayim hi! “The Torah is not in Heaven!” (Deuteronomy 30:12) Ultimately, Joshua’s successor Othniel was able to restore 1700 halakhot through the use of the 13 principles of exegesis. In other words, built into the Torah itself is the power to extract its true meaning, and to derive all laws, including rabbinical ones, from it.

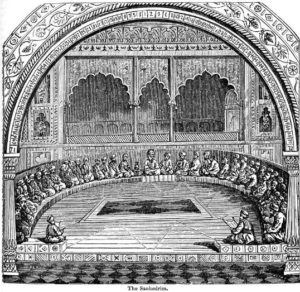

That said, sometimes laws are introduced without a Scriptural basis, presumably out of necessity. The most infamous case of this is the time when Beit Shammai took over the Sanhedrin by force and voted in 18 new decrees (see Shabbat 13b-17b and Yerushalmi Shabbat 1:4). It isn’t clear what exactly happened, and how it transpired. It began when the Sages of the day all went to visit one of the leading scholars, Chananiah ben Hizkiya ben Garon, who was ill at the time. (Ben Garon’s greatest achievements were composing a text called Megillat Ta’anit, and ensuring that the Book of Ezekiel remained in the Tanakh at a time when many Sages wanted it removed. He was able to resolve all apparent contradictions stemming from the Book of Ezekiel.)

While in Ben Garon’s attic, it turned out that the disciples of Shammai outnumbered the disciples of Hillel. As this was a valid convocation of rabbis, it would be permitted to vote in new laws. Beit Shammai took advantage of the opportunity, and brought in armed guards to block the entryway to the attic so that Beit Hillel could not escape. Then, they proposed 18 laws and voted them in by majority. The Talmud Bavli says that Hillel was made to sit in submission before Shammai, and this was a most shameful event. The Talmud Yerushalmi goes even further and says things got violent, and disciples of Shammai actually killed disciples of Hillel! Many refuse to believe that Torah sages literally harmed each other, and say the Talmud must be speaking figuratively. Whatever the case, both Talmuds assert that this day was as difficult and terrible for the Jewish people as the day of the Golden Calf. In fact, there used to be a fast day observed in commemoration of this tragedy, on the 9th of Adar (see Shulchan Arukh, Orach Chaim 580).

When did this event happen? There are two possibilities: the first is that it happened in the time of Hillel and Shammai, and this is supported by the language of the Bavli which suggests Hillel and Shammai were themselves present. Hillel’s life overlapped with that of the cruel King Herod. We know from both Jewish and historical sources that Herod persecuted the rabbis, which might explain why they had to make new rulings in secret, in places like the attic of Ben Garon. The other possibility is that it happened during the Great Revolt, shortly before the destruction of the Second Temple. By that point, the Sanhedrin could not convene in its proper quarters on the Temple Mount, which might also explain why they had to gather secretly in an attic. Moreover, we know that at the time there were Kanayim, “Zealots”, a faction of Beit Shammai that did indeed take up arms and sought to violently rule the streets of Jerusalem. This is more fitting with the Yerushalmi’s violent account. In addition, the Yerushalmi does not say Hillel and Shammai were there, but does suggest Rabbi Yehoshua and Rabbi Eliezer were there. Recall that Rabbi Yehoshua and Rabbi Eliezer were students of Rabban Yochanan Ben Zakkai, the leading sage at the time of the Temple’s destruction.

Rabbi Eliezer, who was stringent and more of a Shammai at heart (even though his main teacher Rabban Yochanan was a disciple of Hillel), believed that the 18 decrees of Beit Shammai were a good thing. They had “filled the measure”. His more lenient colleague Rabbi Yehoshua believed it was a terrible thing, and not only did they not fill the measure, they “erased” the measure! He thought that more stringencies were counterproductive, and instead of being a fence that preserves Judaism, would make Judaism too difficult to observe and drive people away. Not only will the unlearned majority stop keeping rabbinic laws, they will throw off the yoke of Torah entirely and stop keeping even Scriptural laws. In short, the masses will “throw out the baby with the bathwater”. Rabbi Yehoshua’s observation was prescient, and it seems history has confirmed his fears.

With that long introduction, what exactly were those 18 decrees?

“A Nation That Dwells Alone”

There are vast differences in opinion regarding the nature of the 18 laws. Both Talmuds present multiple lists, with varying items. Most of them tend to focus on purity laws that applied in Temple times but are not so relevant today. The list that is most applicable for us is given in the Talmud Yerushalmi (Shabbat 1:4) by Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, as follows:

Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai taught: On that day they decreed about [1] their bread, and [2] their cheese, and [3] their wine, and [4] their vinegar, and [5] their fish brine, and [6] their muries, and [7] their preserves, and [8] their parboiled food, and [9] their corned food, and [10] on split grain, and [11] on ground food, and [12] on peeled barley; [13] on their speech, and [14] on their testimony, and [15] on their gifts, [16] on their sons, and [17] on their daughters, and [18] on their firstlings.

