In this week’s parasha, Vayishlach, we read about Jacob’s return to the Holy Land after twenty years in Charan. After some time, Jacob and the family make a stop in Beit El, where Jacob first encountered God decades earlier. God appears to Jacob once more, and promises that “the land which I gave to Abraham and to Isaac, I will give to you and to your seed after you” (Genesis 35:12). God makes it clear that the Holy Land is designated solely for the descendants of Jacob—not the descendants of Esau, and not the descendants of Ishmael, or any other of Abraham’s concubine sons. It is the land of Israel, the new name that Jacob receives in this week’s parasha.

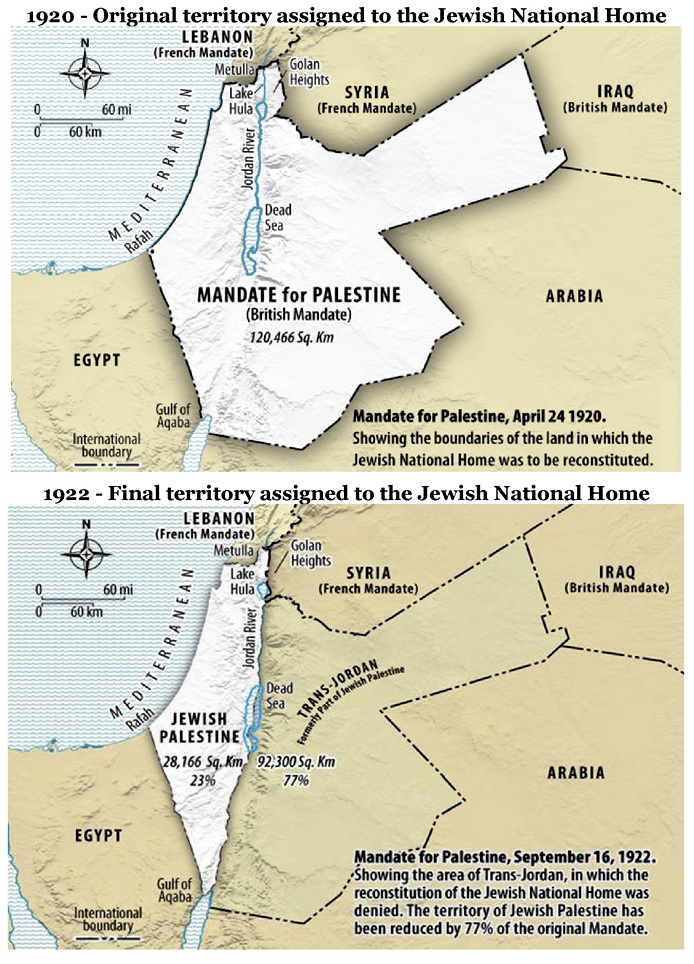

In fact, in this parasha we see mention of many Israelite sites, both ancient and modern, such as Hebron and Bethlehem. In our day, all of these are unfortunately within the political entity typically referred to as the “West Bank”. This title comes from the fact that the area is geographically on the west side of the Jordan River. Initially, the British Mandate for Palestine included both sides of the Jordan River, before the British gave the east to the Arabs to create the state of Jordan. This was the original “partition plan” for Palestine, with the eastern half meant to serve as the Arab state and the western half to become a Jewish one. Many have forgotten this important detail.

The current flags of the state of Jordan and the Palestinian movement. It is estimated that about half of Jordan’s current population of 9.5 million is Palestinian Arab.

Nonetheless, the unsuitable title of “West Bank” has stuck ever since. Some rightly avoid using the term in favour of the more appropriate “Judea and Samaria”. Truthfully, even this title is not entirely accurate, for the region is nothing less than the very heartland of Israel, the location of the vast majority of Biblical events, and the home of a plethora of Jewish holy sites. Among them is the tomb of Rachel, as we read in this week’s parasha (Genesis 35:16-20):

And they journeyed from Beit El, and there was still some distance to come to Ephrath, and Rachel gave birth, and her labor was difficult… So Rachel died, and she was buried on the road to Ephrath, which is Bethlehem. And Jacob erected a monument on her grave; that is the tombstone of Rachel until this day.

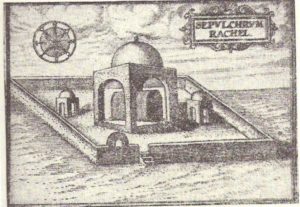

Throughout history, Rachel’s tomb was one of the most venerated sites in Judaism, and is often described as the Jewish people’s third-most holiest site (after the Temple Mount/Western Wall and Cave of the Patriarchs). As early as the 4th century CE the historian Eusebius already wrote of Rachel’s tomb being a holy site for Jews and Christians. Keep in mind that this is two centuries before anyone even whispered Islam. Not that it really matters, since Islam does not consider this a particularly special place. The Arab-Muslim historian and geographer of the 10th century, Al-Muqaddasi, doesn’t even mention Rachel’s tomb in his descriptions of Muslim-controlled Israel and its holy sites.

