In this week’s parasha, Ki Tisa, we read how Moses goes up Mount Sinai on three separate occasions. His first ascent concludes with receiving the Two Tablets, only to come down and see the horror of the Golden Calf. Following this, the Torah tells us that “Moses returned to God”, back up the mountain, to address the Calf fiasco and its aftermath (Exodus 32:31). Moses then came back down to pitch a “Tent of Meeting” (33:7) where he could more regularly communicate with God without having to ascend the Mountain, and for when the Israelites would leave Sinai to head to Israel. Moses asked to see God’s Presence directly, and God replied that no mortal can see God and live, though He would show Moses His “back”. To do this, God asked Moses to come up Sinai one last time (34:2), where a new set of tablets would be created to replace the shattered ones.

When Moses descended from Sinai for the last time to present the new Tablets, the Torah tells us that “He was there with God for forty days and forty nights; he ate no bread and drank no water…” (34:28) Moses had gone up Sinai three times, each for forty days, making 120 days total. Indeed, if one counts the days of the Jewish calendar between Shavuot and Yom Kippur, one would find 120 days, since Shavuot is the date of the initial Sinai Revelation while Yom Kippur is when God forgave the Israelites for the Golden Calf and Moses returned with the new Tablets. At the end of Moses’ three sessions of intense meditation with God, his face glowed and the people could no longer look at him directly (34:29-30). Moses would henceforth wear a mask.

The Torah motif of going up a mountain to spend time in prayer and divine meditation spread all over the world, and we find very similar descriptions in other faiths that emerged after Judaism. Buddha, for instance, spent 40 days (or 49 days) up on a mountain meditating under a bodhi tree to attain enlightenment, and also abstained from food and water during that time. Jesus is said to have spent forty days in the wilderness without food and water, and Mohammad purportedly received his first revelation while meditating and fasting for days on Mount Hira at the age of 40. Despite the fact that Moses was undoubtedly the first, meditation today is associated more with Eastern faiths, and strangely not with Judaism.

The truth is that meditation has always been central to Judaism since ancient times. In fact, it is highly likely that it was Jewish exiles who introduced meditative practices around the world after their expulsion from Israel in the 6th century BCE at the hands of the Babylonians. It is intriguing to point out that many world religions began in the century following Israel’s exile, including Buddhism and Confucianism, as well as the Pythagorean and Orphic religions in Greece. Even ancient Zoroastrianism and Hinduism were heavily influenced by spreading Torah ideas in the middle of the first millennium BCE.

Today, science has uncovered the vast benefits of regular meditation—everything from reducing stress and improving sleep, to boosting the immune system and accelerating healing, even positively impacting the expression of our genes! So, what does the Torah tradition have to teach us about meditation, and what are some specific Jewish meditative techniques we can put into practice daily to enhance our lives?

Meditation in the Torah

The practice of meditation dates all the way back to Adam. After being banished from Eden, Adam spent enormous amounts of time in meditation, contemplation, and prayer to try to re-establish the connection with his Creator. He ultimately merited to receive communication from the angels Raziel and Raphael, who taught Adam numerous mystical secrets. Adam taught this divine information to his son Seth, and so on it passed down through the generations going all the way to Abraham. The Zohar (I, 55b) states that Abraham learned how to properly “contemplate” God from this information. The Torah tells us that Abraham’s son Isaac would “go out into the fields” to meditate (Genesis 24:63), while Jacob was known to do so particularly at night, as we see from his nocturnal visions of the Heavenly Ladder and his “wrestling” with an angel.

In Deuteronomy, Moses relayed the words of the Shema which instruct the entire Jewish people to meditate upon God’s Word “while sitting in your home and journeying on the way, and when you lie down and when you arise…” His successor Joshua told us that “This Torah should not cease from your lips, and you should meditate upon it day and night…” (Joshua 1:8) King David was perhaps the master meditator, as we see from countless verses in his Psalms. The Mishnah is the first ancient text to directly tell us that the earliest Jewish Sages would meditate for one hour before starting to pray (Berakhot 5:1). They were so deeply absorbed in their meditation that “even if a snake wrapped around their heel they would not cease.”

