Chanukah is the only major Jewish holiday without an explicit basis from the Tanakh. However, there does exist an ancient Book of Maccabees—which recounts the history of Chanukah and the chronicles of Matityahu, Judah and the Hashmonean brothers—but it was not included in the Tanakh. Some say it was not included because by that point (2nd century BCE), the Tanakh had already been compiled by the Knesset haGedolah, the “Great Assembly” which re-established Israel after the Babylonian Exile. Others argue that the Tanakh was not completely sealed by the Knesset, since it appears that the Book of Daniel may have been put together around the same time as the Book of Maccabees, but was included in the Tanakh. This may be why Daniel was included in the Ketuvim, and not in the Nevi’im where we might expect it to be. Later still, the Sages of the Talmud debate whether certain books (such as Kohelet, “Ecclesiastes”, and Shir HaShirim, the “Song of Songs”) should be included in the Tanakh.

The simplest reason as to why the Book of Maccabees was not added to the Tanakh is probably because it is not a prophetic work, but simply a historical one. Another reason is that the original Hebrew text had been lost, and only Greek translations survived. It is also possible that the Book of Maccabees was not included for the same reason why there is no Talmudic tractate for Chanukah, even though there is a tractate for every other major holiday. (Chanukah is discussed in the Talmud in the tractate of Shabbat). Some argue that the events of Chanukah were so recent at the time that everyone knew them well, so having a large tractate for Chanukah was simply unnecessary. The other, more likely, reason is that although the Hashmonean Maccabees were heroes in the Chanukah period, they soon took over the Jewish monarchy (legally forbidden to them since they were kohanim) and actually adopted the Hellenism that they originally fought so valiantly against!

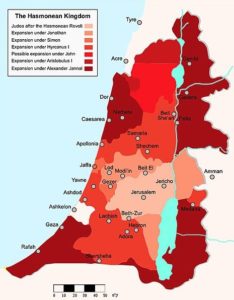

The first Hashmonean to rule was Shimon, one of the five sons of Matityahu. He was the only son to survive the wars with the Seleucid Greeks. He became the kohen gadol (high priest), and took the title of nasi, “leader” or “prince”, though not a king. Despite being a successful ruler, Shimon was soon assassinated along with his two elder sons. His third son, Yochanan, took over as kohen gadol.

The first Hashmonean to rule was Shimon, one of the five sons of Matityahu. He was the only son to survive the wars with the Seleucid Greeks. He became the kohen gadol (high priest), and took the title of nasi, “leader” or “prince”, though not a king. Despite being a successful ruler, Shimon was soon assassinated along with his two elder sons. His third son, Yochanan, took over as kohen gadol.

Yochanan saw himself as a Greek-style king, and took on the regnal name Hyrcanus. His son, Aristobulus (no longer having a Jewish name at all!) declared himself basileus, the Greek term for a king, after cruelly starving his own mother to death. Aristobulus’ brother, Alexander Jannaeus (known in Jewish texts as Alexander Yannai) was even worse, starting a campaign to persecute rabbis, including his brother-in-law, the great Shimon ben Shetach. Ultimately, Yannai’s righteous wife Salome (Shlomtzion) Alexandra ended the persecution, brought her brother Shimon and other sages back from exile in Egypt, and ushered in a decade of prosperity. It was Salome that re-established the Sanhedrin, opened up a public school system, and mandated the ketubah, a marriage document to protect Jewish brides. After her death, the kingdom fell apart and was soon absorbed by Rome.

Sadducees and Pharisees

While Alexander Yannai was aligned with the Sadducees, Salome Alexandra was, like her brother Shimon ben Shetach, a Pharisee. The Sadducees (Tzdukim) and Pharisees (Perushim) were the two major movements or political parties in Israel at the time. The former only accepted the written Torah as divine, while the latter believed in an Oral Tradition dating back to the revelation at Sinai. Thus, “Rabbinic Judaism” as we know it today is said to have developed from Pharisee Judaism, though this is not quite certain. The Sages of the Talmud didn’t speak so highly of the Pharisees in general, and Judaism also includes key elements from another major group that flourished at the time, the Essenes.

