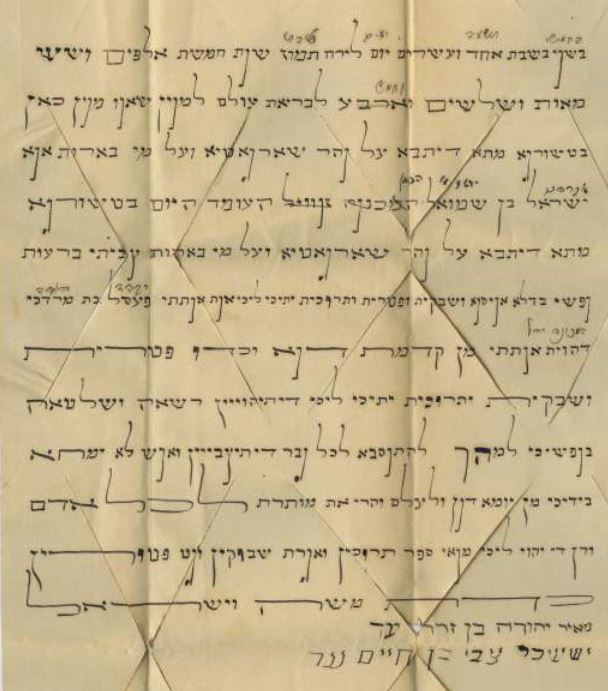

A get from the 19th-century (Credit: Israel Museum)

This week’s Torah portion, Ki Tetze, sets the record for most mitzvot in one parasha with a whopping 74 of them. One of these mitzvot is that of divorce: “When a man takes a woman and becomes her husband, and finds her displeasing because he finds something obnoxious about her, he shall write her a bill of divorce, hand it to her, and send her away from his house.” (Deuteronomy 24:1) The bill of divorce, called here a sefer kritut, would come to be more simply known as a get. In fact, there is an entire Talmudic tractate, Gittin, that explores all aspects of divorce and bills of divorce.

One of the questions discussed in this tractate is what does the Torah mean when it says the husband discovers something “obnoxious” about his wife? It is actually one of the more famous arguments between the ancient Jewish schools of Hillel and Shammai two thousand years ago. The more stringent Shammai believed that divorce was only permitted if the woman committed adultery or did something promiscuous (Gittin 9:10). Hillel believed divorce was allowed under any circumstances, for whatever reason the relationship was not working out. (Rabbi Akiva went even further and said a man could divorce even if he simply found another woman who is more attractive!)

More intriguingly, it is here in the tractate about divorce where we first come across the now-ubiquitous term tikkun olam, literally “repairing the world”. Today, many believe tikkun olam is a Hebrew term for social justice, but this is not accurate. What does “tikkun olam” actually mean? And why does it come from a tractate about, of all things, divorce?

Maintaining Order

In the fourth chapter of Gittin, the Mishnah and Talmud give many examples of things the Sages instituted mipnei tikkun ha’olam, “for the betterment of the world”. One of the first such things is that originally divorce documents needed to include essentially any name that the husband and wife went by. Rabban Gamliel, one of the last presidents of Israel before the Temple was destroyed in the 1st century CE, instituted that a get should list all names by which the husband and wife are commonly known. This was done mipnei tikkun ha’olam, and would ensure that the divorce is properly recognized in all places and by all people, even where the husband and wife might be known by other names.

Another example of tikkun olam is the prozbul, instituted by Rabban Gamliel’s grandfather, Hillel himself (Gittin 4:3). Recall that the Torah commands that all loans be paid back during Shemittah, the Sabbatical year, or otherwise be forgiven. A problem arose in that people were hesitant to lend money as the seventh year approached, since it was more likely that the borrowers would be unable to pay back the debt, putting the lender at an unfair loss. The reduction in available credit harmed the Judean economy. So, Hillel creatively came up with a prozbul that would sidestep the issue and allow the repayment of loans passed the Sabbatical year. The Talmud (Gittin 36b-37a) explains that “prozbul” came from a Greek term, meaning this decree was pro for both the bulei and the butei, the rich and the poor, benefitting all members of society.

We can now begin to understand the original meaning of the term “tikkun olam”. It was about adjusting Jewish law where necessary, within the framework of halakhah, for the betterment of society and to maintain peace and order. With time, tikkun olam took on a more mystical, cosmic meaning, too.

Rectifying the World

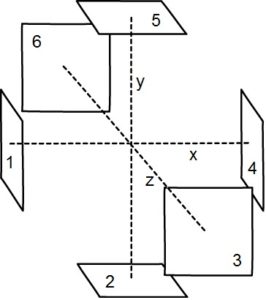

Ancient Jewish mystical texts described our world as one that is broken and in need of repair. God initially created a perfect world, but that world collapsed right at the beginning, in a process called shevirat hakelim, the “Shattering of the Vessels”. Adam and Eve had a chance to repair it, but only made the situation worse when they consumed the Forbidden Fruit. Since then, our mystical purpose is to reverse the damage and restore the wholesome primordial world, putting the pieces of those spiritual vessels back in place.

This process of repair and rectification, tikkun, is accomplished through the observance and fulfilment of mitzvot. This is the deeper purpose behind the Torah’s many laws—God gave them to us as tools to rectify the cosmos. Of all the mitzvot, the recitation of prayers and blessings in particular serve to elevate the world around us. All the small sparks of holiness, the nitzotzot, that came from the shattered vessels are trapped within the impure “husks”, kelipot, of the material world. The divine words of the prayers and blessings (in the original lashon hakodesh, the holy Hebrew tongue of Creation) are like spiritual formulas for freeing the sparks and restoring them to the Heavens. For instance, when one recites the boreh pri ha’etz blessing before consuming an apple, they unlock whatever sparks of holiness might be present inside. In this way, little by little, the entire cosmos is rectified.