Of course, the bulk of discussion about meditation is found in Jewish mystical texts, starting from the most ancient sources like Sefer Yetzirah and the Heikhalot. The great Sephardic sages of the 12th and 13th centuries (including Avraham Abulafia and Azriel of Gerona) further refined and defined the art. By the time of the “golden age” of Kabbalah in 16th century Tzfat, Jewish meditation had become widespread and highly-developed. It later took on even greater significance in more modern mystical movements like Hasidism in Europe and in the circles inspired by the Rashash (Rabbi Shalom Sharabi, 1720-1777) in the Sephardi-Mizrachi world. Altogether, there are numerous Jewish meditative techniques with distinct methods and goals, including hitbodedut (“seclusion”), hitbonenut (“contemplation”), histaklut (“observation”), devekut (“attachment”), tzerufim (“combinations”), kavanot (“intentions”), and yichudim (“unifications”). These are in addition to the many Jewish prayers and recitations of berakhot, which themselves can be likened to meditative “mantras”.

Explaining each of the above forms of Jewish meditation is certainly beyond the scope of the present discussion. (For more on this, see the insightful works of Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, including his books Jewish Meditation, Meditation and the Bible, and Meditation and Kabbalah.) Here we shall focus on simpler meditations involving the recitation and/or visualization of particular words or verses, when done in the proper manner and in the right position and state of mind. To this we turn now.

Getting into a Meditative State

There are four major positions to be in while meditating: standing upright (such as during Amidah), sitting up with back straight, lying down horizontally, and a fetal position with head between the knees. The latter might seem strange but we actually find multiple figures in Tanakh and Talmud who would go into this position (for example, Eliyahu in I Kings 18:42). Kabbalistically, the knees correspond to the Sefirot of Netzach and Hod, which are the sources of prophecy. Thus, putting one’s head between the knees is a helpful conduit for attaining a more prophetic-like state. It also puts a person into an infant-like position of innocence and purity. Keep in mind the famous Talmudic teaching that, in a fashion similar to prophecy, a fetus is taught the entire Torah while in the womb, in its fetal position (Niddah 30b).

Having said that, the most common position for meditation is to be sitting down, in loose comfortable clothing, with back straight to facilitate proper breathing. Breathing is absolutely central to meditation, and deep rhythmic breaths are vital for success. Note that the Hebrew word for “soul”, neshamah, is nearly the same as “breath”, neshimah. Proper breath is required for tuning into the soul. Relatedly, the air around a person who is meditating should be as clean and fresh as possible. Some people like to light candles or incense to help them relax, but it is important to be aware that a flame will produce unhealthy smoke particles and poisonous carbon monoxide (albeit small amounts). It is best to have fresh, cool air, and even better to meditate outdoors in the woods, where the trees serve as natural air filters. The great Ramak (Rabbi Moshe Cordovero, 1522-1570) would go out into the wilderness to meditate in a technique called gerushin (“separation”) and recite various Torah verses to enter a prophetic-like state. His observations were recorded in Sefer HaGerushin.

Some people like listening to music to get into a calm, meditative state. This can certainly help, and we see in multiple places in Tanakh that music was used by the prophets (see, for instance, II Kings 3:15, and Zohar II, 45a). Eventually, a person might find the music to be a distraction, and absolute silence would be preferred. In the Tanakh we also find reference to groups of people prophesying together, and some may prefer meditating with a partner or in a group. One of the reasons for this is if a person manages to get into a very deep meditative state or trance, there will be someone around to help them come out of it.

Finally, one of the common concerns during meditation is the emergence of various thoughts and worries in one’s mind. A person might suddenly remember they have to do something important, or become engrossed in a pressing issue. It is totally alright for such thoughts to pop up, and there is no need to try to force them away. One can diverge from the meditation for several minutes and give the issue a little bit of thought, if necessary, then gently escort it away and continue in the meditation. This was already suggested long ago in Sefer Yetzirah, one of the most ancient Jewish mystical texts. It taught that when a person meditates upon the Ten Sefirot, they should “bridle their mouth” in silence, and if one’s thoughts “run” astray, they should simply “return” to the meditation—and this is the meaning of Ezekiel 1:14 who, in his prophetic vision, said ratzo va’shov, “run and return”!

Let’s conclude with a number of classic Jewish meditations, listed in order of duration, from one minute to over an hour. These will allow every individual to take up this important and highly-beneficial practice, even if they have only a minute a day to spare, and whether they are exploring meditation for the first time or are experienced mystics. Before beginning any of the following, it is vital to get into a relaxed and calm state of mind, in one of the comfortable positions described above. It is best to be in a state of joy, without sadness, for our Sages taught that the Shekhinah will not rest upon a person who is in a state of sadness (Shabbat 30b). It is also valuable to begin with a set of 18 deep, rhythmic breaths to get into the right mood (18 being חי and representing the breath of life).