Because the Sadducees only accepted the written Torah, their observance was highly dependent on the Temple and the land of Israel, since most of the Torah is concerned with sacrificial and agricultural laws. When the Romans ultimately destroyed the Temple and the majority of Jews went into exile, Sadducee Judaism simply could not survive. (Later, a similar movement based solely on the written Torah, Karaite Judaism, would develop.) Meanwhile, the Pharisees and their Oral Tradition continued to develop, adapt, and flourish in exile and, together with Essene practices, gave rise to the Judaism of today.

Avot d’Rabbi Natan states that the Sadducees get their name from one Tzadok, a student of the sage Antigonus. Antigonus famously taught (Pirkei Avot 1:3) that one should serve God simply for the sake of serving God, and not in order to receive a reward in the afterlife. It is this teaching that led to Tzadok’s apostasy. Indeed, we know that the Sadducees did not believe in the Resurrection of the Dead or apparently any kind of afterlife at all. This makes sense, since the Sadducees only accepted the Chumash as law, and the Chumash itself never mentions an afterlife explicitly.

In that same first chapter of Pirkei Avot, we read that Antigonus was the student of Shimon haTzadik, the last survivor of the Knesset HaGedolah. Antigonus passed down the tradition to Yose ben Yoezer and Yose ben Yochanan, who passed it down to Yehoshua ben Perachiah and Nitai haArbeli, who passed it down to Shimon ben Shetach and Yehuda ben Tabai. This means that Shimon ben Shetach, brother of Queen Salome Alexandra, lived only three generations after Shimon haTzadik, the last of the Great Assembly. This presents a problem since, according to traditional Jewish dating, the Great Assembly was about 300 years before the rule of Salome. (It is even more problematic according to secular dating, which calculates nearly 500 years!) It is highly unlikely that three generations of consecutive sages could span over 300 years.

The rabbinic tradition really starts with Shimon haTzadik, the earliest sage to be cited in the Talmud. He is said to have received the tradition from the last of the prophets in the Great Assembly, thus tying together the rabbinic period with the Biblical period of prophets. Yet, Shimon haTzadik himself is not called a “rabbi”, and neither is his student Antigonus, or Antigonus’ students, or even Hillel and Shammai. The title “rabban” is later used to refer to the nasi of the Sanhedrin, while the first sages to properly be called “rabbi” are the students of Rabban Yochanan ben Zakkai, the leader at the time of the Temple’s destruction by the Romans.

Despite this, the title “rabbi” is often applied retroactively to earlier sages, including Shimon ben Shetach, Yehoshua ben Perachiah, and others, all the way back to Shimon haTzadik, the first link in the rabbinic chain. Who was Shimon haTzadik?

The Mystery of Shimon haTzadik

The most famous story of Shimon haTzadik is recounted in the Talmud (Yoma 69a). In this story, Alexander the Great is marching towards Jerusalem, intent on destroying the Temple (due to the activism of a group of Kutim), so Shimon goes out to meet him in his priestly garments (he was the kohen gadol). When Alexander sees him, he halts, gets off his horse, and bows down to the priest. Alexander’s shocked generals ask why he would do such a thing, to which Alexander responds that he would see the face of Shimon before each successful battle.

While it is highly doubtful that the egomaniacal Alexander (who had himself declared a god) would ever bow down to anyone, this story is preserved in a number of texts, including that of Josephus, the first-century historian who was an eye-witness to the Temple’s destruction. In Josephus, however, it is not Shimon who meets Alexander, but another priest called Yaddua. Yaddua is actually mentioned in the Tanakh (Nehemiah 12:22), which suggests he was a priest in the days of the Persian emperor Darius. Of course, it was Darius III whom Alexander the Great defeated. It seems Josephus’ account is more accurate historically in this case.

In fact, in Sotah 33a, the Talmud tells another story of Shimon haTzadik, this one during the reign of the Roman emperor Caligula. We know that Caligula reigned between 37 and 41 CE—over three centuries after Alexander the Great! The Talmud thus gives us three different time periods for the life of Shimon haTzadik: a few generations before Shimon ben Shetach, or a few centuries before in the time of Alexander the Great, or centuries after in the time of Caligula. Which is correct?

