Tisha b’Av is the saddest day on the Jewish calendar. This holiday commemorates many historical tragedies, most significantly the destruction of both Holy Temples in Jerusalem. One of the most common stories heard on Tisha b’Av is about Napoleon walking by a Paris synagogue on this day, hearing the lamentations and loud weeping of the Jews. In the story, he asks what the Jews are crying about, and after being told about the destruction of the Temple nearly two millennia ago, apparently remarks something along the lines of: “A nation that cries and fasts for 2,000 years for their land and Temple will surely be rewarded with their Temple.”

Hearing this story immediately sets off some alarms. Firstly, Napoleon was no ignoramus, and was certainly well aware of the destruction of the Temple (after all, the Temple is featured in the “New Testament” and plays an important role in Christian history as well). More notably, Napoleon was a military man his entire life; his biography is the very definition of a tough guy. This man lived by the sword—it is highly unlikely that he would praise people for sitting and crying about something.

In fact, the myth of Napoleon and Tisha b’Av has been debunked multiple times. One of the earliest known sources of the legend is a Yiddish article from 1912, later included in the 1924 American Jewish Yearbook, and similarly appearing in a 1942 book called Napoleon in Jewish Folklore. Here, we are given a far more logical version of the story: After hearing the weeping of the Jews in a synagogue in Vilnius, Napoleon points to his sword and says, “This is how to redeem Palestine.”

Napoleon and the Jews

An 1806 depiction of Napoleon emancipating the Jews

Napoleon would actually play a tremendous role in Jewish history, and might even be credited with starting the process of “redeeming Palestine”. It was Napoleon that ushered in the “emancipation” of Jews in Europe. Wherever he conquered, he would free the Jews from the ghettos, and give them equal rights. In France, he went so far as to declare Judaism one of the state’s official religions in 1807. Napoleon also famously sought (and failed) to re-establish the Sanhedrin.

These actions brought upon him the ire of many of his contemporaries, especially Czar Alexander of Russia, who branded Napoleon the “Anti-Christ” for liberating the despised Jews. Moscow’s religious authority at the time proclaimed:

In order to destroy the foundations of the Churches of Christendom, the Emperor of the French has invited into his capital all the Judaic synagogues and he furthermore intends to found a new Hebrew Sanhedrin—the same council that the Christian Bible states condemned to death (by crucifixion) the revered figure, Jesus of Nazareth.

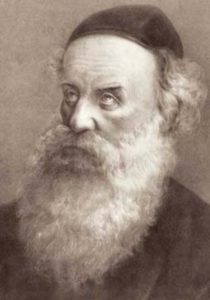

Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, the “Alter Rebbe” (1745-1812)

Of course, most Jews were ecstatic, and relished their newly acquired liberties. It became common for Jews to name their children “Napoleon”, or adopt the last name “Schöntheil”, the German translation of “Bonaparte”. Yet, not all Jews were happy about this development. The Alter Rebbe—founder of Chabad, who lived during the times of Napoleon—wrote the following in one of his letters:

If Bonaparte will be victorious, Jewish wealth will increase, and the prestige of the Jewish people will be raised; but their hearts will disintegrate and be distanced from their Father in Heaven. But if Alexander will be victorious, although Israel’s poverty will increase and their prestige will be lowered, their hearts will be joined, bound and unified with their Father in Heaven…

The Alter Rebbe thus fled from the approaching French forces, inspired his followers to do the same, and even supported the Russian military. He was right about Bonaparte. Napoleon had no interest whatsoever in seeing the Jews flourish as Jews, or practice their religion proudly. His intentions were clear: the complete assimilation of the Jews into European society. It was Napoleon that first permitted Jews to serve in the military, openly stating that “Once part of their youth will take its place in our armies, they will cease to have Jewish interests and sentiments; their interests and sentiments will be French.”

As it turned out, opening the doors for Jews to serve in the French military would lead to the proliferation of the Zionist movement, and the establishment of the State of Israel.

France and Israel

1899 Guth painting of Alfred Dreyfus for Vanity Fair

In 1894, Theodor Herzl was a young journalist working in Paris. He was covering the infamous “Dreyfus affair”, where a Jewish captain in the French military, Alfred Dreyfus, was wrongly accused of treason. During this time, Herzl witnessed the extreme anti-Semitism of the French firsthand. He realized that no matter how much the Jews assimilate, they would still never be accepted into European society, and reasoned that the Jews must have their own free state. Thus, it was a Jewish soldier in the French military—what Napoleon so dearly wanted—which catapulted the Zionist movement.

Interestingly, Napoleon himself seemed to have supported the notion of a Jewish state in Israel. In 1799, before he was emperor, and while besieging the city of Acre in Israel, Napoleon issued a proclamation inviting “all the Jews of Asia and Africa to gather under his flag in order to re-establish the ancient Jerusalem. He has already given arms to a great number, and their battalions threaten Aleppo.” Ultimately, the British defeated Napoleon’s forces, and the plan never materialized.

Nonetheless, Napoleon’s role in igniting the flames of Zionism cannot be overlooked. Zionism was primarily a secular movement, its most fervent supporters being assimilated European Jews who, like Herzl, were frustrated that they were still hated and unwanted in European society. This secularism was a direct result of Napoleon’s campaigns. Without his spearheading of the Jewish “emancipation”, it is doubtful that there would have ever been a Zionist movement to begin with.

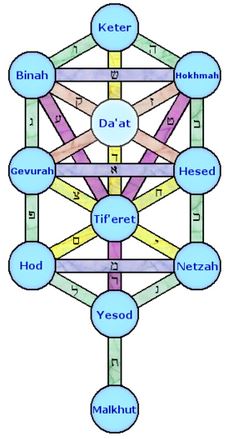

And although there is much to criticize about Zionism, these mostly secular European Jews succeeded in re-establishing a free Jewish state in the Holy Land after two very long millennia. Yes, the Israeli government is unfortunately secular, and Mashiach has not yet come, and there is a great deal of work to do to restore a proper Jewish kingdom as God intended. However, the State of Israel allowed for the majority of Jews to return to their homeland, escape persecution, live openly as Jews, fulfil mitzvot only possible in the Holy Land, and travel freely to Jerusalem. Israel is undoubtedly paving the way for the Final Redemption, which is why many great rabbis of recent times have described it as reshit tzmichat geulatenu, the first steps of the redemption.

It is therefore fitting that the gematria of “France” (צרפת), where the whole process began, is 770, a number very much associated with redemption as it is equivalent to בית משיח, the “House of Mashiach”. Ironically, this number is most special for Chabad—the same Chabad that so resisted Napoleon and the French! (And at the same time, adopted the tune of Napoleon’s military band as their own niggun, still known as “Napoleon’s March” and traditionally sung on Yom Kippur!)

Most beautifully, it appears to have all been predicted long ago by the Biblical prophet Ovadia, who prophesied (v. 17-21):

And Mount Zion shall be a refuge, and it shall be holy; and the house of Jacob shall possess their heritage… And they shall possess the Negev, the mount of Esau, and the Lowland, with the [land of the] Philistines; and they shall possess the field of Ephraim, and the field of Samaria; and Benjamin with Gilead. And the great exile of the children of Israel, that are wandering as far as צרפת [France], and the exile of Jerusalem that is in Sepharad, shall possess the cities of the Negev. And saviours shall come upon Mount Zion to judge the mount of Esau; and the kingdom shall be God’s.

The article above is an excerpt from Garments of Light: 70 Illuminating Essays on the Weekly Torah Portion and Holidays. Click here to get the book!