Meditations for Everyone

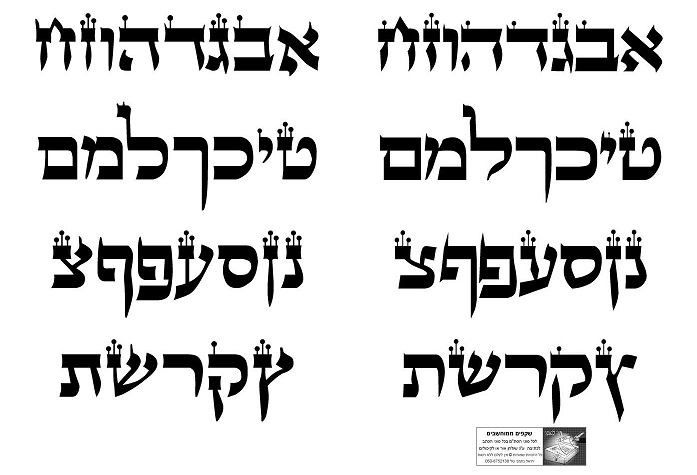

1 Minute: The simplest and most powerful one-minute-meditation is undoubtedly the Shema. (We are talking here about using the first verse of Shema as a meditation, outside of the twice-daily mitzvah of reciting the entire Shema. Also note that certain mystical texts describe Shema meditations that can last hours!) If ever Judaism had a “mantra”, it would be the Shema. It is the slogan and mission statement of the Jewish people. Each of the six words carries tremendous meaning, and can be visualized in the mind as it is recited. (It is best to visualize the letters in their proper shapes, as written in a kosher Torah scroll.)

There are four major kosher Torah fonts. Above on the left is Beit Yosef (used by most non-Hasidic Ashkenazis) and the one on the right is traditional Sefardi. The other two fonts are Arizal (left) and Chabad (right), below:

The first word Shema contains the three root sounds: an “a” which is open sound, a “m” which is a distinct tone, and a “sh” which is a cacophony. The “m” is considered a “clean” sound whereas the “sh” is a noisy sound, the sound of white noise on an untuned radio or television. (If someone is being noisy, we tell them to “sh!”) The Shema beings with all the noise of “sh”, progresses into a focused “m”, and ends with an open “a”. It is meant to get us away from all the “noise” around us in our lives and to focus on the oneness of God, and the oneness of the entire cosmos in which we find ourselves.

The final word echad is that oneness, and our Sages taught to meditate on it in the following manner: the aleph (1) represents the One God, and the chet (8) represents the Seven Heavens and the Earth, while the dalet stands for the four directions (or, on a more mystical level, the four universes of Asiyah, Beriah, Yetzirah, and Atzilut.) The idea is to focus intensely on the oneness of God and the fact that God permeates every iota of existence, throughout all the worlds and realms of Creation, including within us. Our Sages taught that one must “extend” the final dalet as they meditate deeply upon this. Note that the proper way to pronounce this letter is not a hard dalet but a soft dhalet (without a dagesh, as it is spelled in the Torah), which is like the “th” sound in that (but not like the “th” in three, which is a tav without a dagesh). If the dalet is pronounced hard (like many mistakenly do) it is impossible to extend it. With a soft d, on the other hand, it can easily be stretched out. You can hear it here:

5 Minutes: The human soul is composed of five levels: nefesh, ruach, neshamah, chayah, and yechidah. Each of these is associated with a different part of the body (see here). In this technique, one meditates upon each soul level for about one minute. Start with the nefesh, the lowest level of soul which is associated with the bloodstream, and sense it coursing through your veins. Then move on to ruach, associated with the vital organs, and especially the heart. Tune into your own heartbeat as you continue to breath deeply and rhythmically. The ruach is also connected to the lungs, so feel the expansion and contraction of your lungs as you breathe. Next comes the neshamah which sits in the brain and generates the mind. At this point one is able to be fully aware of their consciousness, their inner self and inner voice. Beyond this, the chayah is often associated with the aura that exudes from the body, while the yechidah is one’s direct connection to the Heavens above, like a spiritual umbilical cord. The chayah and yechidah levels are sometimes entirely ignored in mystical texts because they are much too esoteric and lofty. With enough practice, this type of meditation might lead a person into their subconscious and even unconscious mind.

