Last week, we discussed the distinction between body and soul, and the need to develop each in its own way. The pure soul must be freed of the kelipot that encapsulate and suppress it, while the animalistic body must be refined and strengthened, both externally and internally. We are reminded of this again in this week’s parasha, Ekev, where Moses famously poses “What does Hashem, your God, ask of you?” The answer is to fear God, walk in His ways, to love Him, and to serve Him with all of one’s heart and soul, as well as to fulfill His mitzvot. We are then told to metaphorically “circumcise our hearts” (Deuteronomy 10:16). This, too, is an allusion to the kelipot, those spiritual “foreskins” that must be removed.

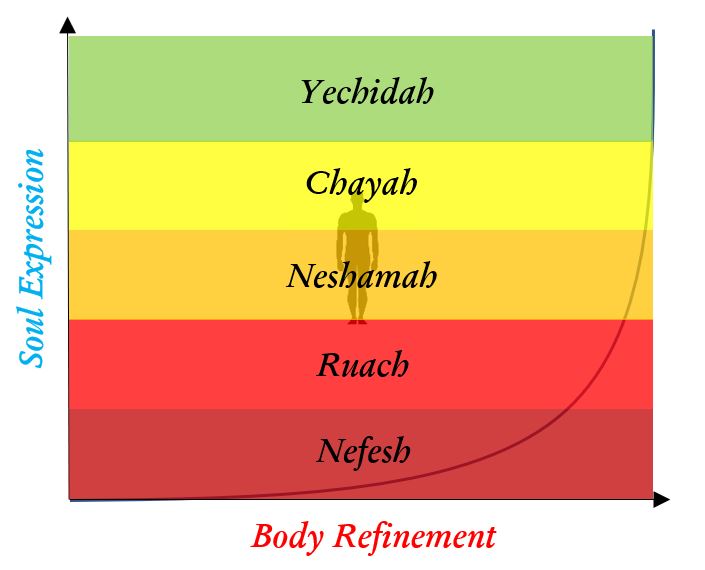

What we didn’t discuss last week is how exactly this process of refinement is accomplished. Aside from the general directive to fulfill mitzvot, what specifically needs to be done at each level of spiritual development? How does a person know whether they are in the “nefesh” stage, or the “ruach” stage? Should one focus on “neshamah”, or are they ready for “chayah”? This is what we will examine this week.

The nefesh is the lowest level of the soul, and one that is found (at least to some degree) within all living things. As the Torah tells us multiple times, the nefesh resides in the blood. As such, it is associated with the organ most closely tied to the maintenance of the blood. While one might think this organ is the heart, in reality the heart only circulates the blood; what actually processes blood is the liver. Fittingly, just as the nefesh is the lowest soul, the liver is anatomically the lowest vital organ, beneath the heart and lungs, and far beneath the brain. The liver, in Hebrew, is called kaved, sharing a root with kavod, “honour”. It is associated with the ego, and the constant need to be honoured and to receive.

In the realm of Sefirot, the nefesh corresponds to Malkhut, which is always described as an empty vessel. An unrefined person seeks to fill that emptiness through physical pleasures: food, drink, recreational substances, material goods. The need to be honoured, praised, showered with gifts and attention all comes from a weak nefesh. Of course, none of these things could ever truly fill the vessel, and are futile in bringing any kind of lasting satiation.

In the realm of Sefirot, the nefesh corresponds to Malkhut, which is always described as an empty vessel. An unrefined person seeks to fill that emptiness through physical pleasures: food, drink, recreational substances, material goods. The need to be honoured, praised, showered with gifts and attention all comes from a weak nefesh. Of course, none of these things could ever truly fill the vessel, and are futile in bringing any kind of lasting satiation.

The work of the nefesh, then, is to overcome the base animal instincts, and to rein in the negative qualities of pride, greed, and gluttony. (Related to this is anger, associated more specifically with the gallbladder that holds the liver’s bile.) Subduing the ego is the first step in the spiritual path. The Talmud (Sotah 5a) notes how there can be no Godliness whatsoever in the presence of a person with a big ego. Nor can there be any long-lasting growth for such a person. To begin growth and refinement, a person has to first recognize their deficiency, and that requires lowering the ego.

This is a key reason why Malkhut is referred to as shiflut, “lowliness”, to teach that the rectification for the nefesh stage is to bring down the ego, to develop one’s humility and modesty, and thereby slowly come to be in control of selfish animal desires. This is a huge task and, not surprisingly, the Torah has a plethora of mitzvot to address this rectification. These include all the dietary restrictions, and prohibitions against drunkenness and debauchery, as well as reciting prayers, blessings, confessions, and having a head covering—all of which serve to humble a person and remind them of their true position in the cosmos.

The Ruach Stage

The next level up is the ruach. This is associated with the heart and lungs, which circulate the air that one breathes. (Ruach literally means “air” or “wind”.) It corresponds to the six major middot, or qualities, of the heart: the Sefirot of Chessed, Gevurah, Tiferet, Netzach, Hod, and Yesod. As we are working our way from the bottom up, the first we encounter is Yesod, representing sexual purity. We find it in the expected position, right next to the level of nefesh which represents animalistic desires. Sexual intimacy is on the border between animal and human. Generally speaking, animals simply reproduce, and don’t have a notion of “intimacy” as humans do (with, perhaps, few exceptions like the dolphin). So, the sexual realm is not entirely nefesh, though it can certainly become very animalistic when abused.