The greatest proponent and expounder of this process was undoubtedly the Arizal (Rabbi Itzhak Luria, 1534-1572). It was he who put together the earlier Kabbalistic works into one complete mystical system, revealed only in the last two years of his short life in Tzfat, the “capital” of Jewish mysticism. The Arizal explained that this is the real reason why Jews were exiled to the farthest corners of the planet. On the surface level, it was a punishment and an exile, but God does not truly punish or exile. God is all-good, after all. The deeper reason for Jewish exile was so that Jews could reach every part of the planet and elevate all those lost sparks of holiness. Only when that process is complete will the Final Redemption be ushered in and the Messianic Age will officially begin.

Long before the Arizal, the Zohar already outlined the four aspects of tikkun. Recall that the Zohar is the central “textbook” of Kabbalah, first revealed to the public in the 13th century but originally dating back to the teachings of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai and his 2nd-century CE mystical circle. The Zohar (II, 215b) states that the first level of tikkun is rectification of the self. This is the process of personal development and self-refinement, the life-long journey of becoming a better, more Godly person. Each of us has many internal rectifications to achieve (both spiritual and physical).

Next is the tikkun of this lower physical world, primarily referring to that process of freeing the sparks trapped in the kelipot of the material around us. This is followed by the tikkun of the higher spiritual realms. For instance, reciting Kaddish for the departed serves to elevate their souls in the afterlife. Many of the mitzvot and rituals we perform similarly serve to affect great changes in the upper worlds. Finally, there is the tikkun of “God’s Name” which means a number of things, including bringing more Godliness down to Earth. Drawing more souls to recognize God, spreading Torah wisdom, and inspiring observance of mitzvot is a part of this process, too. The ultimate goal is, as the prophet Zechariah said, to bring about the day “When God will reign over the whole world; on that day God will be one and His name one.” (Zechariah 14:9)

These are the four aspects of genuine tikkun ha’olam: improving one’s self, fixing the spiritual fabric of the cosmos above and below, and infusing more Godliness into the world. So, how did some come to believe that tikkun olam is simply synonymous with “social justice”?

Tikkun as Social Justice

Real tikkun olam is clearly rooted in observance of Torah law and halakhah. With the rise of Reform Judaism in the 1800s, and their subsequent move away from halakhah, ancient ideas had to be rebranded. Tikkun olam was one of those ideas. Since Reform made halakhah essentially optional (at best), there was no way to root tikkun olam in the Law. Thus, rectifying the world was no longer a spiritual process requiring punctilious observance of mitzvot, prayers, and blessings, but rather a generic physical task of “making the world a better place”.

Now, there is certainly an element of “social justice” and making the world a better place within the larger umbrella of tikkun olam. It is true that God gave the Jewish people a mandate to improve the world, make it a more ethical and moral place, root out idolatry, spread monotheism, make life better for all, and be a “light unto the nations” (Isaiah 42:6). This is what the Jewish people were “chosen” for. Indeed, Jews have lived up to the challenge, and have been hugely instrumental (in disproportionate fashion) in advancing science and technology, medicine, civil law, democratic government, economics, arts, and yes, social justice, too. Some of the original “social justice warriors” of the past were Jews, including giants like Samuel Gompers and Louis Brandeis.

That said, tikkun olam must be rooted in the Torah. Commenting on the famous adage of Shimon haTzadik (in Pirkei Avot 1:2) that the world is established on “Torah, service, and acts of kindness”, the great codifier Rambam (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, 1138-1204) writes that true tikkun olam requires all three: Torah study, service of God, and kindness to others. Therefore, if some idea or movement is obviously contradictory to what the Torah stands for, it cannot in any way be “tikkun olam”. Today, some misuse the “tikkun olam” label and think it includes embracing all kinds of philosophies that are completely at odds with God and His Torah, which openly and proudly transgress Torah law.

For instance, while we should certainly care about the living conditions of all human beings around the world, there is no tikkun in marching alongside people who support terrorists that murder innocent Israelis. While we should certainly reach out to all Jews—regardless of their background, identification, or orientation—to inspire them to come closer to God and be more Torah observant, there is no tikkun in waving a rainbow flag nor in supporting “drag” shows. Nor is there any tikkun olam in going against the Torah’s gender roles, or in dismantling the traditional family unit, or in denying basic biological facts. Tikkun olam should not be confused with “spreading love” to anyone and everyone, or to embrace all peoples and philosophies and lifestyles. Tikkun olam cannot come before Torah law—it is supposed to enhance Torah law, not transgress it. Which brings us right back to our first question:

Why is tikkun olam introduced, of all places, in a tractate devoted to exploring divorce? I believe the subtle message is that we shouldn’t ever lose sight of what tikkun olam is truly about and that, sometimes, tikkun olam is not about embrace, but about divorce. There are things that must be opposed, and there are things that must be fought, and there is a line that cannot be crossed. We should never forget the true meaning of tikkun olam, that it is a spiritual process first and foremost, about bringing more Godliness and morality into the world (not Godlessness and immorality), about understanding the deeper cosmic purpose of Jewish laws and rituals, and about actually fulfilling those laws in order to bring about the Final Redemption, when true social justice (and not a distorted social justice) will reign.

May we merit to see that day very soon.