First is the law of pat israel, to only consume bread that was made by Jews, or that a Jew participated in making at some point in the process. This is a stringency still observed by many today. Similarly, the second law was against gevinat akum, the “cheese of idolaters”. Until then, all cheese was considered kosher by default, since it can only be made from cow or goat milk (although there is a question regarding the kosher status of rennet). Henceforth, only cheese made by Jews or closely supervised by Jews would be kosher. This, too, is a law that is widely observed today. (Having said that, Italian Jews typically did not observe this stringency, and consumed all cheese.)

The related law of chalav israel—not consuming gentile-drawn milk—is derived by the Sages from this one about cheese, and the Talmud goes on to say that we are concerned cow or goat milk will be mixed with milk from non-kosher animals (like horses). For much of history, Jews in many locales were lenient with chalav israel, and typically did consume gentile milk, especially if it came from a trusted source. Today, because government bodies regulate milk in most developed countries, people have become even more lenient regarding milk and it is common to consume chalav stam.

The most widely accepted and well-known of the 18 is the prohibition against yayin stam, gentile-made wine. The Torah itself only forbids yayin nesech, wine that was used in idolatrous libations. (More accurately, the Rambam explains in his Sefer haMitzvot [Negative Mitzvah #194] that even the Torah itself does not prohibit idolatrous wine explicitly, but it is derived from a verse in parashat Ha’azinu where God admonishes the people for drinking idolatrous wine.) In that Ben Garon attic, Beit Shammai forbid all gentile wine. This has become standard halakhic practice today.

The Talmud Bavli concurs that gentile-made wine was one of the 18 decrees (Shabbat 17b). It also adds gentile-made oils. Oils are mentioned in the other Yerushalmi list, too. The oil ban is discussed in other places in the Talmud, where the Sages say that the prohibition on oils didn’t take effect because it was just way too difficult to keep (Avodah Zarah 36a). On the same page, the Talmud suggests that the ban on gentile wine and oil actually dates back to the prophet Daniel, though he had taken these stringencies only upon himself. Whatever the case, the one rule that all lists agree on without a doubt is the prohibition on “their daughters”, presumably meaning intermarriage. But wait, wasn’t intermarriage already forbidden from the Torah?

One minority opinion in the Yerushalmi suggests that the ban on “their daughters” is metaphorical, and actually just means on eating their eggs! In other words, there may have been a time when Jews only consumed eggs from Jewish-supervised hen houses. While intriguing, this is not the accepted opinion. Instead, the Sages explain that when the Torah banned intermarriage, it only meant specifically with the seven Canaanite nations. Beit Shammai decreed a ban on all intermarriage. In that case, what do we make of Ezra’s pronouncement for the Israelites returning to the Holy Land after the Babylonian Captivity to get rid of their foreign wives?

Some interpret the Torah to mean that it was originally forbidden to intermarry with Canaanites even if they converted to Judaism. All other nations were permitted to marry as long as they converted. Ezra’s pronouncement was against the wives that didn’t convert, or refused to convert. According to this view, Beit Shammai would have banned all intermarriage, even with converts. This really cannot be accurate. Bartenura (Rabbi Ovadia of Bertinoro, c.1445-1515) comments on Shabbat 1:4 that “their daughters” refers specifically to Samaritans, and it was intermarriage with Samaritans that was prohibited.

A different interpretation is given in the Talmud Bavli (Avodah Zarah 36b). Here we read that the ban on “their daughters” was not referring to marriage, but to any sexual intimacy with gentiles, even outside the context of marriage. In other words, before Beit Shammai’s decree, a Jewish man may have been allowed to be intimate with a gentile woman, and this is what was banned. The Talmud continues with a long series of back-and-forth arguments to show that truly, this was all prohibited already in the Torah itself. What Beit Shammai did was only to prohibit intimacy with gentiles even in private quarters and in secret—and this had already been instituted once before by the Hasmonean Maccabees, of Chanukah fame.

