In this week’s parasha, Va’era, we read about the first seven plagues to strike Egypt. These were brought about through the Staff of Moses, as were the later Splitting of the Sea, the victory over Amalek (Exodus 17) and the water brought forth from a rock. What was so special about this particular staff, and what was the source of its power?

In this week’s parasha, Va’era, we read about the first seven plagues to strike Egypt. These were brought about through the Staff of Moses, as were the later Splitting of the Sea, the victory over Amalek (Exodus 17) and the water brought forth from a rock. What was so special about this particular staff, and what was the source of its power?

Pirkei Avot (5:6) famously states that the Staff was one of ten special things to be created in the twilight between the Sixth Day and the first Shabbat. The Midrash (Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer, ch. 40) elaborates:

Rabbi Levi said: That staff which was created in the twilight was delivered to the first man out of the Garden of Eden. Adam delivered it to Enoch, and Enoch delivered it to Noah, and Noah to Shem. Shem passed it on to Abraham, Abraham to Isaac, and Isaac to Jacob, and Jacob brought it down to Egypt and passed it on to his son Joseph, and when Joseph died and they pillaged his household goods, it was placed in the palace of Pharaoh.

And Jethro was one of the magicians of Egypt, and he saw the staff and the letters which were upon it, and he desired it in his heart, and he took it and brought it, and planted it in the midst of the garden of his house. No one was able to approach it any more.

When Moses came to his house, he went into Jethro’s garden, and saw the staff and read the letters which were upon it, and he put forth his hand and took it. Jethro watched Moses, and said: “This one in the future will redeem Israel from Egypt.” Therefore, he gave him Tzipporah his daughter to be his wife…

God gave the staff to Adam, who gave it to Enoch (Hanokh)—who later transformed into the angel Metatron—and Enoch passed it on further until it got to Joseph in Egypt. The Pharaoh confiscated it after Joseph’s death. The passage then alludes to another Midrashic teaching that Jethro (Yitro), Moses’ future father-in-law, was once an advisor to Pharaoh, along with Job and Bila’am (see Sanhedrin 106a). The wicked Bila’am was the one who advised Pharaoh to drown the Israelite male-born in the Nile. While Job remained silent (for which he was so severely punished later), Jethro protested the cruel decree, and was forced to resign and flee because of it. As he fled, he grabbed the divine staff with him. Arriving in Midian, his new home, Jethro stuck the staff in the earth, at which point it seemingly gave forth deep roots and was immovable.

A related Midrash states that all the suitors that sought the hand of his wise and beautiful Tzipporah were asked to take the staff out of the earth, and should they succeed, could marry Jethro’s daughter. None were worthy. (Not surprisingly, some believe that this Midrash may have been the source for the Arthurian legend of the sword Excalibur.) Ultimately, Moses arrived and effortlessly pulled the staff out of the ground.

The passage above states that Moses was mesmerized by the letters engraved upon the staff, as was Jethro before him. What were these letters?

The 72 Names

Targum Yonatan (on Exodus 4:20) explains:

And Moses took the rod which he had brought away from the chamber of his father-in-law, made from the sapphire Throne of Glory; its weight forty se’ah; and upon it was engraved and set forth the Great and Glorious Name by which the signs should be wrought before Hashem by his hand…

God’s Ineffable Name was engraved upon the sapphire staff, which was itself carved out of God’s Heavenly Throne. The staff weighed a whopping 40 se’ah, equivalent to the minimum volume of a kosher mikveh, which is roughly 575 litres (or 575 kilograms) of water. (This might explain why none could dislodge the staff, except he who had God’s favour.)

A parallel Midrash (Shemot Rabbah, 8:3) also confirms that the staff was of pure sapphire, weighing forty se’ah, but says it was engraved with the letters that stand for the Ten Plagues, as we recite at the Passover seder: datzach, adash, b’achav (דצ״ך עד״ש באח״ב).

A final possibility is that the “Great and Glorious Name by which the signs should be wrought” refers to the mystical 216-letter Name of God (or 72-word Name of God). This Name is actually 72 linked names, each composed of three letters. The names are derived from the three verses Exodus 14:19-21:

And the angel of God, who went before the camp of Israel, removed and went behind them; and the pillar of cloud removed from before them, and stood behind them; and it came between the camp of Egypt and the camp of Israel; and there was the cloud and the darkness here, yet it gave light by night there; and the one came not near the other all the night. And Moses stretched out his hand over the sea; and Hashem caused the sea to go back by a strong east wind all the night, and made the sea into dry land, and the waters were divided.