The First Rabbi

The Book of Maccabees (I, 2:1-2) introduces the five sons of Matityahu in this way:

In those days, Matityahu ben Yochanan ben Shimon, a priest of the descendants of Yoariv, left Jerusalem and settled in Modi’in. He had five sons: Yochanan, called Gaddi; Shimon, called Thassi; Yehuda, called Maccabee; Elazar, called Avaran; and Yonatan, called Apphus.

Each of the five sons of Matityahu has a nickname. The second son, Shimon, is called “Thassi” (or “Tharsi”). This literally means “the wise” or “the righteous”, aka. HaTzadik. It was Shimon who survived the Chanukah wars and re-established an independent Jewish state. In fact, the Book of Maccabees (I, 14:41-46) tells us:

And the Jews and their priests resolved that Shimon should be their leader and high priest forever until a true prophet should appear… And all the people agreed to decree that they should do these things to Shimon, and Shimon accepted them and agreed to be high priest and general and governor of the Jews…

Apparently, Shimon was appointed to lead the Jews by a “great assembly” of sorts, which nominated him and, after his acceptance, decreed that he is the undisputed leader. The Book of Maccabees therefore tells us that Shimon the Maccabee was a righteous and wise sage, a high priest, and leader of Israel that headed an assembly. This is precisely the Talmud’s description of Shimon haTzadik!

Perhaps over time the “great assembly” of Shimon was confused with the Great Assembly of the early Second Temple period. This may be why Pirkei Avot begins by stating that Shimon haTzadik was of the Knesset haGedolah. In terms of chronology, it makes far more sense that Shimon haTzadik was Shimon Thassi—“Simon Maccabeus”—who died in 135 BCE. This fits neatly with Shimon ben Shetach and Salome Alexandra being active a few generations later, in the 60s BCE as the historical record attests. It also makes sense that Shimon haTzadik’s student is Antigonus, who carries a Greek name, just as we saw earlier that following Shimon the leaders of Israel were adopting Greek names.

Thus, of the three main descriptions of Shimon haTzadik in the Talmud, it is the one in Avot that is historically most accurate, and not so much the one in Yoma (where he is placed nearly three centuries before Shimon ben Shetach) or the one in Sotah (where he is in the future Roman era). Thankfully, there is actually one more brief mention of Shimon haTzadik in the Talmud (Megillah 11a) which says Shimon haTzadik was one of the heroes of Chanukah! This is certainly the most accurate reference to the mysterious Shimon haTzadik in the Talmud, and puts him exactly in the right era! This Talmud confirms that Shimon haTzadik was “Shimon Thassi”, the Maccabee.

Lastly, we must not forget that Shimon the Maccabee was one of the instigators of the revolt against the Greeks and their Hellenism. He was the son of Matityahu, a religious, traditional priest, who fled Jerusalem when it was taken over by Hellenizers (as we quoted above, I Maccabees 2:1). Shimon was certainly aligned with the traditional Pharisees, and it was only his grandson Alexander Yannai who turned entirely to the more Hellenized Sadducees and began persecuting the Pharisees. As Rabbinic Judaism came out of Pharisee Judaism, it makes sense that the tradition begins with Shimon the Maccabee, or Simon Thassi, ie. Shimon haTzadik.

Interestingly, the Book of Maccabees states that Matityahu was a descendent of Yoariv. This name is mentioned in the Tanakh. I Chronicles 24:7 lists Yoariv as the head of one of the 24 divisions of kohanim, as established in the days of King David. The same chapter states that Yoariv was himself a descendent of Elazar, the son of Aaron the first kohen. Thus, there is a fairly clear chain of transmission from Aaron, all the way down to Matityahu, and his son Shimon.

Shimon continued to pass down the tradition, not to his son Yochanan—who was swayed by the Greeks and became John Hyrcanus—but to his student Antigonus. (Depending on how one reads Avot, it is possible that Yose ben Yoezer and Yose ben Yochanan were also direct students of Shimon haTzadik.) It appears we have found the historical Shimon haTzadik, and closed the gap on the proper chronology of the Oral Tradition dating back to Sinai.

If this is the case, then Chanukah is a celebration of not only a miraculous victory over the Syrian Greeks, but of the very beginnings of Rabbinic Judaism as we know it, with one of Chanuka’s central heroes being none other than history’s first official rabbi.

Chag sameach!