The Talmud adds here that the reason Beit Shammai made these decrees is to separate Jews from non-Jews and to lessen mingling between them. The ultimate goal was to prevent Jews from assimilating or falling to idolatry. (Keep in mind that at this time, two thousand years ago, “gentile” and “idolater” were basically interchangeable, since there were no other monotheistic religions around.) Beit Shammai banned gentile wine and bread so that Jews don’t go to non-Jewish parties. They made decrees on purity to further solidify the separation between Jews and idolaters. Perhaps Beit Shammai wanted Israel to live up to Bilaam’s words in the Torah that Israel is “a nation that dwells alone”. This was necessary because the Roman Empire was a huge melting pot, and many Jews were becoming Romans. (Including the Jewish-Roman general that destroyed the Temple, as explored in the past here.)

Having said all that, the rule in Judaism is that the law always follows Beit Hillel, so why were the decrees of Beit Shammai accepted at all?

“Halakhah K’Beit Hillel”

Presumably, the decrees of Beit Shammai were accepted because they were voted in by majority in a Sanhedrin-like council. However, the Talmudic narrative makes it quite clear that it was not a legitimate Sanhedrin. Beit Hillel were forced to vote, and perhaps were even violently suppressed. Beit Shammai took majority through an inappropriate ruse. How could such laws ever be passed or accepted? I think it is a likely possibility that they weren’t accepted.

If we date the event to the time of the Great Revolt—which makes more sense altogether—we can understand why Beit Shammai pushed these laws. Not only did they want to separate between Jews and Romans, but they also wanted to weed out Roman sympathizers and collaborators. They became uncharacteristically violent because they felt desperate times called for desperate measures. It is possible that this event led directly to Rabban Yochanan’s exit from Jerusalem. He got permission from Vespasian to establish a new school in Yavne. Rabban Yochanan was a Hillelite, as were his disciples. Now we can better understand why, henceforth, Beit Shammai basically ceased to exist.

However, there were among Rabban Yochanan’s students those who favoured more stringencies, like Rabbi Eliezer. They personally upheld the decrees of Beit Shammai, inspiring others to do the same. Over time, the stringencies became more and more commonplace, and some did become universally accepted. Since they became accepted, that became normative halakhah. The question for us today is: should we continue to observe these Shammaian practices, and should we encourage people to take on these stringencies? Do we side with Rabbi Eliezer, or with Rabbi Yehoshua? Shammai or Hillel?

The Talmud itself affirms that we never accept Beit Shammai (Berakhot 36b). In fact, the language there is that we don’t even consider their opinion to be valid! So why observe their decrees, especially in light of the horrible way they voted them in? It is intriguing to note the position of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, who spoke about this issue at length, explaining that Beit Shammai is all about potentials and not realities, and is rooted in the mystical side of Gevurah and Din, not Chessed—hence the reason for the complete rejection of Shammai (see, for instance, Likkutei Sichos, Vol. II, on Beshalach/Tu b’Shevat). Yet, Lubavitch is quite strict regarding things like chalav israel and gevinat akum! (Some explain it by finding other sources and explanations. However, it doesn’t change the fact that it is a Shammaian law!)

Another argument might be based on the oft-repeated idea that in the Messianic Age, the law will switch to follow Shammai. Since we are approaching that era, should we take these extras upon ourselves? Or should we do the very opposite, and rule on the side of Chessed at a time when the world clearly needs it.

A final note to keep in mind is that the Talmud (Avodah Zarah 36a) suggests that the 18 decrees of Beit Shammai actually cannot be repealed, even by the future Sanhedrin of Eliyahu! How could this be? (And, in that case, how was it that the prohibition on oils was rescinded?) And how do we make sense of all this in light of the famous Heavenly Voice that proclaimed, after three years of ceaseless debates, that the halakhah should always follow Beit Hillel? (Eruvin 13b)

I leave these questions unanswered, and will instead conclude with one more teaching of the Sages. A Tosefta in Eduyot 2:2 states that there are 24 instances where Beit Hillel is actually stricter than Beit Shammai. (The Jewish Encyclopedia counted 55 instances!) The Sages conclude by stating the following:

Forever the law follows Beit Hillel. One who wishes to take stringencies upon himself and follow the stringencies of both Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai, of him it is said: “A fool walks in darkness” (Ecclesiastes 2:14). However, one who takes on both the leniencies of Beit Shammai and the leniencies of Beit Hillel is wicked. Rather, one should either follow Beit Hillel—with their leniencies and stringencies—or follow Beit Shammai—with their leniencies and stringencies.

לעולם הלכה כדברי ב”ה והרוצה לעשות להחמיר על עצמו ולנהוג כחומרי ב”ה וכחומרי ב”ש על זה נאמר (קוהלת ה) והכסיל בחשך הולך התופס קולי ב”ש וקולי ב”ה ה”ז רשע אלא או כדברי ב”ה כקוליהן וכחומריהן או כדברי ב”ש כקוליהן וכחומריהן.

Shabbat Shalom!