Meanwhile, the Jewish traveler and historian Benjamin of Tudela (1130-1173) describes Rachel’s tomb in detail as being a domed structure resting upon four pillars, with Jewish pilgrims regularly visiting and inscribing their names on the surrounding eleven stones (representing the Tribes of Israel, less the tribe of Benjamin, as Rachel died giving birth to him). The earliest Muslim connection to the tomb is in 1421, when Zosimos mentions a small mosque at the site. (“Zosimos the Bearded” was a Russian Orthodox deacon famous for proposing the Moscow-Third Rome principle—which may be of great significance for calculating the time of Mashiach’s coming, as we’ve written in the past.)

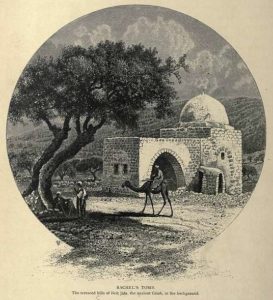

The Ottomans originally transferred ownership of the site to the Jewish community (in 1615) but later reneged on the promise and even built walls to prevent Jews from going there, according to the British priest and anthropologist Richard Pococke (1704-1765). Pococke writes that the Ottomans used the area as a cemetery. Nonetheless, Jews could not be kept away from their millennia-old holy site, and continue to make pilgrimages. Christian writers G. Fleming and W.F. Geddes note in their 1824 report that “the inner wall of the building and the sides of the tomb are covered with Hebrew names, inscribed by Jews.”

Six years later, the Ottomans officially recognized Rachel’s tomb as a Jewish holy site again, and ten years later the site was purchased by famous Sephardic Jewish financier and philanthropist Moses Montefiore. Montefiore rebuilt the crumbling tomb, and even constructed a small adjacent mosque to appease the local Muslims. Around this time, British writer Elizabeth Anne Finn, who lived in Jerusalem while her husband was the consul there, wrote that Jerusalem’s Sephardic Jews never left the Old City unless to pray at Rachel’s tomb. Similarly, the Missionary Society of Saint Paul the Apostle wrote in 1868 that Rachel’s tomb

has always been held in respect by the Jews and Christians, and even now the former go there every Thursday, to pray and read the old, old history of this mother of their race. When leaving Bethlehem for the fourth and last time, after we had passed the tomb of Rachel, on our way to Jerusalem, Father Luigi and I met a hundred or more Jews on their weekly visit to the venerated spot.

Later, Jewish businessman Nathan Straus (of Macy’s fame) purchased even more land around the site that Montefiore had purchased. (Interestingly, Montefiore’s own tomb in England is a replica of Rachel’s tomb.)

Under the British Mandate, Jewish groups applied on multiple occasions for permission to repair the site, but were denied because of Muslim opposition. The Muslims themselves didn’t bother repairing it, of course. Conversely, many of them were (and still are) happy to attack the site whenever an opportunity presents itself:

Throughout the 1800s, the local e-Ta’amreh Arab clan had blackmailed the Jews to pay up 30 pounds a year or else they would destroy the tomb. In 1995, Arabs—led by a Palestinian Authority governor—attacked Rachel’s tomb and tried to burn it down. In 2000, they laid a 41-day siege on the site during the Second Intifada. In light of this, it made total sense when UNESCO declared in 2015 that Rachel’s tomb is a Muslim holy site that is “an integral part of Palestine”. The laughable resolution only confirms the senselessness and irrelevance of the United Nations.

Had they bothered to look at the historical record, they would have seen that Rachel’s tomb is, was, and always will be a Jewish holy site of immeasurable significance. Countless Jewish pilgrims have experienced miracles there, particularly for health and fertility. According to tradition, Rachel is the only matriarch to be buried outside of the Cave of the Patriarchs so that her spirit can weep and pray for her children in exile. Her prayers are successful, for we are in the midst of the exile’s final end, as prophesied by Jeremiah (31:14-16):

Thus said Hashem: “A voice is heard in Ramah, in lamentation and bitter weeping.” It is Rachel, weeping for her children. She refuses to be comforted for her children, because they are not. Thus said Hashem: “Refrain your voice from weeping, and your eyes from tears, for your work shall be rewarded,” said Hashem. “And they shall return from enemy lands. And there is hope for your future,” said Hashem. “And the children shall return to their borders…”