The first step in the ruach stage, therefore, is to control the sexual urge. Again, the Torah has a great deal of mitzvot for this, including all the prohibited sexual relationships. In addition, there is the big mitzvah of lo tahmod and lo tita’ave, of not coveting or lusting after another’s spouse. The laws of niddah belong here as well, adding restrictions even within the context of a monogamous marriage to further strengthen one’s control over their libido.

Next up in the ruach level is Hod, which is about gratitude (lehodot is “to be grateful” or “to thank”). It is often translated as “acknowledgement”, the ability to recognize the value of others and respect them. Central to this, of course, is being able to recognize God’s role in our lives, and thank God for all that we are given. For this, too, there are many halakhot, including all the laws of reciting berakhot to thank God for just about everything, even after relieving one’s self in the bathroom, or witnessing great weather phenomena.

On the other side of Hod is Netzach, “victory”, which is about persistence and diligence. Overcoming laziness is a big one, especially in our day and age where most things have become so easy, and machines (or cheap labour) have made it unnecessary for people to exert much force of their own. Our Sages stated in many places how important it is to exert the body, especially for those whose work is docile, or for full-time scholars. Rabbi Yehuda and Rabbi Shimon, for instance, would carry large masses over their shoulders on the way to the study hall (Nedarim 49b). While doing so, the latter would recite: “Great is labour, for it honours its worker!” (For more on this, see ‘Why Physical Labour is a Spiritual Necessity’ in Garments of Light, Volume Two.) Faith is said to be rooted in Netzach, as well, for faith requires constant work and effort. There is an old Jewish saying that one can never stand in one place when it comes to spiritual matters; if a person is not moving forward, they are moving backwards. One who does little to maintain or grow their faith will inevitable slide “off the derekh”.

All of this naturally leads to the next aspect of ruach, which is Tiferet, “balance”. With Netzach taken care of, a person can have that ideal work-life balance. Only then can a person truly delve into the Torah, for the Torah is rooted in Tiferet, also called Emet, “Truth”. This helps to explain why Rabban Gamliel would say the Torah of a person who does not have work-life balance will be nullified (Avot 2:2). Within the realm of Tiferet is Torah-study and truth-seeking. Here a person will have attained a good balance between the physical and the spiritual. Tiferet sits directly above Yesod and Malkhut to indicate that, at this point, a person has officially overcome those lower desires, and balanced them in a near-perfect equilibrium.

For such a person, for instance, a fast day is not a chore or a bother, nor is there any great difficulty in getting through a couple of niddah weeks. Seeing an unusually attractive person on the street stimulates nothing but the desire to recite the berakhah of sh’kakha lo which our Sages instituted to thank God for His beautiful works. The central key to this ability is to be immersed in Torah, as our Sages stated that God created the yetzer hara, and He created the Torah as its tavlin, “antidote” (Sifre Devarim 45). However, true Torah immersion is only possible when the levels beneath Tiferet are established and rectified, for otherwise, as Rabban Gamliel warned, it is not real Torah at all.

Following directly from Tiferet is Gevurah, or Din, “self-restraint” and “judgement”. Here, a person is able to control their entire physical body. This is not just regarding the restraint of animal desires, but also the urge to, say, speak negatively or act rashly. True Gevurah is, as Ben Zoma taught, the ability to have total control over one’s inclinations (Avot 4:1). Ben Zoma cites Proverbs 16:32 as proof, where King Solomon says it is better to be forbearing and patient than to be a gibbor, and that a person who has total self-control is mightier than a great conqueror. Remember that we are still in the ruach stage of development, so it is fitting to point out that the term King Solomon uses for such a person is moshel b’rucho, someone who is in control of their ruach!

Together with this is the ability to judge others favourably, which is the positive aspect of Din. Only a person who is able to view others positively will be able to fully restrain themselves from disparaging them, whether directly to their face, or behind their back as lashon hara. This is one reason why Gevurah stands above Hod, for Hod was about acknowledging others and recognizing the good in them, and Gevurah is one step above that, in being able to judge others favourably at all times. At this point, a person is entirely pleasing to all others that they interact with, and will therefore be pleasing to God, too, as our Sages stated that “one with whom all others are pleased with, God is pleased with.” (Avot 3:10) Note again, how our Sages specifically use the term “ruach” here (כָּל שֶׁרוּחַ הַבְּרִיּוֹת נוֹחָה הֵימֶנּוּ, רוּחַ הַמָּקוֹם נוֹחָה הֵימֶנּוּ).