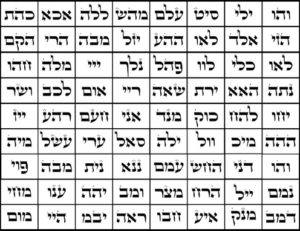

The 72 Three-Letter Names of God

Each of these verses has exactly 72 letters. Hidden within them is this esoteric Name of God, the most powerful, through which came about the miracle of the Splitting of the Sea as the verses themselves describe. The Name (or 72 Names) is derived by combining the first letter of the first verse, then the last letter of the second verse, and then the first letter of the third verse. The same is done for the next letter, and so on, for all 72 Names.

Since the Splitting of the Sea and the plagues were brought about through these Names, the Midrash above may be referring not to the Ineffable Name, but to these 72 Names as being engraved upon the Staff. In fact, it may be both.

Staff from Atzilut

The 72 Names are alluded to by another mystical 72-Name of God. The Arizal taught that God’s Ineffable Name can be expanded in four ways. This refers to a practice called milui,* where the letters of each word are themselves spelled out to express the inner value and meaning of the word. God’s Ineffable Name can be expanded in these ways, with the corresponding values:

יוד הא ואו הא = 45

יוד הה וו הה = 52

יוד הי ואו הי = 63

יוד הי ויו הי = 72

The Name with the 72 value is the highest, not just numerically, but according to the sefirot, partzufim, and universes laid out in Kabbalah. The 52-Name corresponds to Malkhut and the world of Asiyah; the 45-Name to Zeir Anpin (the six “masculine” sefirot) and the world of Yetzirah; and the 63-Name to Binah and the world of Beriah. The 72-Name—which is, of course, tied to the above 72 Names of God—corresponds to the highest universe, Atzilut, the level of God’s Throne, where there is nothing but His Emanation and Pure Light. Here we come full circle, for the Midrash states that the Staff of Moses was itself carved out of God’s Throne. This otherworldly staff came down to this world from the highest Heavenly realm!

Where is the Staff Today?

What happened to Moses’ staff after his passing? Another Midrash (Yalkut Shimoni, Psalms 869) answers:

…the staff with which Jacob crossed the Jordan is identical with that which Judah gave to his daughter-in-law, Tamar. It is likewise the holy staff with which Moses worked, and with which Aaron performed wonders before Pharaoh, and with which, finally, David slew the giant Goliath. David left it to his descendants, and the Davidic kings used it as a sceptre until the destruction of the Temple, when it miraculously disappeared. When the Messiah comes it will be given to him for a sceptre as a sign of his authority over the heathens.

This incredible passage contains a great deal of novel insight. Firstly, Jacob used this divine staff to split the Jordan and allow his large family to safely cross back to Israel, just as the Israelites would later cross the Jordan in miraculous fashion under the leadership of Joshua. It seems Joshua himself, as Moses’ rightful successor, held on to the staff, and passed it down through the Judges and Prophets until it came to the hand of David. Unlike the traditional account of David slaying Goliath with the giant’s own sword (after the slingshot), the Midrash here says he slew Goliath with the staff!

The staff remained in the Davidic dynasty until the kingdom’s end with the destruction of the First Temple. At this point a lot of things mysteriously disappeared, most famously the Ark of the Covenant. It is believed that the Ark was hidden in a special chamber built for it by Solomon, who envisioned the day that the Temple would be destroyed. It is likely that the staff is there, too, alongside the Ark.

Mashiach will restore both of these, and will once again wield the sceptre of the Davidic dynasty. As the staff is forged from God’s own Heavenly Throne, it is fitting that Mashiach—God’s appointed representative, who sits on His corresponding earthly throne—should hold a piece of it. And this symbol, the Midrash concludes, will be what makes even the heathens accept Mashiach’s—and God’s—authority. Jacob prophesied this on his deathbed (Genesis 49:10), in his blessing to Judah:

The sceptre shall not depart from Judah, nor the ruler’s staff from between his feet, until the coming of Shiloh; and unto him shall the obedience of all the peoples be.

Shiloh is one of the titles for Mashiach (see Sanhedrin 98b), and his wielding of the staff will bring about the obedience of all the world’s people to God’s law. We can now also solve a classic problem with the above verse:

The verse states that the sceptre will not depart from Judah until the coming of Mashiach, as if it will depart from Judah when Mashiach comes. This makes no sense, since Mashiach is a descendent of Judah! It should have simply said that the sceptre shall never depart from Judah, from whom the messiah will come. Rather, Jacob is hinting that the Staff will one day be hidden in the land of Judah, deep below “between his feet”, and won’t budge from there for millennia until Mashiach comes and finally restores it.

May we merit to see it soon.

*Interestingly, using the same milui method, one can expand the word staff (מטה) like this: מאם טאת הה, which is 501, equivalent to דצ״ך עד״ש באח״ב, the acronym for the Ten Plagues which the Staff brought about!

The above is an excerpt from Garments of Light, Volume Two. Get the book here!