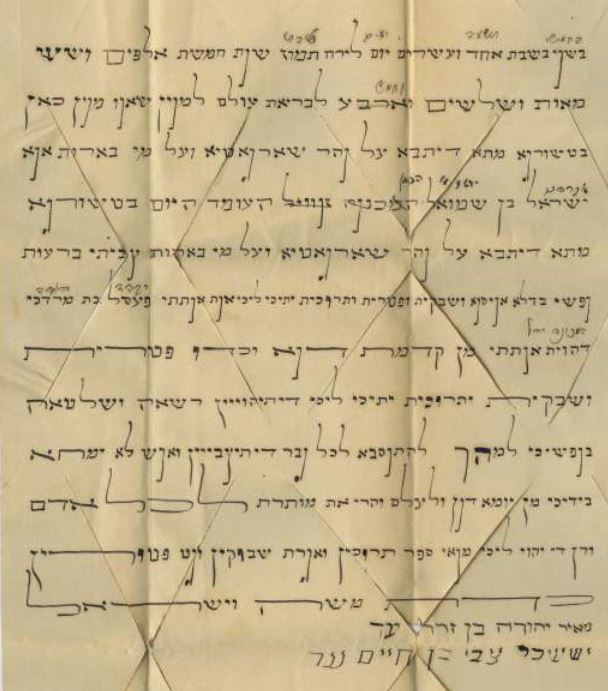

‘The Vision of the Valley of the Dry Bones’ by Gustav Doré

One of the fundamental principles of Jewish belief is in Techiyat haMetim, a future Resurrection of the Dead. The Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1138-1204) enumerated it among the 13 Principles of Faith that every Jew must believe in. He based it mainly on the famous Mishnah that opens the tenth chapter of the tractate Sanhedrin. It begins by stating that every member of the nation of Israel has a share in the World to Come, and then goes on to give several exceptions to the rule—those who forfeit their share. The first is anyone who holds “there is no Resurrection of the Dead from the Torah”. In other words, a person who argues that the Resurrection of the Dead is not a legitimate Torah principle. Such a person is a heretic and forfeits their share in the World to Come. The big question is: do we actually see anywhere in the Torah that there is a reference to the Resurrection of the Dead? The Talmud (starting on Sanhedrin 90b) gives numerous possibilities, most of them indirect derivations, before giving us one place in the Torah that does directly allude to the Resurrection of the Dead. This special verse is in this week’s parasha, Ha’azinu.

In the song of Ha’azinu, Moses quotes God as declaring: “See now that I, I am the One; There is no god beside Me. I deal death and give life; I wounded and I will heal: None can deliver from My hand.” (Deuteronomy 32:39) The order of words is significant: God did not say that He gives life and then puts to death, but rather that He puts to death and then He gives life! Thus, those that have died will be resurrected back to life. Some in the past disputed this interpretation, including the ancient Sadducees who did not believe in any afterlife. Recall that the Sadducees held strictly to the Law of Moses, to the Written Torah, and rejected the Oral Torah. They pointed to places in Tanakh that speak of She’ol, a repository for the lifeless dead, and quoted verses like “the dead do not praise God!” (Psalm 116:17) in support of their position. Interestingly, the Samaritans also believe only in the Torah, and reject even the Prophets and Ketuvim, yet they do believe in a Resurrection of the Dead based on our verse in Ha’azinu!

Once we look into the Prophets, we see numerous references of the future Resurrection. The first that is typically cited is Ezekiel’s Vision of the Dry Bones (Ezekiel 37). In this episode, God took Ezekiel to a valley and raised up skeletons, asking the prophet if they could come back to life. Ezekiel replied that only God knows such things, and God proceeded to bring the bones back to life. In Rabbinic tradition, it is believed that these revived skeletons were a segment of the Tribe of Ephraim. Back in Egypt, the Israelites desperately awaited their salvation, and many believed the time of Redemption had come and gone. They miscalculated by 30 years, and a group of Ephraimites decided to take matters into their own hands and flee. Unfortunately, they didn’t make it and ended up dying (or being killed) in the Wilderness. It was these Ephraimites that God resurrected before Ezekiel’s eyes. This description is found in multiple places in Midrash (such as Yalkut Shimoni I, 226), and in the Talmud (Sanhedrin 92b). The same page of Talmud does offer an opinion that the Vision of the Dry Bones might only be metaphorical, or that it doesn’t necessarily imply a literal future resurrection of all the dead. It could just be highlighting God’s power to revive the dead in general, or even just an allegory for the restoration of Israel after destruction and exile. The contradiction is resolved by saying both are true: the Vision had metaphorical meaning, but it was also literally true!