Finally, we have arrived at the last stage of ruach, which is Chessed, lovingkindness. Once again, we flow directly from Gevurah, for once a person is able to judge others favourably, they will be able to love others wholeheartedly. The difficult mitzvah of loving your fellow as yourself is rooted here in Chessed. To develop this ability, the Torah gives us many mitzvot about taking care of the poor, orphaned, and widowed; giving to charity, lending freely, standing up for each other, not harbouring hatred or revenge, and so on. At this level, a person is truly generous and loving, a paragon of kindness. There is no jealousy or envy in their heart whatsoever. Here in Chessed, too, is when all relationships with others are fully rectified. A person has complete shlom bayit, with peaceful and loving relationships among all members of their household, and even beyond to the extended family and community.

Neshamah, and Beyond

Past ruach is the neshamah stage. The seat of the neshamah is the brain, and it is therefore most-associated with the mind. It corresponds to the Sefirah of Binah, “understanding”. Here, at this point, a person can truly understand who they are and what their specific, personal rectifications are. There are fifty “gates” within Binah, corresponding to the fifty levels of constriction that Israel experienced in ancient Egypt. When they came out of Egypt, the Israelites had to spend fifty days preparing for the Sinai Revelation to break through those constrictions. (It is worth nothing that the Exodus out of Egypt is mentioned fifty times in the Torah!)

These fifty constrictions relate to various human fears and limitations. These include limitations of space, time, and money; anxieties, worries, and depressions, as well as the greatest fear of all—that of death. Within Binah is when a person sheds all those limitations and overcomes them. Our Sages state that Moses did exactly that, which is why the Torah says he died on Mount Nebo, where Nebo (נבו) is nun-bo, meaning he broke through all fifty (nun) limitations and grasped all fifty levels of understanding. At this point, a person is complete and fully rectified, from the conscious level, down through the sub- and unconscious.

The soul levels beyond are higher realms to be explored only by the few. Chayah corresponds to Chokhmah, “wisdom”, the divine code embedded within Creation. This is the ability to see God within all things; everything being only an extension of God’s emanation, Atzilut. Of this, the Alter Rebbe wrote in a letter to his nephew: “I no longer see a table, a chair, a lamp… only the letters of the Divine Utterances.” Higher still in the yechidah stage is absolute alignment with God’s Will, Keter. Here, every single action a person takes is in line with God’s Will. Such a person is both a divine emissary, and a completely free spirit.

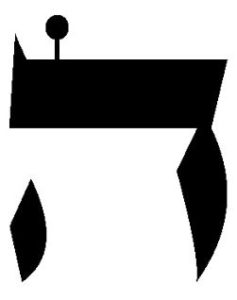

If the above appears complicated, there is a simpler framework of rectification: the level of nefesh is about rectifying one’s actions, the level of ruach is rectifying speech (tied directly to emotion), and the level of neshamah is rectifying one’s thoughts. These are the three modes of human expression and interaction. (They are represented by the letter hei, where the horizontal line is thought, the long vertical line is speech, and the short vertical line is action. The hei itself has a numerical value of five alluding to the five souls, expressed in this world though thought, speech, and action.) In other words, first a person must learn to act justly. The next level, more difficult, is refining one’s speech to be able to speak only words that carry a positive purpose. The highest level is purifying one’s mental faculties so that even one’s thoughts are entirely clean and holy.

If the above appears complicated, there is a simpler framework of rectification: the level of nefesh is about rectifying one’s actions, the level of ruach is rectifying speech (tied directly to emotion), and the level of neshamah is rectifying one’s thoughts. These are the three modes of human expression and interaction. (They are represented by the letter hei, where the horizontal line is thought, the long vertical line is speech, and the short vertical line is action. The hei itself has a numerical value of five alluding to the five souls, expressed in this world though thought, speech, and action.) In other words, first a person must learn to act justly. The next level, more difficult, is refining one’s speech to be able to speak only words that carry a positive purpose. The highest level is purifying one’s mental faculties so that even one’s thoughts are entirely clean and holy.

It is important to note that the processes above are not necessarily sequential. One can certainly work on developing different aspects of nefesh, ruach, and neshamah simultaneously. Some people need to work on certain qualities more than others. Of course, the above is also not a comprehensive list of everything there is to work on in the human process. It is to serve only as a general guide for the journey which we are all on. To tie it back to this week’s parasha, Moses asks what it is that God wants from us, and now we can see how the answer neatly corresponds to the five soul stages of development: “To be in awe of God [yechidah], to walk in all His ways [chayah], and to love Him [neshamah], and to serve Hashem, your God, with all of your heart [ruach] and all of your soul [nefesh].” (Deuteronomy 10:12)

וְעַתָּה֙ יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל מָ֚ה יְהֹוָ֣ה אֱלֹהֶ֔יךָ שֹׁאֵ֖ל מֵעִמָּ֑ךְ כִּ֣י אִם־לְ֠יִרְאָ֠ה אֶת־יְהֹוָ֨ה אֱלֹהֶ֜יךָ לָלֶ֤כֶת בְּכׇל־דְּרָכָיו֙ וּלְאַהֲבָ֣ה אֹת֔וֹ וְלַֽעֲבֹד֙ אֶת־יְהֹוָ֣ה אֱלֹהֶ֔יךָ בְּכׇל־לְבָבְךָ֖ וּבְכׇל־נַפְשֶֽׁךָ׃