10 Minutes: A 10-minute meditation is the right duration for meditating upon the Ten Sefirot. This is one of the most ancient Jewish meditations and opens Sefer Yetzirah (as mentioned above). A person can contemplate the features each of the Sefirot for a minute, or simply visualize their names. It can be done from the bottom up (Malkhut to Keter) or vice versa. Recall also that each of the Sefirot corresponds to a body part: the first three to the head and brain, Chessed and Gevurah to the right and left arm, Tiferet to the torso, Netzach and Hod to the legs, Yesod to the reproductive organ, and Malkhut to the feet.

15 Minutes: The letters of the divine Hebrew alphabet carry immense meaning. One powerful meditation is to visualize and contemplate each letter starting with aleph. A classic form of this meditation is to go up to the letter tzadi, which is the 18th letter. It can be done in 18 long breathes, or in shorter breaths spending roughly a minute per letter.

30 Minutes: A half-hour is an appropriate amount of time to cover all 32 Paths of Wisdom: the Ten Sefirot and the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet together.

1 Hour: A powerful meditation first described in the Zohar (II, 218b) is to contemplate in depth the Ketoret text outlining the recipe for the Temple incense. The Zohar states that one should visualize and meditate upon each and every word individually. The Zohar promises that one who can do this daily will (in addition to the other benefits of meditation) be spared from all illnesses, judgements, and negative energies. It is interesting to point out that in Temple times, the kohen gadol would take this incense with him into the Holy of Holies for his own meditative prayer, and it would help him enter a deeply prophetic state.

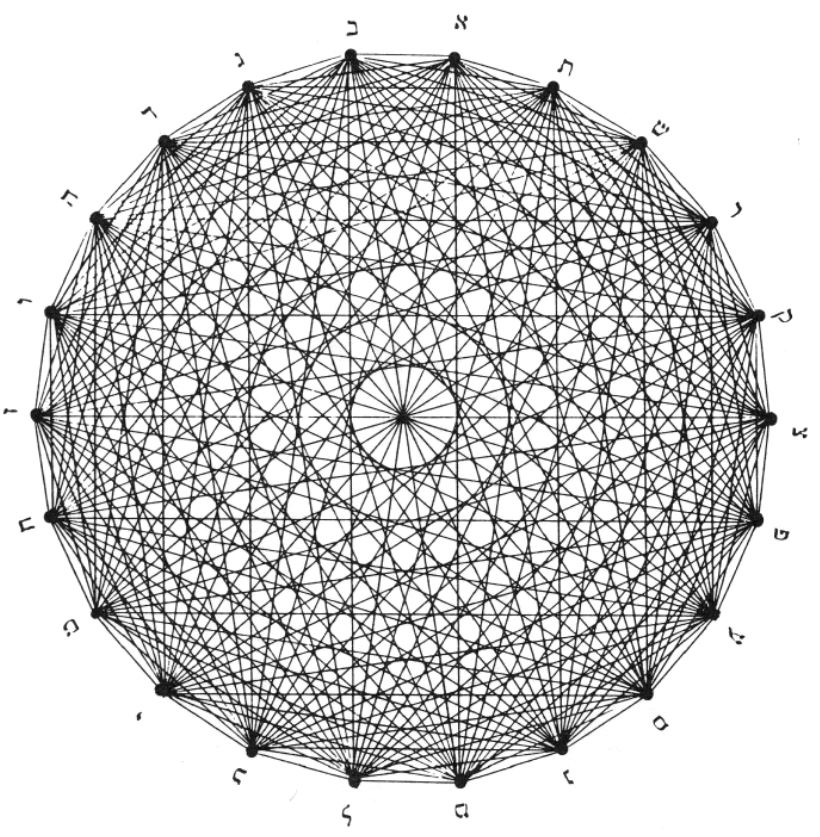

2+ Hours: The most intense meditation relayed in Sefer Yetzirah is to concentrate upon each of the 231 Gates, composed of all the possible two-letter combinations of Hebrew letters. So, one would start with aleph-beit, then aleph-gimel, aleph-dalet, and so forth before moving on to beit-gimel, beit-dalet, beit-hei, and then gimel-dalet, gimel-hei, gimel-vav, etc. concluding with shin-tav. (It may help to recite these sounds while they are visualized.) This meditation is quite difficult, and can take several hours or more to do properly. Despite its complexity and intensity, it is the foundation of Kabbalistic meditation and a key tool for attaining various mystical abilities.