In the early morning hours before Yom Kippur, many Jews will seek to perform the custom of kapparot, which involves taking a live rooster (or chicken), swinging it over one’s head, and then having it slaughtered. In the process, the person states how the rooster will be their “atonement”, and while the rooster will die, the person will go on to live a good life. The rooster’s meat is typically donated. Others swing money over their heads instead of a rooster, and then donate the money to charity. Of course, this strange-sounding custom is not mentioned anywhere in the Torah or Talmud. In fact, throughout history many Jewish Sages tried hard to extinguish this custom, for a number of important reasons.

19th Century Lithograph of Kapparot

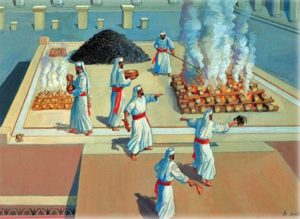

First of all, kapparot sounds much too similar to a korban, a sacrificial offering. In the days of the Temple, the kohanim sacrificed animals in order to atone for the people. The kapparot ritual explicitly states that the rooster serves as atonement, and the rooster is then killed. Despite some people’s claims that kapparot is not a true sacrifice, it clearly mimics the Temple’s sacrificial procedures, and intends to accomplish the same goal. The Mishnah Berurah (605:2) openly admits this, saying that kapparot is basically like a sacrifice. Indeed, an outsider would hardly be able to tell the difference. The problem is that the Torah forbids bringing sacrifices anywhere other than the place that God specifically designates (Deut. 12:5-6), which was the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. The Torah also commands that only kohanim are allowed to oversee sacrificial procedures. From this perspective alone, kapparot is contrary to the Torah.

Thirteen Years of Pain

Secondly, kapparot fits squarely under the category of unnecessary cruelty to animals. Commenting on the verse in Psalms (145:9) which states that God has mercy and compassion upon all of His creations, Rav Shimshon Raphael Hirsch wrote:

Here you are faced with God’s teaching which obliges you not only to refrain from inflicting unnecessary pain on any animal, but to help and, when you can, to lessen the pain whenever you see an animal suffering, even through no fault of yours.

(Horeb, Chapter 60, Section 416)

The Jewish Sages have always been concerned about animal welfare. The Talmud considers it a Torah mitzvah to treat animals with respect and prevent any harm to them (Bava Metzia 32b), so much so that one is allowed to violate various Shabbat prohibitions to help a suffering animal (Shabbat 128b). Let us not forget the story of Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi, who suffered excruciating pains for thirteen years. Why was he afflicted with such pain?

A calf was being taken to the slaughter when it broke away, hid its head under [Rabbi Yehuda’s] clothes, and lowed [in terror]. “Go”, he said, “for this you were created.” Thereupon it was said [in Heaven], “Since he has no pity, let us bring suffering upon him.”

(Bava Metzia 85a)

The great Rabbi Yehuda – the compiler of the Mishnah – made one uncompassionate remark to a fearful calf that was about to be slaughtered. For this, Heaven rained upon him tremendous pain – six years of kidney stones, and seven of scurvy, so unbearable that his cries could be heard over three miles away. When did his suffering end?

One day [Rabbi Yehuda’s] maidservant was sweeping the house; [seeing] some young weasels lying there, she made to sweep them away. “Let them be,” he said to her; “It is written, ‘And his tender mercies are over all his works.’” It was said [in Heaven], “Since he is compassionate, let us be compassionate to him.”

Rabbi Yehuda quotes the same verse (Psalms 145:9) that Rav Hirsch expounded upon, and has mercy on the young animals in his home. For this, his suffering is finally taken away. If even one little remark to an animal is worth thirteen years of suffering, how much more so if an animal is swung around wildly, then slaughtered needlessly – which is precisely what happens with kapparot. (It has also been pointed out that chickens used in kapparot are usually starving and thirsty, and often have their limbs dislocated or bones broken during the procedure.)

Idolatrous Practices

Lastly, kapparot appears to be connected with various idolatrous practices and non-Jewish customs. The Ramban, among others, considered it darkei emori, the way of idolaters. The Shulchan Arukh, the central halachic text of Judaism, is also staunchly opposed to kapparot, and its author, Rabbi Yosef Karo, called it a “foolish custom”.

Many modern-day authorities, too, from across the Torah-observant world, have been vocally against kapparot. Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik and the entire Brisker rabbinic lineage before him opposed the custom, considering it irrational. The rabbi of Beit El and rosh yeshiva of Ateret Yerushalaim, Shlomo Chaim Aviner, a prominent authority within the Dati Leumi community, has described it as a “superstition”. And the former Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv, Chaim David HaLevy, beautifully wrote in his Aseh Lekha Rav:

Why should we, specifically on the eve of the holy day of Yom Kippur, be cruel to animals for no reason, and slaughter them without mercy, just as we are about to request compassion for ourselves from the living God?

Kapparot with Money

While it is clearly evident that one should completely avoid kapparot with chickens, some might argue that it is still worth doing kapparot with money. The problem is that the procedure and text are still the same: waving coins or bills over one’s head, stating that the money serves as an atonement, and that donating it will save one’s life.

The truth is that there is no need to do this at all, since any giving to charity automatically fulfils a mitzvah, assists in one’s repentance and atonement, and is said to be life-saving. The Talmud famously tells us (Bava Batra 10a) that charity is the greatest of all forces, and quotes the verse in Proverbs that “charity saves from death” (10:2).

Thus, any charitable contribution, at any time of the year, already does what kapparot claims to do. And so, awkwardly waving money around one’s head and reciting the kapparot verses is nothing more than a funny-looking waste of time, associated with a cruel, idolatrous, nonsensical, and non–Jewish custom.

In his list of the 613 Torah mitzvot, the Rambam (who was also opposed to kapparot) lists the 185th positive commandment of the Torah as eradicating any traces of idolatry from Israel. Since many great Sages held the view that kapparot is associated with idolatrous ways, including the Ramban, Rashba, and the authoritative Shulchan Arukh, it is undoubtedly a mitzvah to not only avoid kapparot, but to encourage others to abandon this practice, and to expunge it from Judaism.

The article above is adapted from Garments of Light – 70 Illuminating Essays on the Weekly Torah Portion and Holidays. Click here to get the book!