The second book of the Torah, Shemot, begins by recounting the Israelite bondage in Egypt, and the Exodus that followed. One often overlooked question is: when did all of this actually happen? The Torah itself never gives any years or specific dates for its events. The accepted Jewish tradition is that the Exodus took place in the Hebrew year 2448, which corresponds to roughly 1312 BCE. What might archaeology and the historical record reveal?

City of Ramses

The Torah tells us that one of the major cities that the Israelites built was Ramses (Exodus 1:11). The historical record shows that this city was, not surprisingly, built by the pharaoh Ramses II (the Great). However, his reign spanned 1279-1213 BCE, too late for the Jewish dating of the Exodus. Perhaps it was Ramses’ grandfather, Ramses I – the founder of Egypt’s famous 19th dynasty – that began building a new capital city to be named after him. Ramses I reigned 1292-1290 BCE; still too late to coincide with Jewish tradition.

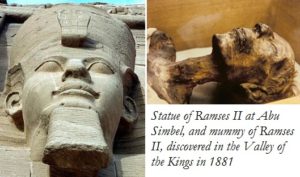

The Torah never identifies the names of any pharaohs it mentions. It describes at least three different ones: the pharaoh that dealt with Abraham, and the one that appointed Joseph many decades later, as well as the “new pharaoh” that forgot about Joseph’s contributions (Exodus 1:8). The pharaoh at the time of the Exodus was likely a different pharaoh altogether, too. The description we have of Ramses II actually parallels the Torah’s Exodus pharaoh quite well.

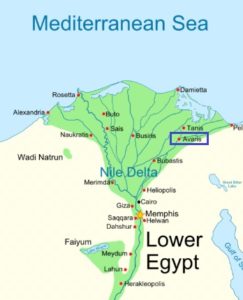

Ramses II was Egypt’s longest-reigning monarch (66 years!) and had over 100 children. He vastly expanded Egypt’s wealth, and stretched its territory and influence as far as the lands of Canaan and Syria. We see that he was a prolific builder, commissioning – among many other projects – a massive temple complex known as the Ramesseum, which still stood over 1000 years later when it marvelled the Greek historian Diodorus. His city of Ramses (or Pi-Ramses) was located in northeastern Egypt, in the land of Goshen, precisely where the Torah says the Israelites dwelled.

Ramses II was Egypt’s longest-reigning monarch (66 years!) and had over 100 children. He vastly expanded Egypt’s wealth, and stretched its territory and influence as far as the lands of Canaan and Syria. We see that he was a prolific builder, commissioning – among many other projects – a massive temple complex known as the Ramesseum, which still stood over 1000 years later when it marvelled the Greek historian Diodorus. His city of Ramses (or Pi-Ramses) was located in northeastern Egypt, in the land of Goshen, precisely where the Torah says the Israelites dwelled.

The Hyksos

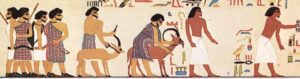

Images of Semites in Egypt, discovered in a Twelvth Dynasty tomb, dated to c. 1900 BCE

The historical record shows that a few centuries before Ramses, a mysterious Semitic tribe migrated to Egypt en masse and ended up taking over the kingdom. They were called heqa khaseshet, “foreign rulers”, which gave rise to the term “Hyksos”. Eventually, the Egyptians fought back and regained control from the foreigners. Most were expelled, many were killed, and it is likely that some were enslaved.

The ancient Jewish historian Josephus wrote that “Hyksos” comes from hekw shasu, “shepherd kings”. Of course, the Torah describes in detail how the Hebrews came down to Egypt and made sure everyone knew they were shepherds, a trade frowned upon in Egypt. Josephus cites historical sources suggesting that 480,000 Hyksos were ultimately expelled, and he concludes that these were the ancient Israelites!

It is interesting to point out that the Hyksos’s capital city was also in the northeastern region of Goshen. The city was named Avaris, or Hawara. These sound quite similar to the way the Egyptians refer to the Hebrews in the Torah: ivri.

Historians date the Hyksos period from 1638 to 1530 BCE, totalling just about 110 years. Amazingly, the Zohar (I, 212a-b) states that the Israelites ruled over Egypt for 110 years, then spent the remaining 290 years of their time in Egypt as slaves. This would mean that the Exodus happened 290 years after the end of the Hyksos period. Doing the math, 290 years after 1530 BCE takes us to 1240 BCE – right in the heart of the reign of Ramses II!

Solar Eclipse

‘Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still upon Gibeon’ by John Martin

All of the above suggests that the Exodus happened closer to the middle of the 13th century BCE. Recently, Israeli scientists discovered what may have been Joshua’s famous “stopping of the Sun” at the Battle of Gibeon (as described in the Book of Joshua, chapter 10). Interpreting this event as a solar eclipse, scientists at Ben Gurion University used NASA data to find any solar eclipses that may have been seen in the area between 1500 and 1000 BCE. They found exactly one, which took place on October 30, 1207 BCE.

This is incredible because the Battle of Gibeon would have happened roughly 40 years after the Exodus (since the Israelites spent 40 years in the Wilderness before Joshua led them to the Promised Land). If the Exodus took place around 1240 BCE, as we suggested above, then the dating of Joshua’s battle and the solar eclipse is right on target!

Reconciliation

The major issue now is that 1240 BCE seems to contradict the traditional Jewish dating of 1312 BCE. The truth is that Ancient Egyptian chronology is notoriously inaccurate. Scholars admit that discrepancies do exist, and are off by anywhere from 30 to 300 years. The discrepancy in our case is only about 70 years, well within the margins of errors.

Compared to the many foggy lists that scholars use to put together Egyptian chronology, the Torah’s chronology is fairly consistent and straight-forward. The years are added up based on peoples’ lifespans and the ages at which they had children, which are explicitly recorded. Historians might therefore want to take another look at Jewish chronology (as brought down in Seder Olam) if they wish to resolve some of their own conflicts.

And did the Jews build the pyramids? They may have built some pyramids (although by that time, pyramids had gone out of style). However, the famous Great Pyramid of Giza was completed by the middle of the third millennium BCE, long before any Israelites were on the scene.

The above article is adapted from Garments of Light: 70 Illuminating Essays on the Weekly Torah Portion and Holidays. Click here to get the book!