Another place in Tanakh that is a clear source for Resurrection is Daniel’s statement that “Many of those that sleep in the dust of the earth will awake, some to eternal life, others to reproaches, to everlasting abhorrence.” (Daniel 12:2) Similarly, Isaiah stated “Oh, let Your dead revive! Let corpses arise! Awake and shout for joy, you who dwell in the dust. For Your dew is like the dew on fresh growth; You make the land of the spirits come to life.” (Isaiah 26:19) Here, Isaiah refers to a “dew” of resurrection, and mystical texts have much to say about this dew. One of the early Kabbalistic works, Sefer haPeliyah, says that it is the same dew that was used to revive the Israelites when they briefly “died” from the overwhelming Sinai Revelation. The Talmud (Chagigah 12b) says God keeps this special dew locked up in the highest of the Seven Heavens, the realm of ‘Aravot, alongside His Throne and chief angels like Seraphim and Ofanim. Elsewhere, the Talmud (Ketubot 111b) reads the verse above not as “dew on fresh growth” but as “dew of light”, since the exact words are tal orot. What is this light? It is the light of Torah, and therefore “Anyone who engages with the light of Torah, the light of Torah will revive him; and anyone who does not engage with the light of Torah, the light of Torah will not revive him.”

The Talmud here continues to say that all the righteous dead will resurrect specifically from Jerusalem, since it says in Psalms 72:16 that they shall “blossom out of the city like the grass of the earth”—and the city is none other than Jerusalem. The Zohar (II, 28b) adds that the future resurrection will begin from the indestructible luz bone. This bone will absorb the dew and become like dough, from which God will reform the body. Is there such a non-decomposing bone in the human body? As explored in depth before, scientifically speaking there is no such bone, and “luz” may actually refer to other things. It may even refer to Jerusalem itself, based on Jacob’s Vision in Genesis 28 which says the original name of the place was Luz. So, resurrecting from “Luz” may just mean that everyone will resurrect in Jerusalem!

Intriguingly, Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan suggested that luz may be referring to DNA, and the Zohar might be saying that resurrection will be possible by taking a small remaining DNA sample and reviving from it the entire body. Today, scientists have indeed made major advances in DNA biotechnology, organ printing, and cloning that may make it possible. In fact, in another place the Zohar (I, 135a, Midrash haNe’elam) actually suggests this might be the case: “In the future time, the Holy One, blessed be He, will rejoice with the righteous, and will rest His Presence upon them, and all will rejoice with great joy… Said Rabbi Yehuda: the righteous are destined in that time to create worlds and resurrect the dead.” So, it will be the Tzadikim in the Messianic Age who will have the power to revive the dead! It remains to be seen whether this will be an entirely spiritual power, or whether it might involve the use of DNA technology.

Relatedly, advances in modern medicine and health are allowing us to dramatically increase lifespans. Isaiah prophesies that a time will come when a centenarian will be considered a “youth” (Isaiah 65:20). The ancient Book of Jubilees (Ch. 23) speaks of a time when man’s lifespan will return to that of Adam and the first generations, who lived nearly a millennium. In the future, each person will enjoy a thousand-year lifespan. This is probably related to the Talmudic and Midrashic statement that the Messianic Age will conclude by the year 6000, after which there will be a cosmic thousand-year Sabbath (see, for instance, Sanhedrin 97a). Based on Psalm 147:2-3, the Zohar (I, 139a, Midrash haNe’elam) gives a more detailed timeline: first Jerusalem will be rebuilt (arguably this has already happened), and then the Temple will be rebuilt, followed by the Ingathering of the Exiles, and only forty years after this will the Resurrection of the Dead begin.

Initially, all will be resurrected, including the wicked, except the pre-Flood generation (Yalkut Shimoni II, 429). Once everyone is resurrected, they will be judged and receive their due reward or punishment. This is also affirmed in the Talmud, in the famous discussion between Rabbi Yehuda haNasi and the Roman emperor Antoninus (Sanhedrin 91a-b). The latter questioned how God could judge a soul—which is pure and righteous—for the sins of the body, and how God could judge a body—which is just a hunk of matter and otherwise lifeless—for actions driven by the soul. Using a clever parable, Rabbi Yehuda explained how God will bring souls back into bodies and judge both together. (See also the Ramban in his Discourse on Rosh Hashanah, where he explains how Judgement Day will follow the Resurrection.)

The righteous will go on to enjoy their reward, as supported by another passage in Kiddushin 39b, which states the true reward for all mitzvot will be bestowed in the Era of Resurrection. This is the real definition of Olam HaBa, the “World to Come”, that our Sages speak of. While the term Olam HaBa is often used more ambiguously or in reference to other realms, it is really the era of reward here on Earth, when body and soul reunite. This is further supported by the Talmud in Ketubot 111b which says that in Olam HaBa, the yields of fruits and vegetables will multiple dramatically, and making wine will be effortless, with a single grape or cluster of grapes able to “produce no less than thirty jugs of wine”. This teaching is based on a verse in this week’s Ha’azinu, too.

Modern harvesting and winemaking technologies have already automated much of the process and simplified winemaking significantly, in fulfilment of Talmudic prophecy.

Another verse in this week’s parasha states that God’s Holy Land “atones for its people” (Deuteronomy 32:43). And so, there is a belief that those buried in the Holy Land have all their sins automatically wiped out. Rabbi Elazar takes it one step further and says only those buried in Israel will merit to be resurrected! The other Sages counter that this cannot be the case, and that anyone who at least “walked four cubits in the Land of Israel is assured a place in the World to Come”. However, we know that Resurrection can only take place in the Holy Land, so what will happen to all the bodies buried outside of Israel? God will miraculously make the corpses from all over the world “roll” through underground tunnels to Jerusalem! (Ketubot 111a)

The Talmud further tells us (both in Ketubot 111b and in Sanhedrin 90b) that people will be resurrected fully clothed. Rabbi Meir used a parable to explain this to Queen Cleopatra, saying that just as a “naked” kernel of wheat is buried in the ground and sprouts new wheat grains with several layers of chaff, so too will the righteous be resurrected covered up. Reish Lakish, meanwhile, uses two Scriptural verses to prove that people will initially be resurrected in the same state in which they died (blind, lame, etc.) but will then be miraculously healed. Since Adam and Eve were created as twenty-year-olds in the Garden of Eden (Beresheet Rabbah 14:7), it seems people will similarly take on the youthful bodies of a twenty-year-old.

The Zohar’s Midrash HaNe’elam cited above suggests that the process of Resurrection may last something like 200 years until all the righteous return. First will be revived the generation of the Exodus (Zohar III, 168b), along with the great Patriarchs and Prophets of old. Then all those who “drew water” from the wellsprings of Torah. Everyone else will follow, and all will eventually enjoy a millennium of peace and prosperity, with the ability to explore the farthest reaches of the universe and the highest heavens, and to truly marvel at all of God’s creations in the vast cosmos. It isn’t clear what will happen after that. Some envision a totally spiritual existence entirely devoid of the physical, perhaps for eternity (which is really hard to fathom). Others believe God will simply hit “reset” and a new Sabbatical cycle will begin, with civilization starting from the beginning all over again. Whatever the case, we must first usher in Mashiach and the Messianic Age, followed by the Era of Resurrection, and a millennium of Shabbat peace and reward. May we merit to see it soon.

Gmar chatima tova!

As we prepare to usher in a new year, we remember that while our calendar follows lunar months, it is still synchronized to the sun over the course of a 19-year cycle. Since a lunar month is 29.5 days, each month on the Hebrew calendar is either 29 or 30 days, resulting in a year that is typically just 354 days long. The solar year is a bit over 365 days long, meaning that a strictly lunar calendar will fall behind 11 days each year. To avoid this problem, we add an entire leap month, a second Adar, seven times in 19 years. This ensures that we stay in synch with both moon and sun. The upcoming year will be such a leap year, with 13 months instead of 12.

As we prepare to usher in a new year, we remember that while our calendar follows lunar months, it is still synchronized to the sun over the course of a 19-year cycle. Since a lunar month is 29.5 days, each month on the Hebrew calendar is either 29 or 30 days, resulting in a year that is typically just 354 days long. The solar year is a bit over 365 days long, meaning that a strictly lunar calendar will fall behind 11 days each year. To avoid this problem, we add an entire leap month, a second Adar, seven times in 19 years. This ensures that we stay in synch with both moon and sun. The upcoming year will be such a leap year, with 13 months instead of 12.